As the United States became embroiled in the war in Europe against the Axis, one of its earliest fronts was in the air. With waves of American heavy bombers making the perilous trek across the skies of continental Europe to strike targets in the heart of Axis territories, they faced a deadly and unrelenting opponent.

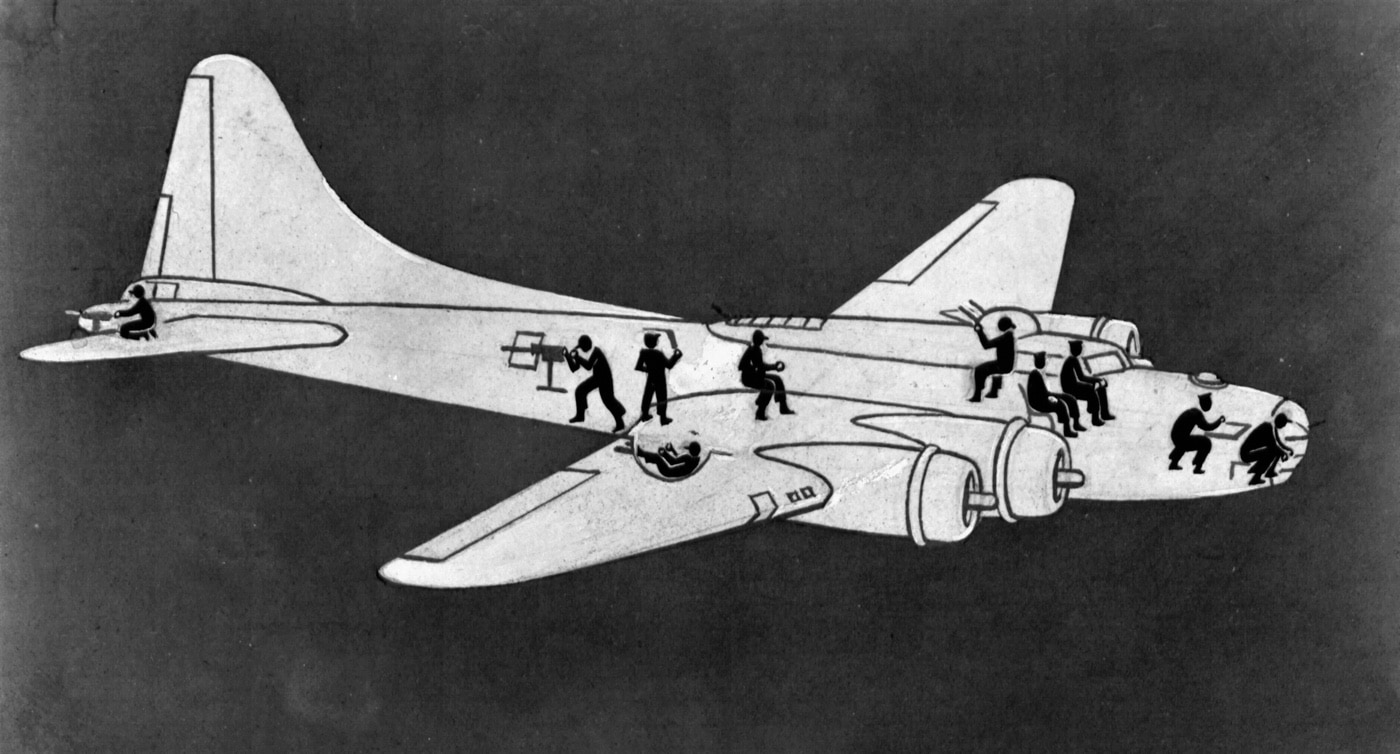

In the recent Apple+ TV series “Masters of the Air”, viewers got a look at the harrowing job of the B-17 Flying Fortress’ gunners. The Armory Life editors and I thought it would be a good idea to take a snapshot of the Boeing B-17 gunners’ battle against Luftwaffe interceptors during the 8th Air Force’s strategic bombing campaign over Germany.

The first B-17 raid against German targets came on August 17, 1942, when a dozen Flying Fortresses hit the railroad yards at Rouen, France. America’s concept of strategic bombing, using daylight raids to hit precise targets in Germany and Occupied Europe, was quickly put to the test.

Although the first B-17 raid to nearby France was closely guarded by four squadrons of RAF Spitfires, subsequent missions deeper into German-held territory could not be escorted at that time. By the summer of 1943, the number of B-17 groups based in England had increased dramatically, and the U.S. Army Air Force’s (USAAF) raids increasingly targeted industrial centers far into the Reich.

