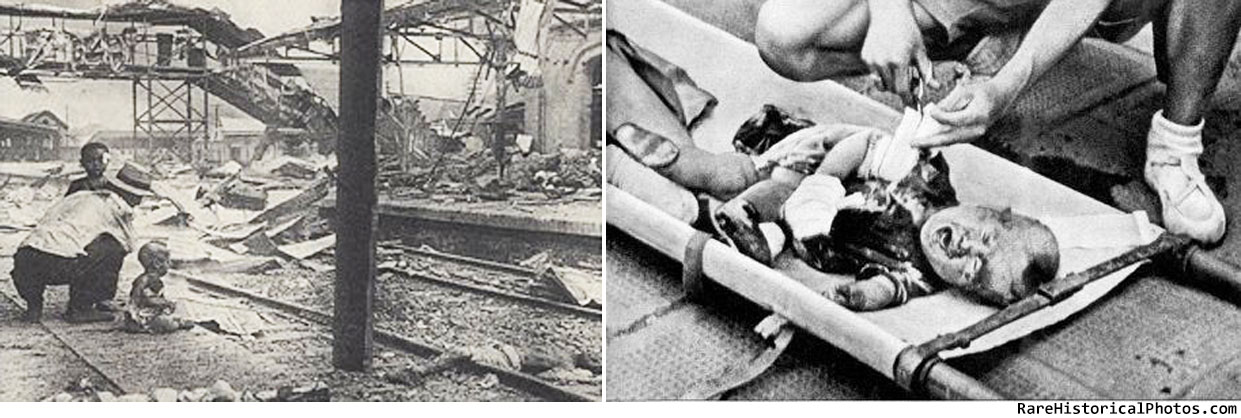

“Bloody Saturday” – An iconic photo of a crying baby amid the bombed-out ruins of Shanghai’s South Railway Station after a Japanese air strike against civilians. August 28, 1937.

“Bloody Saturday” – Depicting a Chinese baby crying within the bombed-out ruins of Shanghai South Railway Station, the photograph became known as a cultural icon demonstrating Japanese wartime atrocities in China.

Taken a few minutes after a Japanese air attack on civilians during the Battle of Shanghai, Hearst Corporation photographer H. S. “Newsreel” Wong, did not discover the identity or even the sex of the injured child, whose mother lay dead nearby.

One of the most memorable war photographs ever published, and perhaps the most famous newsreel scene of the 1930s, the image stimulated an outpouring of western anger against Japanese violence in China. Journalist Harold Isaacs called the iconic image “one of the most successful propaganda pieces of all time”.

Wong shot footage of the bombed-out South Station with his Eyemo newsreel camera, and he took several still photographs with his Leica. The famous still image, taken from the Leica, is not often referred to by name—rather, its visual elements are described. It has also been called Motherless Chinese Baby, Chinese Baby, and The Baby in the Shanghai Railroad Station.

During the Battle of Shanghai, part of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japanese military forces advanced upon and attacked Shanghai, China’s most populous city. Wong descended from the rooftop to the street, where he got into his car and drove quickly toward the ruined railway station. When he arrived, he noted carnage and confusion:

“It was a horrible sight. People were still trying to get up. Dead and injured lay strewn across the tracks and platform. Limbs lay all over the place. Only my work helped me forget what I was seeing.

I stopped to reload my camera. I noticed that my shoes were soaked with blood. I walked across the railway tracks, and made many long scenes with the burning overhead bridge in the background.

Then I saw a man pick up a baby from the tracks and carry him to the platform. He went back to get another badly injured child. The mother lay dead on the tracks.

As I filmed this tragedy, I heard the sound of planes returning. Quickly, I shot my remaining few feet [of film] on the baby. I ran toward the child, intending to carry him to safety, but the father returned. The bombers passed overhead. No bombs were dropped.”

The baby on a stretcher, receiving first aid.

Wong never discovered the name of the burned and crying baby, whether it was a boy or a girl, or whether it survived. The next morning, he took the film from his Leica camera to the offices of China Press, where he showed enlargements to Malcolm Rosholt, saying, “Look at this one!”.

Wong later wrote that the next morning’s newspapers reported that some 1,800 people, mostly women, and children, had been waiting at the railway station, and that the IJN aviators had likely mistaken them for a troop movement. The Shanghai papers said that fewer than 300 people survived the attack. In October of that year, Life magazine reported about 200 dead.

Bloody Saturday photograph was published widely in September–October 1937 and in less than a month had been seen by more than 136 million viewers.

The photograph was denounced by Japanese nationalists who argued that it was staged. The Japanese government put a bounty of $50,000 on Wong’s head: an amount equivalent to $900,000 in 2021.

During the Second Sino-Japanese war Chinese sources list the total number of military and non-military casualties, both dead and wounded, at 35 million. Most Western historians believed that the total number of casualties was at least 20 million.