Front page story, New York Times, April 28th, 1947.

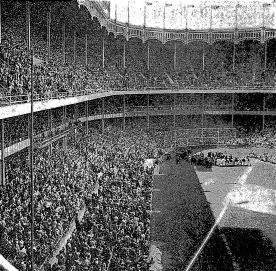

Front page story, New York Times, April 28th, 1947.It was April 1947. America was about to begin its post-World War II economic boom. A few months earlier, Edwin Land had demonstrated his “instant camera”, the Polaroid Land Camera. Radio was still the principal communications medium, with more than 40 million strong. Television, at a scant 44,000 sets nationwide, was just starting. As a new baseball season began, a special day was set aside to honor former New York Yankee baseball star, Babe Ruth. More than 58,000 fans packed Yankee stadium on April 27th to honor Ruth, along with American and National League baseball officials, Catholic Archbishop Francis Cardinal Spellman, and other VIPs who were also in attendance. The ceremony and speeches were piped into all Major League and many Minor League baseball parks that day. Babe Ruth was then 12 years retired from active play; a new generation of players had taken the field such as Joe DiMaggio. Still, Ruth had set baseball’s most revered record 20 years earlier — hitting an unheard of 60 home runs in one season. In the intervening years a few players had hit as many as 58 home runs in one season, but no one had broken Ruth’s record. And his career total of 714 home runs appeared to be invincible.

Yankee Stadium, Babe Ruth Day, April 27th, 1947.

Yankee Stadium, Babe Ruth Day, April 27th, 1947.In June 1948, at a second celebration commemorating the 25th anniversary of Yankee Stadium — known as “the House that Ruth Built” — the slugger was again honored (see photo below). His Yankee uniform playing numeral, No. 3 was formally retired that day.

“Saved” Baseball

Babe Ruth, throughout his career, had made important contributions to the Yankees, New York city, and all of professional baseball. In the 1920s, his hitting prowess not only made millions of dollars for the New York Yankee franchise, but also “saved” baseball from national disgrace. The 1919 Chicago Black Sox scandal — when players took bribes to throw the World Series — had badly tainted all of baseball. But Babe Ruth, with his home runs and out-sized personality, came along at just the right time. He wasn’t the only factor in the revival, certainly, but his power and celebrity helped energize the game, reclaim its respectability, and renew and expand the fan base. In so doing, he helped to elevate baseball’s place in American culture and to make it a much bigger business.

In the go-go 1920s, before the Stock Market crash, Ruth had been something of a symbol of American optimism; the sports hero with the big smile and big appetite who seemed to make anything possible. By 1947 and 1948, of course, a lot had changed. WWII and the Great Depression were then in the past. But the fans who came out to give their final cheers for Ruth at Yankee Stadium in 1947 and 1948, were also cheering for the 1920s American optimism and derring-do that Ruth stood for, as well as his awesome accomplishments.

June 13, 1948: Babe Ruth in his last appearance at Yankee Stadium, captured in Nat Fein’s Pulitzer Prize winning photo.

June 13, 1948: Babe Ruth in his last appearance at Yankee Stadium, captured in Nat Fein’s Pulitzer Prize winning photo.George Herman Ruth, born in 1895, had come to baseball via the school of hard knocks. A Baltimore saloonkeeper’s son, Ruth had been something of a problem child, and at the age of 7, his parents placed him in St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys for his “incorrigible” behavior. The school was run by Catholic Xaverian brothers, and Ruth spent almost his entire youth there. The school became the place where Ruth — with the help and encouragement of Brother Matthias Boutlier — developed into a promising baseball player. By 1914, he was signed briefly to a minor league team before being sold with others to the Boston Red Sox.

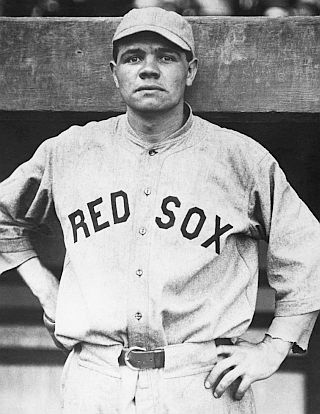

Babe Ruth with the Boston Red Sox, circa 1917-1918.

Babe Ruth with the Boston Red Sox, circa 1917-1918.Boston Phenom

In Boston, the left-handed Ruth became a formidable pitcher as well as a promising hitter. His pitching, in fact, helped Boston win two World Series in 1916 and 1918. He was later converted to an outfielder in Boston so he could play more often, making use of his hitting power. He did not disappoint.

