Altamira, cave in northern Spain famous for its magnificent prehistoric paintings and engravings. It is situated 19 miles (30 km) west of the port city of Santander, in Cantabria provincia. Altamira was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1985.

The cave, discovered by a hunter in 1868, was visited in 1876 by Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, a local nobleman. He returned in 1879 to excavate the floor of the cave’s entrance chamber, unearthing animal bones and stone tools. On one visit in the late summer, he was accompanied by his eight-year-old daughter, Maria, who first noticed the paintings of bison on the ceiling of a side chamber. Convinced of the antiquity of the paintings and the objects, Sanz de Sautuola published descriptions of his finds in 1880. Most prehistorians of the time, however, dismissed the paintings as modern forgeries, and it was not until the end of the 19th century that they were accepted as genuine.

The Altamira cave is 971 feet (296 metres) long. In the vestibule numerous archaeological remains from two main Paleolithic occupations—the Solutrean (about 21,000 to 17,000 years ago) and the Magdalenian (about 17,000 to 11,000 years ago)—were found. Included among these remains were some engraved animal shoulder blades, one of which has been directly dated by radiocarbon to 14,480 years ago. The lateral chamber, which contains most of the paintings, measures about 60 by 30 feet (18 by 9 metres), the height of the vault varying from 3.8 to 8.7 feet (1.2 to 2.7 metres); the artists working there were thus usually crouched and working above their heads, never seeing the whole ceiling at once. The roof of the chamber is covered with paintings and engravings, often in combination—for example, the bison figures that dominate were first engraved and then painted. These images were executed in a vivid bichrome of red and black, and some also have violet tones. Other featured animals include horses and a doe (8.2 feet [2.5 metres] long, the biggest figure on the ceiling), as well as other creatures rendered in a simpler style. Numerous additional engravings in this chamber include eight anthropomorphic figures, some handprints, and hand stencils. The other galleries of the cave contain a variety of black-painted and engraved figures. In many cases the creator of the images exploited the natural contours of the rock surface to add a three-dimensional quality to the work.

The black paint used in the drawings was determined to be composed largely of charcoal, which can be radiocarbon dated. By the turn of the 21st century, this method had been applied to several images on the Altamira ceiling. Scientists now believe the ceiling paintings date from c. 14,820 to 13,130 years ago. In July 2001 an exact facsimile of the cave’s decorated chamber, entrance chamber, and long-collapsed mouth was opened to the public at the site.

Cave art, generally, the numerous paintings and engravings found in caves and shelters dating back to the Ice Age (Upper Paleolithic), roughly between 40,000 and 14,000 years ago. See also rock art.

The first painted cave acknowledged as being Paleolithic, meaning from the Stone Age, was Altamira in Spain. The art discovered there was deemed by experts to be the work of modern humans (Homo sapiens). Most examples of cave art have been found in France and in Spain, but a few are also known in Portugal, England, Italy, Romania, Germany, Russia, and Indonesia. The total number of known decorated sites is about 400.

Most cave art consists of paintings made with either red or black pigment. The reds were made with iron oxides (hematite), whereas manganese dioxide and charcoal were used for the blacks. Sculptures have been discovered as well, such as the clay statues of bison in the Tuc d’Audoubert cave in 1912 and a statue of a bear in the Montespan cave in 1923, both located in the French Pyrenees. Carved walls were discovered in the shelters of Roc-aux-Sorciers (1950) in Vienne and of Cap Blanc (1909) in Dordogne. Engravings were made with fingers on soft walls or with flint tools on hard surfaces in a number of other caves and shelters.

