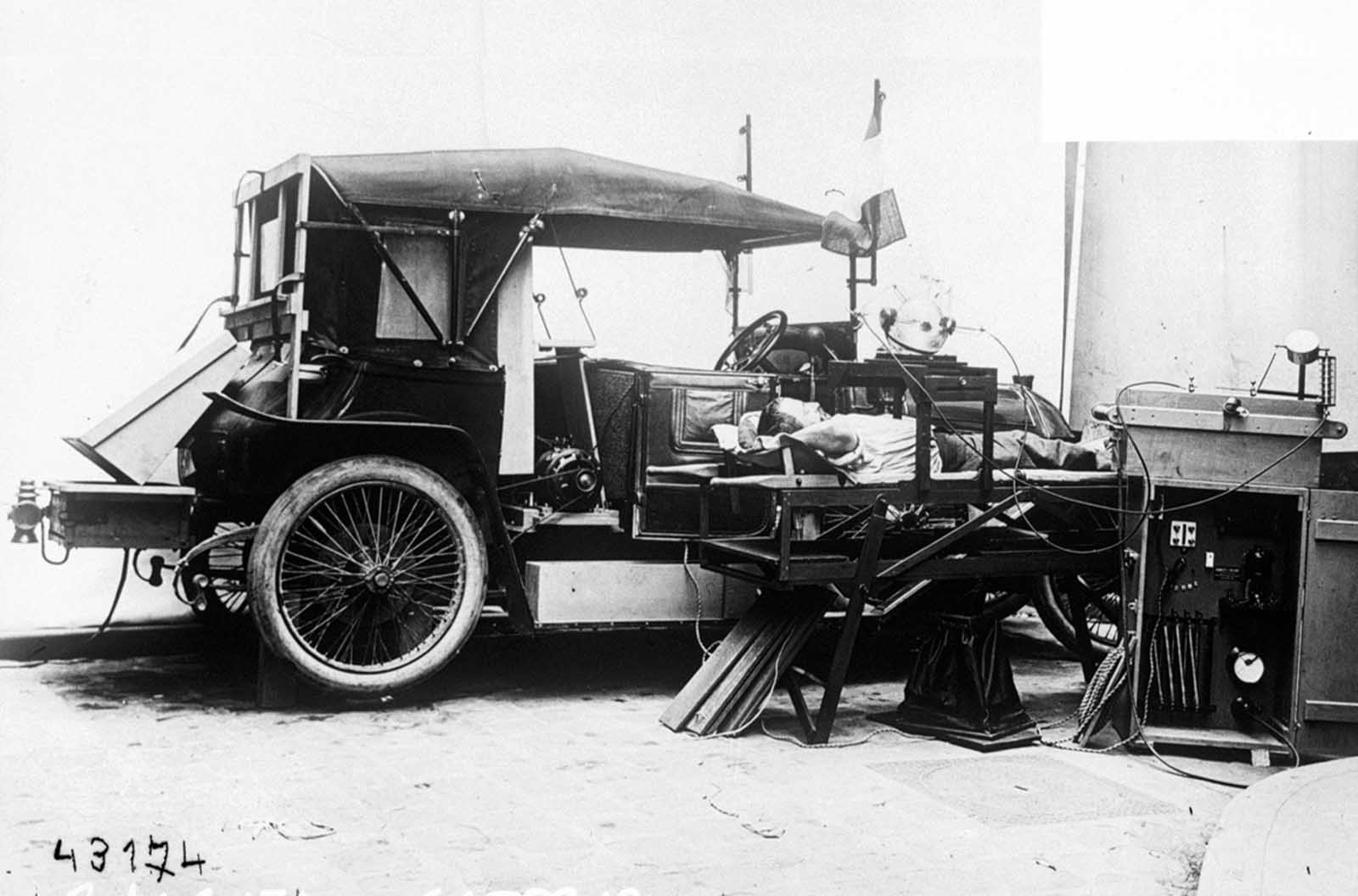

American troops using a newly-developed acoustic locator, mounted on a wheeled platform. The large horns amplified distant sounds, monitored through headphones worn by a crew member, who could direct the platform to move and pinpoint distant enemy aircraft. Development of passive acoustic location accelerated during World War I, later surpassed by the development of radar in the 1940s.