In 1919, his last year with Boston before coming to the Yankees, he hit 29 home runs, breaking the existing record. Before that, no one had ever hit more than 25 home runs in one season. News of Ruth’s batting feats in Boston spread. Wherever he played, large crowds filled the stands.

In the winter of 1919, however, Boston’s owner Harry Frazee, in need of money to finance his business interests on Broadway, sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees for about $100,000 and a $300,000 loan. With the Yankees, Ruth would soon become the dominant player in all of professional baseball.

“Small Ball” No More

In the decade preceding the 1920s, baseball was not a game of home runs and high drama. Rather, it was a game of singles, bunts and stolen bases; what might be called “small ball” in today’s lingo – a game of hustle with batters hitting for direction, not distance. Few players ever hit more than a dozen or so home runs per season prior to 1919. Pitchers dominated, then using the spitball, often aided by tobacco-juice. In those days, only one ball was used for the entire game – a time known as “the dead ball” era. By 1920, some rule changes had come to the game. The spitball was outlawed along with unorthodox pitching deliveries and the ball began to be replaced regularly during a game. One player, in fact, had been killed after being hit in the head with a dirty, darkened ball.

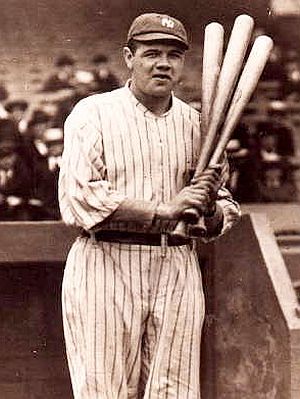

Ruth in his early days with the NY Yankees.

Ruth in his early days with the NY Yankees.When Ruth began play with the Yankees in 1920, the team then shared the Polo Grounds stadium with the neighboring New York Giants of the National League. On May 1st that year, Ruth hit his first Yankee home run, a ball that left the Polo Grounds. By year’s end, Ruth had hit a prodigious 54 home runs, nearly doubling the existing record. No other player that year had hit more than 19 home runs. Ruth also batted for a .376 average with a slugging average of .847 – the latter a record that would stand for 80 years. The Yankees that year also shattered the league’s annual attendance mark, drawing 1.3 million fans, breaking the old mark of 900,000 set in 1908. In the following year, 1921, Ruth hit 59 home runs. Only the Philadelphia Phillies – as an entire team – hit more at 64. The “small ball” era was long gone.

A Good Investment

In the Yankee front office, meanwhile, Ruth was proving to be a very good investment. Home receipts more than doubled in each of the years 1920-1922, and the Yankees also appeared in the 1921 and 1922 World Series, producing an additional $150,000 in revenues. The Yankee share of road receipts more than doubled in each of those years as well. In 1923, Ruth continued to excel. He set a career-high batting average of .393 that year and led the major leagues with 41 home runs. The 1923 season also saw the opening of Yankee Stadium, with Ruth hitting the stadium’s first home run in the opening game, prompting sportswriter Fred Lieb to nickname the place, “The House That Ruth Built.” In 1923, for the third straight time, the Yankees faced the Giants in the World Series. Ruth hit .368 for the series, scored eight runs, and hit three home runs. The Yankees won the series 4 games to 2.

1924: Babe Ruth with George Sisler of the St. Louis Browns, one of the game’s all-time greats, who in 1922 had hit safely in 41 consecutive games and complied a .420 batting average.

1924: Babe Ruth with George Sisler of the St. Louis Browns, one of the game’s all-time greats, who in 1922 had hit safely in 41 consecutive games and complied a .420 batting average.In New York, and on the road, fans were turning out see Ruth in droves. One reporter wrote, “This new fan didn’t know where first base was, but he had heard of Babe Ruth and wanted to see him hit a home run. . .” Ruth was also generating a lot of attention with his outsized personality and off-the-field carousing. He had larger-than-life appetites and eventually became one of the enduring personalities of the roaring ’20s. The large New York Italian immigrant community gave him the nickname “bambino.” To many people, Ruth was more than a baseball player, he was a national icon. Yet some say Ruth never quite grew up as person; at times he could be down right crude. He drank, gambled, scoffed at training rules, and would argue with umpires and abusive fans. Still, New York City proved the perfect place for Ruth — the big star on a big stage, with big crowds and big media coverage. He lived large and earned over $2 million, most of which he spent. Yet Ruth could be very generous and caring, and would go out of his way for some people, and especially for sick children and orphans.