German flak forces concentrated hundreds of guns near important cities, and the Luftwaffe fighter force gathered a significant number of interceptors to cover Western Europe. The stage was set for a massive gunfight in the sky — not a “dogfight” as we think of in fighter-versus-fighter combat, but rather an aerial slugfest where there was no sneaking up on or out-turning anyone.

The B-17’s name “Flying Fortress” was based in reality. The earliest B-17 variants in combat over Europe (the B-17E), were armed with ten Browning A/N M2 .50 caliber machine guns, and this was steadily increased to thirteen .50 cal guns in the final B-17G model.

Even with its initial heavy armament, Luftwaffe fighters quickly sought to isolate bombers and take them down when they could not be supported by their squadron mates. As early as 1943, a USAAF report noted that more than 50% of all the heavy bombers destroyed were shot down outside the main formation.

Consequently, the “combat box” formation was adopted — and though it was more rigid and gave the flak gunners greater predictability of the bombers’ flight plan, the tight grouping of .50-cal. defensive guns made a B-17 group a particularly daunting target for interceptors.

Many of the B-17E and early F models lacked significant forward-firing guns, and it became clear to the Luftwaffe pilots that a head-on attack would receive the least amount of defensive fire. German interceptors began to use this tactic more and more throughout 1943, sometimes with great success.

However, it took steel nerves and steady aim for a Focke-Wulf or Messerschmitt pilot to get critical hits with a closing speed of 600 mph and just a second or two of firing time. If the fighters’ 20mm cannon struck home, the explosive shells usually smashed into engines or penetrated the nose and cockpit. Even though the B-17 was a flying fort, she was guided by men of flesh and bone.

Field modifications for the B-17F mounted a pair of .50-cal. guns directly in the nose, but this fitting was heavy and not easy to aim, and the bulk of the guns and ammunition were not necessarily welcome in the cramped nose of the Fortress.

The B-17s were fighting a losing battle in the late summer of 1943, with flak and Luftwaffe interceptors taking a terrible toll of bombers striking deep within the Reich. Lt. Col. Beirne Lay, flying a B-17F (Piccadilly Lilly) with the 351st Bomb Squadron/100th Bomb Group describes the fighter attacks he experienced on a mission to Regensberg, August 17, 1943:

Fighter tactics were running true to form. Frontal attacks hit the low squadron and lead squadron, while rear attackers went for the high. The manner of their attacks showed that some pilots were old-timers, some amateurs, and that all knew where we were going and were inspired with a fanatical determination to stop us before we got there.

The old-timers came in on frontal attacks with a noticeably slower rate of closure, apparently throttled back, obtaining greater accuracy than those that bolted through us wide open. They did some nice shooting at ranges of 500 or more yards, and in many cases seemed able to time their thrusts to catch the top and ball turret gunners engaged with rear and side attacks.

Less experienced pilots were pressing attacks home to 250 yards and less to get hits, offering pointblank targets on the breakaway, firing long bursts of 20 seconds, and in some cases actually pulling up instead of going down and out. Several Fw pilots pulled off some first-rate deflection shooting on side attacks against the high group, then raked the low group on the breakaway out of a sideslip, keeping the nose cocked up in the turn to prolong the period the formation was in their sights.

The Germans shot down 24 B-17s on that mission to Regensburg, along with 36 B-17s sent to Schweinfurt that same day — totaling 60 bombers lost in one day. The Fortresses kept up their attacks, and the Germans continued to improve their interception techniques. In October 1943, the 8th Air Force lost nearly 180 bombers.

With the losses of aircraft and trained aircrews becoming unsustainable, the days of unescorted daylight raids were coming to an end. In February 1944, the arrival of long-range escorts, P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, equipped with drop-tanks for extended range, signaled the beginning of a new round of gun fights in the sky.

Escorted or not, the challenges of the B-17 gunners remained the same. German fighters hurtled in at high speed, cannon muzzles flashing.

On November 2, 1944 an escorted, thousand-plus bomber raid against the Leuna-Merseburg refinery was opposed by nearly 300 Luftwaffe interceptors. Staff Sergeant Bernard Sitek, a B-17 ball turret gunner from the 457th Bomb Group commented: “I got my gun sights on him from about 600 yards as he made his attack from seven o’clock. I could almost see the bullets hit home. As he got closer, I could feel his 20mm bursts around me. At about 200 yards distance he seemed to stop dead. He rolled over and the pilot came out. In a split second the plane burst into flames and broke into several pieces.”

The job of the air gunners was difficult from the start, and it never got any easier. Stateside training was long and intensive, but the combat squadrons still found their new gunners lacking in some critical skills.

Training in the USA contained a large amount of classroom time spent on the concepts of aerial gunnery. One of the biggest complaints about new gunners from 8th AF squadron commanders was that many of the men did not know how to maintain the Browning AN/M2 machine gun. Beyond that, some new men were unfamiliar with the B-17 turrets and how to troubleshoot them in flight.