World War I was one of the defining events of the 20th century. From 1914 to 1918 conflict raged in much of the world and involved most of Europe, the United States, and much of the Middle East.

In terms of technological history, World War I is significant because it marked the debut of many new types of weapons and was the first major war to “benefit” from technological advances in radio, electrical power, and other technologies.

From the onset, those involved in the war were aware that technology would make a critical impact on the outcome. In 1915 British Admiral Jacky Fisher wrote, “The war is going to be won by inventions.”

New weapons, such as tanks, the zeppelin, poison gas, the airplane, the submarine, and the machine gun, increased casualties, and brought the war to civilian populations. The Germans shelled Paris with long-range (60 miles or 100 kilometers) guns; London was bombed from the air for the first time by zeppelins.

An Austrian armored train in Galicia, ca, 1915. Adding armor to trains dates back to the American Civil War, used as a way to safely move weapons and personnel through hostile territory.

World War I was also the first major war that was able to draw upon electrical technologies that had been in development at the turn of the century. Radio, for example, became essential for communications.

The most important advance in radio was the transmission of voice rather than code, something the electron tube, as oscillator and amplifier, made possible.

Electricity also made a huge impact on the war. Battleships, for example, might have electric signaling lamps, an electric helm indicator, electric fire alarms, remote control—from the bridge—of bulkhead doors, electrically controlled whistles, and remote reading of water level in the boilers.

Electric power turned guns and turrets and raised ammunition from the magazines up to the guns. Searchlights—both incandescent and carbon-arc—became vital for nighttime navigation, for long-range daytime signaling, and for illuminating enemy ships in night engagements.

Chemical warfare first appeared when the Germans used poison gas during a surprise attack in Flanders, Belgium, in 1915. At first, gas was just released from large cylinders and carried by the wind into nearby enemy lines. Later, phosgene and other gases were loaded into artillery shells and shot into enemy trenches.

The Germans used this weapon the most, realizing that enemy soldiers wearing gas masks did not fight as well. All sides used gas frequently by 1918. Its use was a frightening development that caused its victims a great deal of suffering, if not death.

The interior of an armored train car, Chaplino, Dnipropetrovs’ka oblast, Ukraine, in the spring of 1918. At least nine heavy machine guns are visible, as well as many ammunition cases.

Both sides used a variety of big guns on the western front, ranging from huge naval guns mounted on railroad cars to short-range trench mortars.

The result was a war in which soldiers near the front were seldom safe from artillery bombardment. The Germans used super–long-range artillery to shell Paris from almost eighty miles away. Artillery shell blasts created vast, cratered, moonlike landscapes where beautiful fields and woods had once stood.

Perhaps the most significant technological advance during World War I was the improvement of the machine gun, a weapon originally developed by an American, Hiram Maxim.

The Germans recognized its military potential and had large numbers ready to use in 1914. They also developed air-cooled machine guns for airplanes and improved those used on the ground, making them lighter and easier to move.

The weapon’s full potential was demonstrated on the Somme battlefield in July 1916 when German machine guns killed or wounded almost 60,000 British soldiers in only one day.

A German communications squad behind the Western front, setting up using a tandem bicycle power generator to power a light radio station in September of 1917.

Submarines also became potent weapons. Although they had been around for years, it was during WWI that they began fulfilling their potential as a major threat. Unrestricted submarine warfare, in which German submarines torpedoed ships without warning—even civilian ships belonging to non-combatant nations such as the United States—resulted in the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915, killing 1,195 people.

Finding ways to outfit ships to detect submarines became a major goal for the allies. Researchers determined that allied ships and submarines could be outfitted with sensitive microphones that could detect engine noise from enemy submarines.

These underwater microphones played an important part in combatting the submarine threat. The Allies also developed sonar, but it came too close to the end of the war to offer much help.

The firing stopped on November 11, 1918, but modern war technology had changed the course of civilization. Millions had been killed, gassed, maimed, or starved. Famine and disease continued to rage through central Europe, taking countless lives.

Because of rapid technological advances in every area, the nature of warfare had changed forever, affecting soldiers, airmen, sailors, and civilians alike.

Allied advance on Bapaume, France, ca. 1917. Two tanks are moving towards the left, followed by troops. In the foreground some soldiers are sitting and standing at the roadside. One of them appears to be having a drink. Beside the men is what appears to be a rough wooden cross with an Australian or New Zealand service hat on it. In the background other troops are advancing, moving field guns and mortars.