By December 1925, however, Ruth’s high living was beginning to show; he was overweight at 254 pounds, had a high pulse, fat stomach, and was generally out of shape. With the help of fitness coach Artie McGovern, Ruth changed his diet and got back into shape. He also kept McGovern as his trainer. In 1926, Ruth compiled an impressive .372 batting average with 47 home runs and 146 RBIs, leading the Yankees back to the World Series. Though they lost the Series to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games, Ruth hit three home runs in game 4.

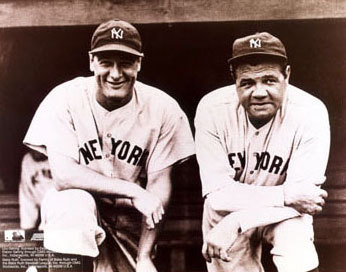

In 1927, Lou Gehrig & Babe Ruth combined for 107 home runs and 339 RBIs. Click for story on their 1927 home run race & the media that year.

In 1927, Lou Gehrig & Babe Ruth combined for 107 home runs and 339 RBIs. Click for story on their 1927 home run race & the media that year.Yankee Power

By 1927, the New York Yankees had built one of the greatest teams of all time, compiling a 110-44 record, sweeping the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. That was the year Ruth hit his record-setting 60 home runs, a time when teammate Lou Gehrig was also becoming a powerhouse. In addition to Ruth’s record 60 home runs that year, he also batted .356, drove in 164 runs, and complied a slugging avg of .772 – all phenomenally impressive baseball feats.

In the following year Ruth had 54 home runs. In fact, from 1928 through 1934, Ruth continued to produce at that level, with very good numbers: batting averages of .300 or more every year except 1934, and hitting 40 or more home runs in each of those years except 1933 and 1934 when he hit respectively, 34 and 22 home runs.

In 1930, during spring training in Florida, when Ruth was negotiating for a higher salary — he wanted $100,000 a year, but signed for $80,000 — a reporter pointed out that he was now making a higher salary than President Herbert Hoover. Ruth replied, “I had a better year.”

Celebrity Ruth

Although not a person active in politics, Babe Ruth supported NY Governor Al Smith (D) for President in 1928, shown here with Smith in an undated photo.

Although not a person active in politics, Babe Ruth supported NY Governor Al Smith (D) for President in 1928, shown here with Smith in an undated photo.During the prime of his career, Babe Ruth was one of the most sought-after celebrities of his day. Sportswriters and newsmen, of course, wanted Babe Ruth in their stories. But advertisers and politicians also wanted Ruth to back their products or endorse their political campaigns. He appeared in numerous print ads for products ranging from breakfast cereals and shaving cream to sporting goods and tobacco products.

Although he rarely if ever voted, he supported the 1928 presidential candidacy of New York Governor Al Smith (D), speaking on radio a few times on Smith’s behalf, and also attending at least one political convention where he introduced fellow Yankee ballplayers Lou Gehrig and Tony Lazzeri, who supported Smith as well. Ruth, in fact, refused to appear with then sitting U.S. President Herbert Hoover at a baseball game in Washington, DC in September, saying he was “an Al Smith man,” although he later apologized for the slight. In later years, Ruth did appear in a photograph with then former President Herbert Hoover, taken on November 11th, 1933 at a Stanford-USC football game. Ruth also had roles in a number of short films during the late 1920s and early 1930s, and would often appear in promotional photos with various movie and entertainment stars.

By 1935, as Ruth’s career was coming to an end, the New York Yankees traded him to the National League’s Boston Braves. But Babe Ruth still had one last hurrah left.

The Last Hurrah

On May 25,1935, against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field, the 41-year old Ruth had four hits in the game, a rare feat on its own. But three of Ruth’s hits that day were home runs: one in the first inning that went over the right-center field wall; a second in the third inning to deep right field; and a third, monster drive in the ninth inning that the Associated Press then described as “a prodigious clout that carried clear over the right field grandstand, bounded into the street, and rolled into Schenley Park.” It was the first baseball ever hit out of Forbes Field. That homer brought a standing ovation for Ruth from the sparse crowd of 10,000 that day as he rounded the bases for his 714th career home run. It would be Ruth’s final home run.

