Nancy Burson arrived at the scene in 1948 St. Louis to take part in the rise of new media art and the technological advancements that made it possible. Burson, an American artist, writer and photographer, would come to be known for pioneering morphing technology and her Human Race Machine.

Burson’s involvement in the arts date back to her years as a student in Denver, at Colorado’s Women’s College (MoCP). There, she completed her studies in painting before moving to New York City in 1968 to begin her career. That same year, her visit to the MoMA exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age sparked her interest in the relationships between people and their mechanical counterparts. This fascination with the machine would become the driving force in her career (Seeing).

Initially, however, Burson’s interest was in understanding perception through her paintings and drawings; testing the concept that ‘seeing is believing’ (Seeing). A decade later, she quickly transitioned to testing the theory on film rather than canvas, and shifted her focus to the human face. The camera became her weapon of choice from that point on, and the face would continue to serve as her subject.

Still fascinated by the human vs. the machine, Burson was also making progress with an earlier concept she had devised. She envisioned a machine that would allow participants to watch themselves age. “I remember the exact moment I got the idea… I thought, ‘How great it would be if people could walk into a gallery and see how they would look in 20 or 50 years’ ” (Calio). It would require a computer program that could recognize, read and interact with a digital image. As Lev Manovich puts it, it would do so by turning a particular type of media into digital data that would be controlled by software. “This allows automating many media operations, to generate multiple versions of the same object”(Manovich, 17), a defining quality of new media, and if successful, a breakthrough in digital technology . Together with Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), MIT’s Media Lab, and various contributing scientists along the way, Burson made this imagined program a reality, creating the first computer program to be able to interact digitally with an image. It works by first mapping an image, then selecting a compatible image from a database to overlay the first, and so on, creating a digital composite (Calio).

In 1981, Burson patented the morphing technology after what Janet Murray would define, according to Inventing the Medium, as a necessary collaboration between the humanists and the scientists; a relationship that is the catalyst in advancing new media like Burson’s morphing technology. “The two traditions come together most energetically in collaborations focused on new structures of learning in which exploration of the computer is motivated by a desire to foster the exploratory process of the mind itself” (Murray, 5). Burson’s relationship with her collaborator, David Kremlich, eventually grew beyond the art and technology that brought them together, and he became her husband shortly thereafter (MoCP).