Soldier on a U.S. Harley-Davidson motorcycle, ca. 1918. During the last years of the war, the United States deployed more than 20,000 Indian and Harley-Davidson motorcycles overseas.

British Medium Mark A Whippet tanks advance past the body of a dead soldier, moving to an attack along a road near Achiet-le-Petit, France, on August 22, 1918. The Whippets were faster and lighter than previously deployed British heavy tanks.

A German soldier rubs down massive shells for the 38 cm SK L/45, or “Langer Max” rapid firing railroad gun, ca. 1918. The Langer Max was originally designed as a battleship weapon, later mounted to armored rail cars, one of many types of railroad artillery used by both sides during the war. The Langer Max could fire a 750 kg (1,650 lb) high explosive projectile up to 34,200 m (37,400 yd).

German infantrymen from Infanterie-Regiment Vogel von Falkenstein Nr.56 adopt a fighting pose in a communication trench somewhere on the the Western Front. Both soldiers are wearing gas masks and Stahlhelm helmets, with brow plate attachments called stirnpanzers. The stirnpanzer was a heavy steel plate used for additional protection for snipers and raiding parties in the trenches, where popping your head above ground for a look could be lethal move.

A British false tree, a type of disguised observation post used by both sides.

Turkish troops use a heliograph at Huj, near Aza City, in 1917. A heliograph is a wireless solar telegraph that signals by flashes of sunlight usually using Morse code, reflected by a mirror.