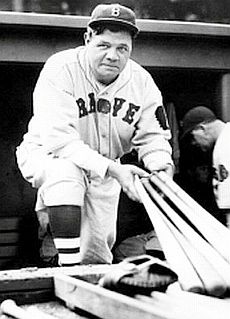

Ruth at career end with the Boston Braves in 1935, the year he hit 3 home runs in one game at Pittsburgh at age 41.

Ruth at career end with the Boston Braves in 1935, the year he hit 3 home runs in one game at Pittsburgh at age 41.In early June 1935, Babe Ruth voluntarily retired from baseball and was released by the Braves. In the years that followed, Ruth did some coaching but never became a manager, which he had always wanted to do. In 1936, when the Baseball Hall of Fame was instituted, Babe Ruth was among the first five players elected, along with Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson and Honus Wagner.

In retirement, Ruth made special appearances, played in occasional exhibition games in the U.S. and abroad, and endorsed a variety of products. He also gave talks on the radio, at orphanages and hospitals, and served as a spokesperson for U.S. War Bonds during World War II.

By 1946, however, he had been diagnosed with throat cancer and although treated, doctors could do little to help him. His treatment had ended just a few months before his appearance at Yankee Stadium for the April 1947 Babe Ruth Day celebration. It was apparent to most who saw him that day that Ruth was a sick man. Having lost weight, he was not the robust player most remembered. Still, he was greeted with a great roar of the crowd after the initial convocation by Cardinal Spellman and the introductions by Major League baseball officials.

“Just before he spoke,” explained a New York Times reporter at the ceremony, “Ruth started to cough and it appeared that he might break down because of the thunderous cheers that came his way. But once he started to talk, he was all right, still the champion. It was the many men who surrounded him on the field, players, newspaper and radio persons, who choked up.” Ruth’s Hall of Fame plaque says he was the “greatest drawing card in history of baseball.”Ruth began his speech from the microphone on the field at home plate in a very raspy, painful sounding voice. “Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen. You know how bad my voice sounds,” he said. “Well, it feels just as bad.” He proceeded to talk briefly about the game of baseball and how important it was to keep the youth of the country involved in the game. He then thanked the fans and the earlier speakers for their words of praise, and with a wave to the fans, walked from the field down into the Yankee dugout. Beneath the stands he had a few trying minutes, coughing again, before he was able to join his wife, daughter, and other friends in a boxed seat to watch the game.

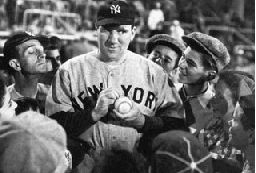

Actor William Bendix as Ruth in scene from 1948 film, ‘The Babe Ruth Story.’ Click for film.

Actor William Bendix as Ruth in scene from 1948 film, ‘The Babe Ruth Story.’ Click for film.Ruth made his final Yankee Stadium appearance less than a year later on June 13, 1948, at the 25th anniversary of Yankee Stadium. Dressed in his old Yankee uniform that day (see earlier photo, above), Ruth again was honored and his Yankee No. 3 jersey retired from service.

The next time he appeared in public, his last, was on July 26th that year for the New York premier of a Hollywood movie, The Babe Ruth Story, with actor William Bendix playing Ruth. Shortly thereafter he was back in the hospital.

On August 16th, 1948, Babe Ruth died of throat cancer. He was 53. For two days Ruth’s body lay in state at the entrance to Yankee Stadium where tens of thousands came to pay their last respects. A Requiem Mass was held for Ruth at St. Patrick’s Cathedral with Francis Cardinal Spellman presiding. About 6,000 people attended the service, with New York Governor Thomas Dewey, New York Mayor William O’Dwyer, and Boston Mayor James Michael Curley serving as pallbearers.

Impressive Legacy

Babe Ruth left behind a professional baseball legacy that few other players would ever equal. His Hall of Fame plaque says, among other things, that he was the “greatest drawing card in history of baseball.” At the time of his death in 1948, Ruth is said to have set or tied 76 baseball records, a number of which have since been overtaken. Yet some of Ruth’s achievements stood for decades.