Various bomb groups created their own advanced training centers, some of them leveraging sophisticated audio/visual training aids for the time. Just as American airmen had learned in World War I, gunners benefited from continuous practice. As the missions continued, the gunners came to know every detail of the Browning guns and their various mounts.

In late 1943, the B-17G entered service — the ultimate (and most produced) variant of the Flying Fortress. The B-17G featured additional armament in the nose in the form of a twin-gun “chin turret”, operated by the bombardier. Single gun cheek blisters became standard on both sides of the nose. Coupled with the top turret, the additional nose guns gave the Flying Fortress a stronger defense against frontal attacks by German fighters.

But in the move and counter-move nature of the aerial gunfights over the Reich, Luftwaffe interceptors responded by increasing the caliber and amount of the cannons they carried. German pilots sought to find enough killing power to knock down a B-17 while they stayed outside the 600-yard effective range of the Fortresses’ .50-cal. machine guns. The Fortresses’ defensive gunfire was not necessarily that accurate, but in many cases, it was intensive and intimidating. It took a particularly brave Luftwaffe pilot to close on a formation of B-17s, with hundreds of tracers flying into his face. Many broke off their attacks too early to achieve the full effect needed to bring down a Flying Fortress.

While the B-17 air gunners fought hundreds of individual battles, blasting away at any German interceptor they could get their sights on, they rarely received the individual recognition for multiple “kills” like that given to fighter pilots. Researchers Charles Watry and Duane Hall described the extremely complicated scoring system applied to the aerial gunners:

In getting their licks in, gunners of the Eighth Air Force could claim victories under the guidelines of some rather rigid rules. To qualify for a claim of destroyed the plane had to be completely engulfed in flame and be confirmed by a witness. If flames were sighted coming out of the engine or a wing, that was not sufficient for a destroyed claim.

A destroyed claim could also be granted if the airplane was seen to explode and disintegrate completely in midair, or if a wing or tail assembly were seen shot completely away. If the fighter was a single-cockpit machine, a destroyed claim could be awarded if the pilot were seen to bail out. Of course, if the aircraft were witnessed to crash into the ground after being hit, a destroyed claim could be awarded.

A claim of probably destroyed, or probable, could be awarded if the plane was so badly shot up or completely on fire that it seemed unlikely it would have survived. A claim of damaged could be earned if parts of the aircraft were seen to fly off, but not if bullets struck the fighter without visible parts being shot away.

Several gunners made “ace” status, but their achievements were rarely celebrated outside their own bomb group. They truly were the unknown aces of WWII.

The mighty Browning AN/M2 .50 caliber machine gun was more than capable of defending the Flying Fortress, with an effective air-to-air range of approximately 700 yards. Muzzle velocity was 2,910 fps, and the cyclic rate was up to 850 rounds per minute.

The gunners maintained their own weapons and learned to fire in controlled bursts to conserve ammunition throughout the long flights. The usual ammunition load for the B-17s MGs included AP (armor-piercing), armor-piercing incendiary (API), and armor-piercing incendiary tracer (APIT) rounds.

The B-17 turrets provided stable mountings despite the heavy recoil of the .50-cal. guns, but for the waist gunners, using their “flexible” guns on pedestal mounts, it was quite a different story. To give the gunners greater control and stability, the waist guns were fitted with the Bell Machine Gun Adapter (Model GM 43).

Without the damping effects of this adapter, the recoil forces of the .50-cal. MG made accurate shooting nearly impossible. Sights for the waist guns were normally a ring and post, and the gunners worked back-to-back, in slightly staggered positions. The more they fired, the more the spent .50 caliber casings mounded up at their feet.

Sights for the top and belly turrets were the more sophisticated Sperry K-3/K-4 computing gun sights: the sight’s computing unit coupled range with on-board ballistic data to calculate the proper deflection and moved the turret automatically to the aiming point.

B-17 tail guns began with a simple ring and post sight but graduated to a N-8a reflector sight when the “Cheyenne” tail turret was introduced on later B-17Gs. The tail position was a tight fit, accessible by a narrow tunnel. The gunner sat on a bicycle-style seat and worked in an uncomfortable kneeling position. The twin tail guns were provided with 565 rounds each.

Unique challenges in operating the Browning MGs at high altitude were encountered. To counteract the impact of the extreme cold (as low as 40-below zero) the guns were provided with heaters, normally the 24-volt “DC AN-J4”.

Through all the flak and enemy fighters, despite frost-bitten hands and with never-enough ammunition, the B-17 gunners and their Browning .50-cal. guns were there at the beginning of the 8th AF’s bombing campaign, and they stayed in the fight until the 3rd Reich crumbled beneath them.