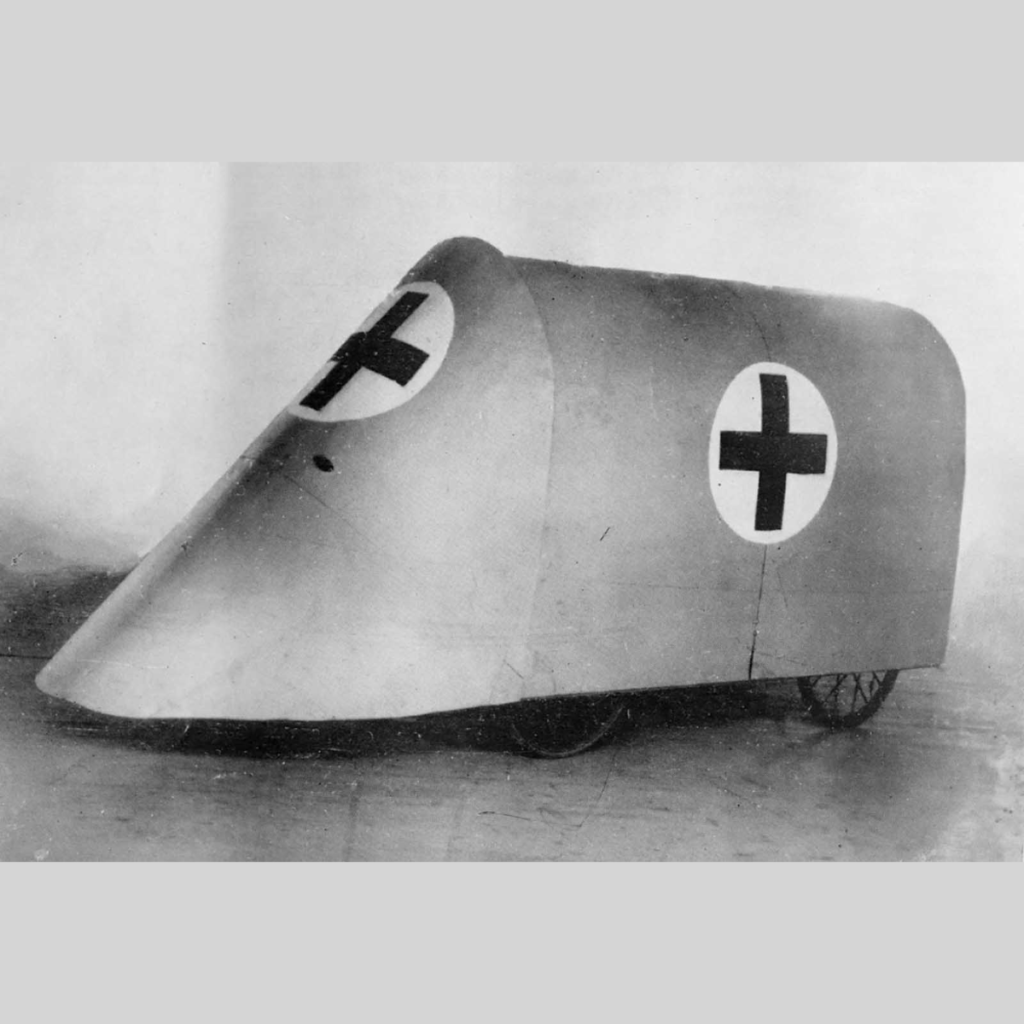

An experimental Red Cross vehicle designed to protect the wounded while gathering them from trenches during World War I, ca. 1915. The narrow wheels and low clearance would likely make this design ineffective in the chaotic and muddy front line landscape.

U.S. soldiers in trench putting on gas masks. Behind them, a signal rocket appears to be in mid-launch. When gas attacks were detected, alarms used included gongs and signal rockets.

A disused German trench-digging machine, January 8, 1918. The vast majority of the thousands of miles of trenches were dug by hand, but some had mechanical assistance.

A German soldier holds the handset of a field telephone to his head, as two others hold a spool of wire, presumably unspooling it as they head into the field.