Ruth had set the single-season home run mark at 60 in 1927, a time when most entire teams wouldn’t reach that mark. Ruth’s record stood for 34 years until Yankee Roger Maris broke it in September 1961 (Maris and Mickey Mantle had engaged in a home run race that summer to topple the record). Ruth was also the first player to hit respectively more that 30, 40, and 50 home runs in one season. His career home run record of 714 wasn’t broken until Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves surpassed it in 1974. And Ruth was surprisingly durable too, considering his living-large habits. He played more than 20 years in the big leagues.

Babe Ruth in action, 1931, at Oriole Park, Baltimore, Maryland. Photo from Robert F. Kniesche / Kniesche Collection / Maryland Historical Society.

Babe Ruth in action, 1931, at Oriole Park, Baltimore, Maryland. Photo from Robert F. Kniesche / Kniesche Collection / Maryland Historical Society.Along with his home runs, Babe Ruth put in more seasons, had more hits, more extra-base hits, more runs scored, and more runs batted-in than many of the other Yankee greats, including Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, and Mickey Mantle. Ruth led the Yankees to seven American League pennants and four World Series titles, hitting a total of 15 home runs in World Series play. He is the only player ever to hit three home runs in a World Series game on two separate occasions — game 4 of the 1926 World Series and game 4 of the 1928 World Series. Unlike many home run hitters, Ruth had a very good batting average. Wrote the Sporting News in 1999, naming him to its 100 Greatest Players list: “Lost in the fog of Ruth’s 12 American League home run titles, four 50-homer seasons, and six RBI titles was a career .342 average that ties for eighth all-time in baseball’s modern era.”Ruth’s “Louisville slugger” baseball bat — used to hit the first home run at Yankee Stadium in 1923 — was sold at Sotheby’s in 2004 for $1.26 million. Ruth’s career .690 slugging percentage (calculated by dividing total bases by at-bats) is the highest total in the history of Major League Baseball. As a pitcher in his early years with the Red Sox, Ruth won 89 games in six years and set a World Series record for consecutive scoreless innings pitched. From 1915-17, Ruth won 65 games, the most by any left-handed pitcher in the majors during that time.

Ruth’s name and legend have been enshrined in baseball history and active baseball play. In 1953, an organized baseball league for boys aged 13-to-15 was named Babe Ruth League Baseball. In 1969, Ruth was named baseball’s Greatest Player Ever in a ballot commemorating the 100th anniversary of the game. And in 1999, voting by baseball fans put Ruth on the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. Ruth’s popularity, and indeed his continuing commercial value, is seen in the recent prices paid at auction for Ruth memorabilia. Ruth’s 1923 solid ash, Louisville Slugger baseball bat used to hit the first home run at Yankee Stadium in April 1923 was sold at a Sotheby’s in December 2004 for $1.26 million. The 1919 contract that sent Ruth from the Boston Red Sox to the New York Yankees was sold by Sotheby’s on June 10, 2005 for $996,000. Ruth’s name and image — used variously in advertising and other commercial uses — continues to be under management by a public relations firm. His life has also been the subject of numerous books and web sites, including the 2006 book, The Big Bam, the cover of which is shown below in “Sources”.

Ruth plugged Wheaties cereal in radio spots & print ads in the 1930s. Sixty years later, in 1992, he appeared on a ‘sports heritage’ Wheaties box.

Ruth plugged Wheaties cereal in radio spots & print ads in the 1930s. Sixty years later, in 1992, he appeared on a ‘sports heritage’ Wheaties box.Others Cash In

Ruth’s image has also appeared in a variety of corporate advertising and marketing campaigns — Chevrolet, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Hallmark, Zenith, Sears, and others. In the mid-1990s, royalties and licensing fees from Ruth advertising and other ventures were expected to run “well into seven figures,” according to CMG’s Mark Roesler.

Jerry Amernic’s 2018 book, “Babe Ruth, A Superstar’s Legacy”, Wordcraft Com., 240pp. Click for copy.

Jerry Amernic’s 2018 book, “Babe Ruth, A Superstar’s Legacy”, Wordcraft Com., 240pp. Click for copy.In the 1980s, Roesler and CMG had located Ruth’s surviving relatives and struck a deal with them, with CMG keeping 60 percent of sales and the Ruth family and Babe Ruth League Baseball getting the remainder. By 1985, modest checks began arriving for the family in the $5,000 range, and by the early 1990s the family was receiving amounts of up to six figures annually. CMG at that time was still taking its 60 percent cut. Since the mid-2000s, however, the Luminary Group of Shelbyville, Indiana, appears to have acquired the Babe Ruth account.