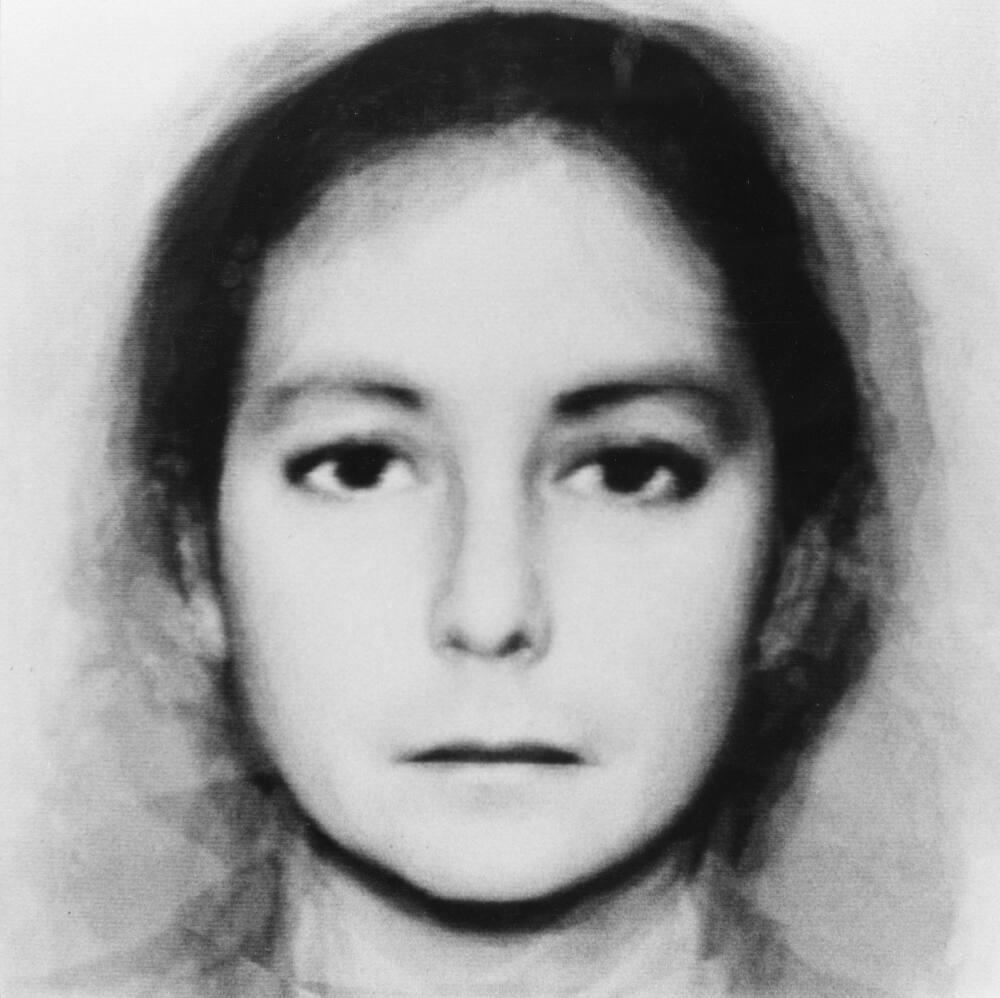

Currently, the morphing technology is in use by the FBI for locating kidnap victims and missing persons, but Burson first began unlocking its potential in her work by using it to address issues of race and gender. She created various series of composites that would become widely reproduced and emulated. Her earliest include Aged Barbie, and Beauty Composites, in which she creates a single digital image consisting of each era’s most revered Hollywood starlets, challenging imposed feminine ideals. She gave fear and power an identity with Warhead I, creating a face that consisted of 55% Reagan, 45% Brezhnev, and 1% Thatcher, Mitterand and Deng. In He/She, Burson created a series of androgynous individual faces, defying gender roles and their dictation of expected physical appearance. She gave humanity a face in her digital composites of Mankind, once in 1986, and again by repeating the experiment in 2003. In 1990, Nancy Burson proposed a new definition of beauty, going against the widely criticized mass media and its set definition of perfection with unapologetic captures of various physical conditions and anomalies in Craniofacial (Seeing).

By the 1980s, Burson was putting her morphing program to the test in the form of four interactive machines, including that which she had conceived twenty years earlier, the Age Machine. Two others included the Anomaly Machine, which allows users to see themselves with physical deformities, and the Couples Machine, which allows two participants to predict what their children could possibly look like. Most daring however, is Burson’s use of the digital technology to explore what would happen when genetic make up mixed across race and gender in the Human Race Machine (Seeing).

The Human Race Machine is an experiential tool that allows users to see themselves as a member of a different race, including Asian, Black, Middle Eastern, White, Hispanic and Indian. It garnered widespread recognition both for its universal message of acceptance, including the assertion that we are all one race and the claim that our genetic make up is 99.97% identical, and for its numerous potential applications in film, photography, computing, law enforcement, medicine and education. The machine is currently touring U.S. universities and colleges, providing students with the opportunity to experience cross-race similarities, shattering the stereotypes projected onto them, and in her own words “imaging the paradigm shift from ‘I-ness’ to ‘we-ness.’ ” (Boxer). Since the development of the Human Race Machine, however, digital technology has evolved, and with it, the machine’s applications and more opportunities for the artist to reach a wider audience with her message. In keeping with new media, the Human Race Machine now appears as a smartphone application, Racializer, enabling users around the world, and not only those in the U.S. with the privilege of accessing the machine, to experience Burson’s morphing technology and social message.

Burson’s involvement in various social causes continued. In the 1990’s, Burson collaborated with the National Cancer Institute to create educational posters for combating AIDS related illnesses using digital imaging technology. The project was titled Visualize This. Inspired by campaigns such as these and her earlier work with the Craniofacial composites, Burson created a new series of digital images and videos documenting the ill, their healers, the auras they emitted and magnified images of blood cells and disease, titled Healing and Pictures of health, promoting the power of positive thought in healing (Nancy).

In 2002, Nancy Burson worked with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC), in collaboration with Creative Time, to create a project titled Focus on Peace, “a citywide declaration that serves as a visualization/contemplation tool to shift our consciousness forward. It is a positive action message of healing and hope.” The aim was to distribute the message through 30,000 postcards and 7,000 posters for the first anniversary of September 11th, communicating through face-to-face interaction, and electronically through e-blasts (Nancy).

Burson’s social commentary continues to resonate through her art and writing. Most recently, she’s collaborated with Deutsche Bank, LMCC, and the city of New York to create several other public art projects, including There’s No Gene For Race, featuring five images of the same woman as a member of New York City’s various racial groups (Nancy). Though much of her work is based in New York City, her digital work and photography has been exhibited widely, including in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Venice Biennale, the International Center of Photography, and the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, with pieces permanently housed in the International Museum of Photography, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (MoCP).

Aside from her artwork and photography, Burson taught at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and as a visiting professor at Harvard University in the 1990s, and continues to lecture and present publicly. She also has several published books, four containing collections of her photographic work (Nancy). She lives and works in New York City’s SoHo district.

Nancy Burson’s contributions are far reaching, both working with and influencing traditional photography and the latest digital technology. As a pioneer in new media, she has pushed to see how far the technology will reach, and questioned how far society has yet to go. Burson initially set out as a photographer to challenge whether the perceived truly was reality, if seeing is believing. She succeeded, proving that beyond the physical world and our perceptions of it, there is an entirely different reality; a world of universal beauty and shared equality, where as a new media artist, she played the important part of bridging the gap between technology, art, and humanity.