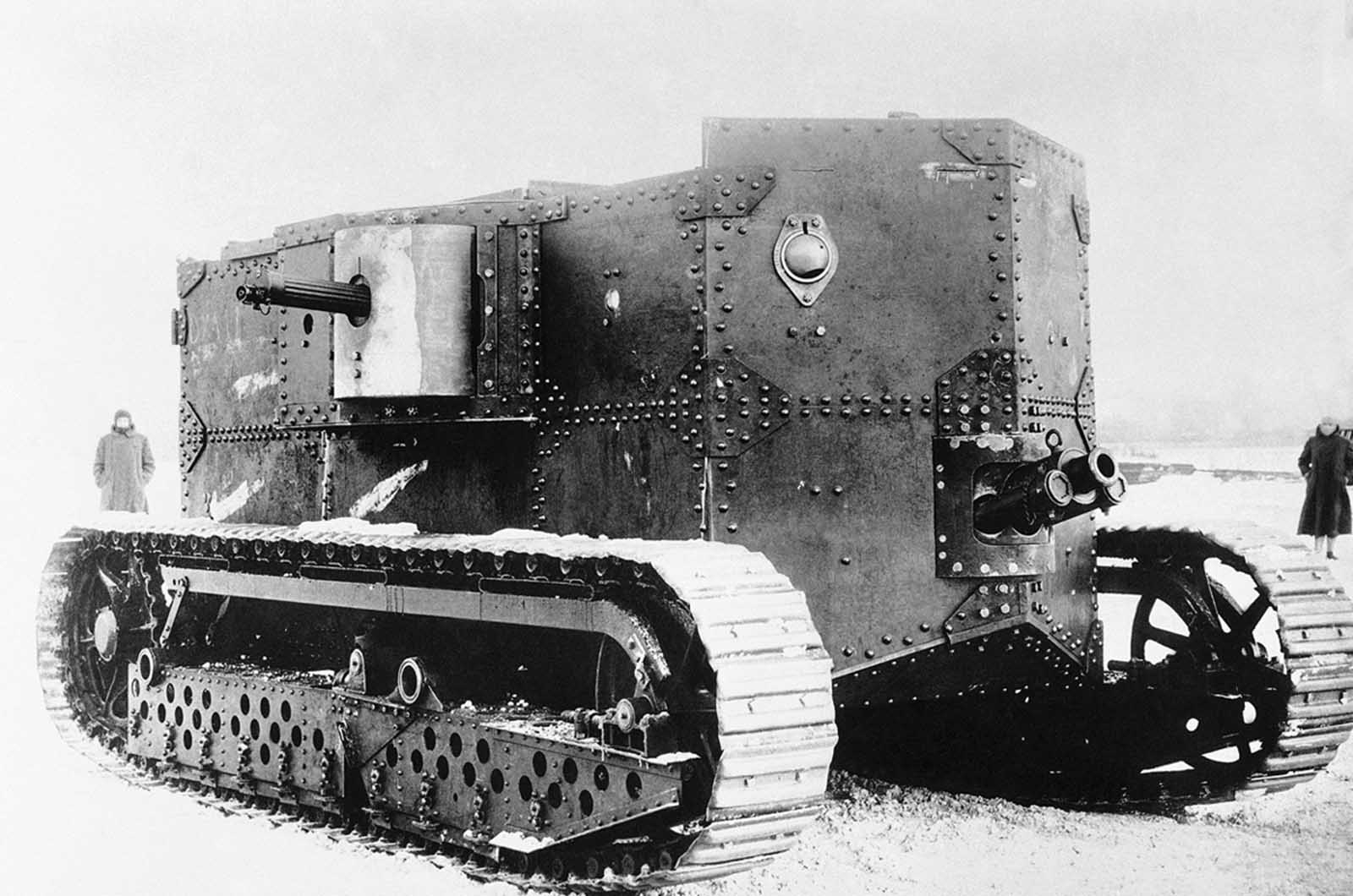

Western front, loading a German A7V tank onto a railroad flat car. Fewer than a hundred A7Vs were ever produced, the only tanks manufactured by Germany that they used in the war. German troops did manage to capture and make use of a number of allied tanks, however.

False horses, camouflage to allow snipers a place to hide in no-man’s land.

Women working in the welding Department of the Lincoln Motor Co., in Detroit, Michigan, ca. 1918.

A duel between tank and flamethrower, on the edge of a village, ca. 1918.

Derelict tanks lie strewn about a chaotic battlefield at Clapham Junction, Ypres, Belgium, ca. 1918.

Gas masks in use in Mesopotamia in 1918.

Americans setting up a French 37mm gun known as a “one-pounder” on the parapet of a second-line trench at Dieffmattch, Alsace, France, where their command, the 126th Infantry, was located, on June 26, 1918.

American troops aboard French-built Renault FT-17 tanks head for the front line in the Forest of Argonne, France, on September 26, 1918.

A German aviator’s suit is equipped with electrically heated face mask, vest, and fur boots. Open cockpit flight meant pilots had to endure sub-freezing conditions.

British Mark I tank, apparently painted in camouflage, flanked by infantry soldiers, mules and horses.

A Turkish artillery squad at Harcira, in 1917. Turkish troops with a German 105 mm light field howitzer M98/09.

Irish Guards line up for a gas mask drill on the Somme, in September of 1916.