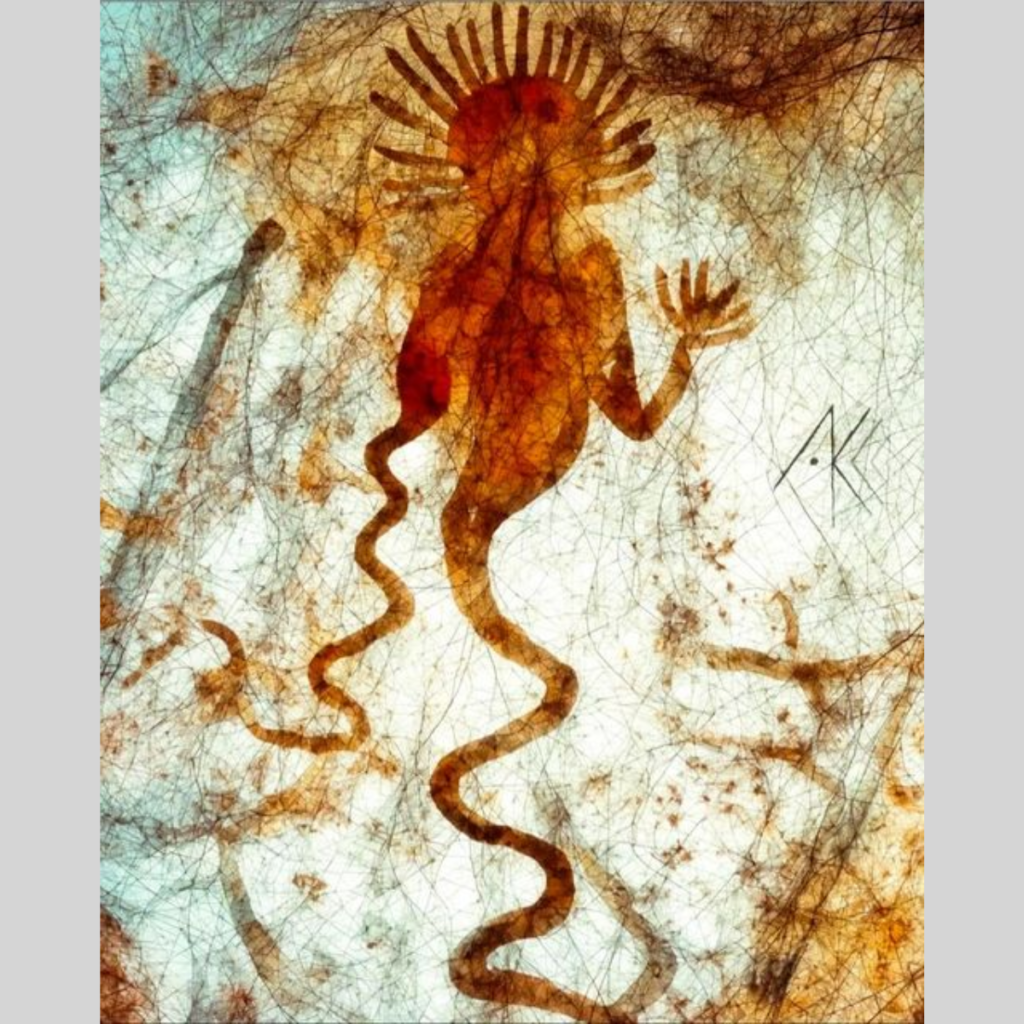

Representations in caves, painted or otherwise, include few humans, but sometimes human heads or genitalia appear in isolation. Hand stencils and handprints are characteristic of the earlier periods, as in the Gargas cave in the French Pyrenees. Animal figures always constitute the majority of images in caves from all periods. During the earliest millennia when cave art was first being made, the species most often represented, as in the Chauvet–Pont-d’Arc cave in France, were the most-formidable ones, now long extinct—cave lions, mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, cave bears. Later on, horses, bison, aurochs, cervids, and ibex became prevalent, as in the Lascaux and Niaux caves. Birds and fish were rarely depicted. Geometric signs are always numerous, though the specific types vary based on the time period in which the cave was painted and the cave’s location.

Cave art is generally considered to have a symbolic or religious function, sometimes both. The exact meanings of the images remain unknown, but some experts think they may have been created within the framework of shamanic beliefs and practices. One such practice involved going into a deep cave for a ceremony during which a shaman would enter a trance state and send his or her soul into the otherworld to make contact with the spirits and try to obtain their benevolence.

Examples of paintings and engravings in deep caves—i.e., existing completely in the dark—are rare outside Europe, but they do exist in the Americas (e.g., the Maya caves in Mexico, the so-called mud-glyph caves in the southeastern United States), in Australia (Koonalda Cave, South Australia), and in Asia (the Kalimantan caves in Borneo, Indonesia, with many hand stencils). Art in the open, on shelters or on rocks, is extremely abundant all over the world and generally belongs to much later times.