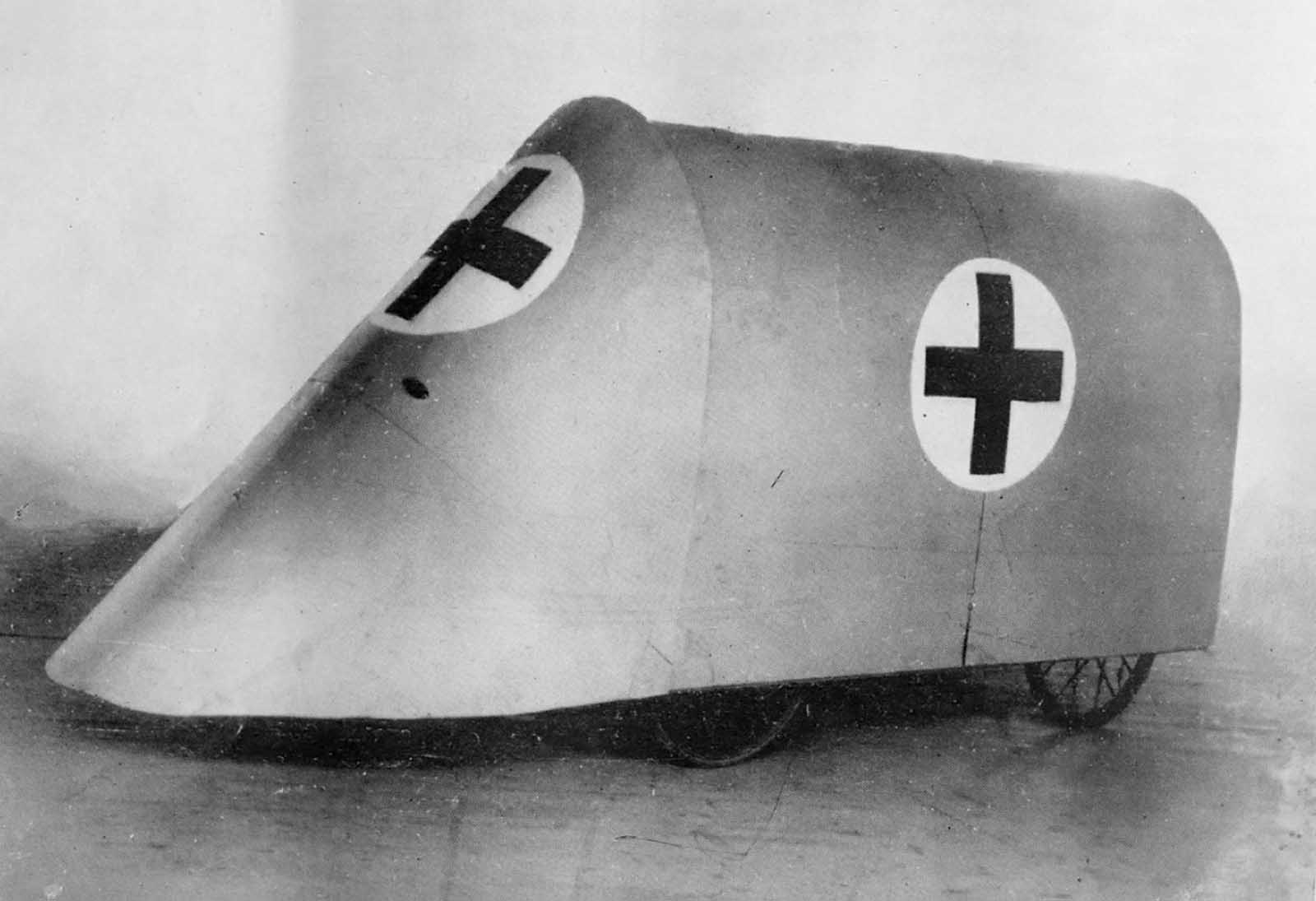

The Holt gas-electric tank, the first American tank, in 1917. The Holt did not get beyond the prototype stage, proving too heavy and inefficient in design.

On the site where a steel bridge was destroyed, a wooden temporary bridge has been built in place. Note that an English tank which fell in the river when the former bridge was demolished now serves as part of the foundation for the new bridge over the Scheldt at Masnieres.

Telegraph office, Room 15, Elysee Palace Hotel, Paris, France, Major R.P. Wheat in charge. September 4, 1918.

German officers with an armored car, Ukraine, Spring of 1918.

An unidentified member of the 69th Australian Squadron, later designated No. 3 Australian Flying Corps, fixes incendiary bombs to an R.E.8 aircraft at the AFC airfield north west of Arras. The entire squadron was operating from Savy (near Arras) on October 22, 1917, having arrived there on September 9, after crossing the channel from the UK.

Seven or eight machine-gun crews are ready to set out on a sortie in France, ca. 1918. Each crew consists of two men, the driver on a motorbike and the gunner sitting in an armored sidecar.

New Zealand troops and the tank “Jumping Jennie” in a trench at Gommecourt Wood, France, on August 10, 1918.

A German column looks over a destroyed Canadian Armored Autocar, the bodies of Canadian soldiers, empty belts, and cartridge boxes strewn about.

U.S. Soldiers in training, about to enter a tear gas trench at Camp Dix, New Jersey, ca. 1918.

German troops load gas projectors. Attempting to exploit a loophole in international laws against the uses of gas in warfare, some German officials noted that only gas projectiles appeared to be specifically banned, and that no prohibition could be found against simply releasing deadly chemical weapons and allowing th wind to carry it to the enemy.

Flanders front. Gas attack, September, 1917.

French lookouts posted in a barbed-wire-covered trench. The use of barbed wire in warfare was recent, having only been used for the first time in limited form during the Spanish-American War. All sides in World War I used extensive networks of barbed wire entanglements to prevent ground troops from moving forward. The effectiveness of the wire drove the development of technologies like the tank, and wire-cutting explosive shells set to detonate the instant they made contact with a wire.

American and French photographic staff, France, 1917.

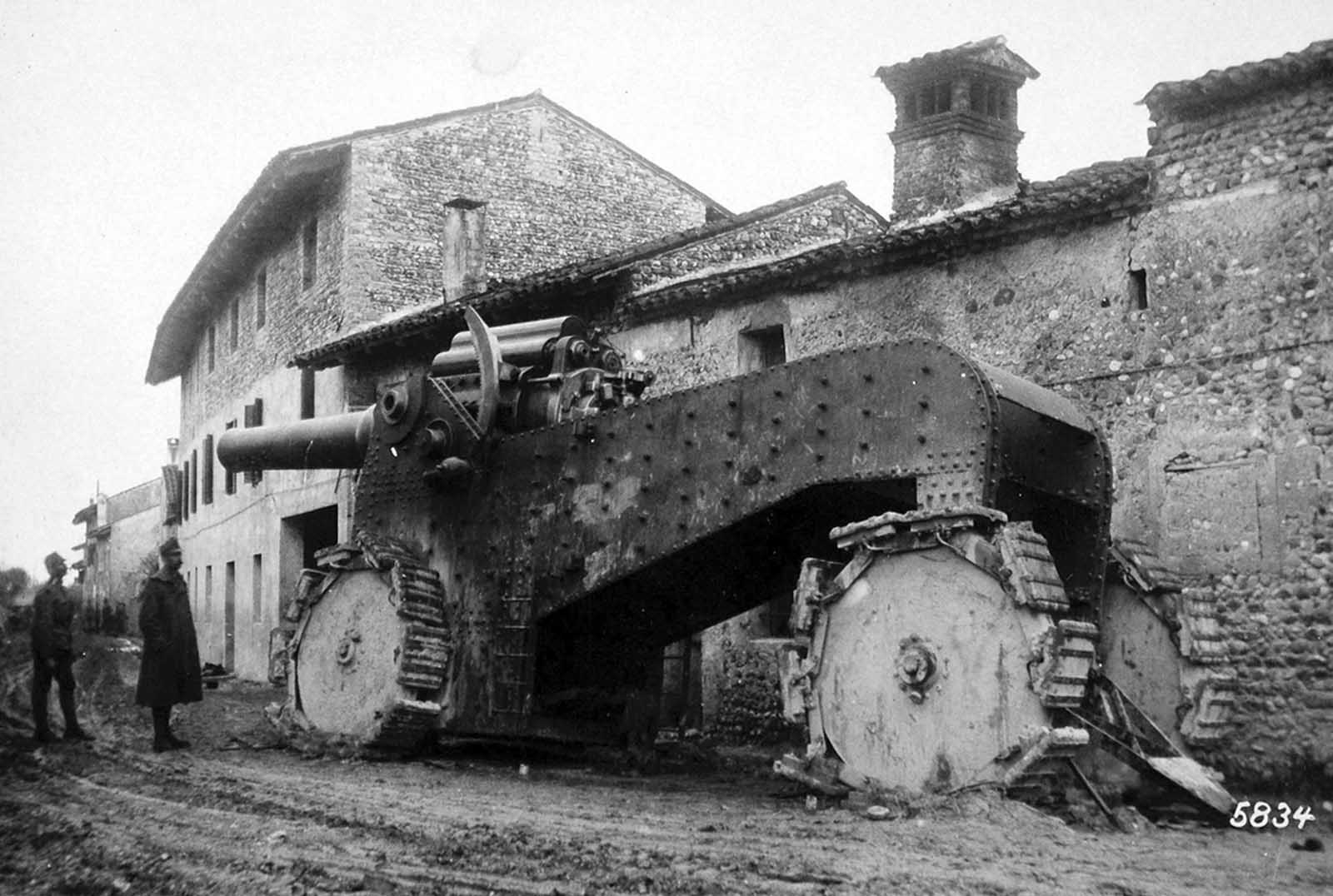

The original caption reads: “The Italian collapse in Venezia. The heedless flight of the Italians to the Tagliamento. Captured heavy and gigantic cannon in a village behind Udine. November 1917”. Pictured is an Obice da 305/17, a huge Italian howitzer, one of fewer than 50 produced during the war.

Western front, Flammenwerfers (flame throwers) in use.

A patient is examined in a mobile radiology lab, belonging to the French Army, ca. 1914.

A British-made Mark IV tank, captured and re-painted by Germans, now abandoned in a small wood.