At the outset of World War II, the United States was largely unprepared for the conflict to come. Many of the planes in America’s inventory were obsolete, or close to it. One of those was the Douglas B-18 Bolo heavy bomber.

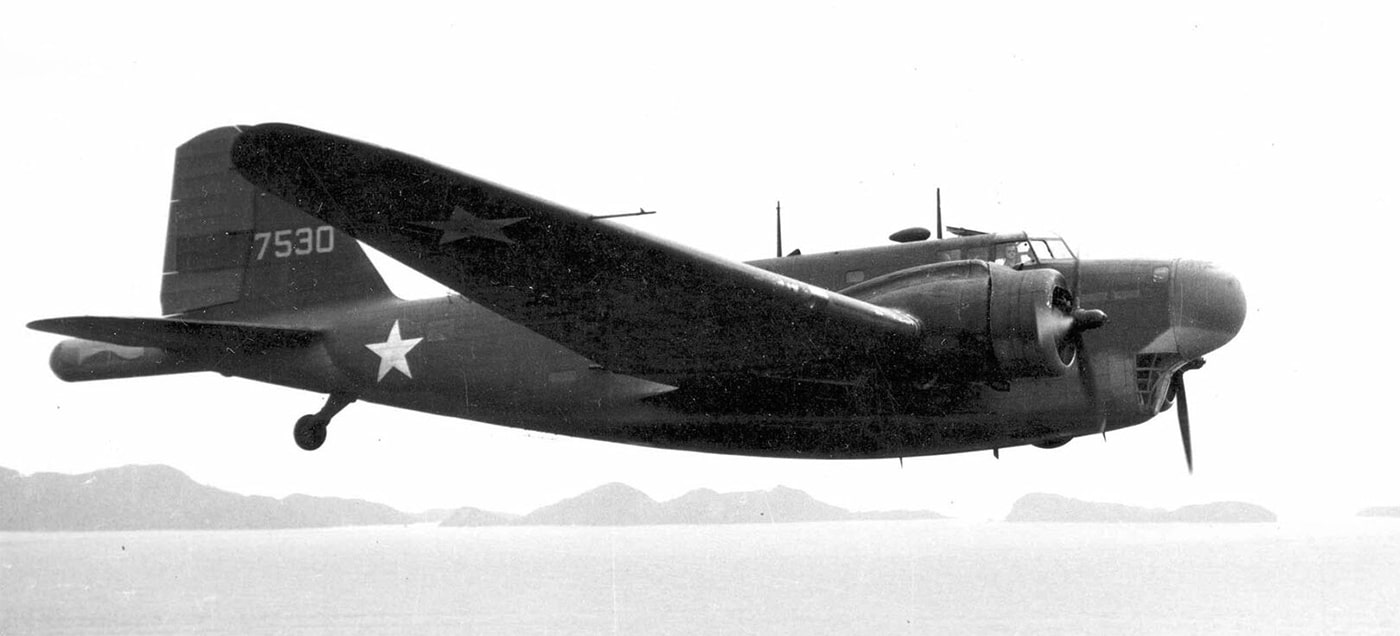

This Douglas B-18 Bolo bomber is in flight over Hamilton Field, California on February 7, 1938. Soon, these planes were tested in the fiery crucible of combat. Note it’s relatively flat nose. Image: NARA

The Bolo was vastly inferior to the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, yet it still somehow beat the Boeing B-17 prototype in the military trials. Consequently, Douglas got the early contract for heavy bomber production.

Many Bolos were destroyed in the initial Japanese attacks against the USA in late 1941 and early 1942. However, the planes still played a small, but important, role in World War II. After military service, a number of surviving B-18s saw service in fighting fires and one was even caught running guns to Fidel Castro in Cuba.

On May 3, 1940, nearly 30 B-18 bombers were closely packed together in this photo of Hickam Field in Hawaii. This parking method changed once the bullets began flying in December of 1941. Image: U.S. Navy

Even so, many people have never heard of the plane. Let’s take a look at this interesting bomber from the Douglas Aircraft Company.

Entering the mid-1930s, the United States had, arguably, one of the most advanced bombers to date: the Martin B-10. It was faster than any fighter of its era and introduced many new bomber design concepts that would be influential throughout the 20th century. However, it had a limited payload, and technology advancements quickly rendered it obsolete. The Douglas B-18 was intended to be a heavy bomber that would replace the B-10.

A flight of Douglas B-18 Bolo bombers fly in formation during exercises near Hawaii, taken in 1940-1941. Image: Harold Wahlberg

The United States Army Air Corps (later renamed to the United States Army Air Force) wanted a bomber to replace the B-10. They were looking for something with double the bomb capacity and range of the older plane. Douglas presented the DB-1, a company name for what would become the B-18.

It had stiff competition from the Boeing Model 299 and the Martin 146. The Model 299 would later be adopted as the magnificent B-17 while the Martin was a complete bust and was eventually scrapped. Interestingly, Martin was so disappointed with the performance of the Model 146 that it took a fresh look at bomber development and designed the very successful B-26 Marauder.

U.S. Army Air Corps servicemen working a Douglas B-18 Bolo aircraft sometime in the 1930s. Image: Sgt. Lee R. Embree/U.S. Air Force

The B-18 design was based on the Douglas DC-2. The DC-2 was a commercial passenger plane that really proved civilian passenger air travel could be reliable and comfortable. Initially, the DC-2 commercial planes were flown by Transcontinental & Western Air (TWA). Both Pan American Airways (Pan Am) and the KLM Royal Dutch Airlines would also purchase the DC-2 airliners. The DC-2 was later developed into the DC-3, which was possibly the most successful aircraft ever created.

This B-18A features the relocated bomardier position and the corresponding nose alteration. This specific plane was in Canadian service. Image: Dept. of National Defence

Douglas’s twin engine DB-1 beat the Boeing based on three main points:

- The USAAC requested a twin engine bomber, and the Model 299 had four.

- The DB-1 was substantially cheaper than the Model 299.

- The Model 299 prototype crashed during take off.

The U.S. Army Air Corps placed an order for 132 additional DB-1 bombers in January 1936 and designated it the B-18.

Armament on the B-18 was weak when compared to it’s eventual replacement, the B-17. However, it had a fair amount of defensive firepower for the time. Three .30-caliber (7.62mm) machine gun turrets were used on the plane: nose, dorsal and ventral positions. They were all manually operated by the crew of six men.

Douglas developed a DB-2 prototype that had a Tucker powered nose turret. These did not go into production and only one DB-2 was ever made. Image: U.S. Air Force

Douglas experimented with Tucker remote controlled gun turrets on the planes. One DB-2 was manufactured that used a Tucker powered nose gun turret. However, these were never adopted in production planes.

B-18A models received more powerful engines and relocated the bombardier position. Two orders of these were made — one for 177 bombers in 1937 and one for 40 airplanes in 1938. By 1939, however, it was obvious that the B-18 was vastly outmatched by other countries. Both the Japanese G3M Nell and Soviet Ilyushin DB-3 carried heavier bomb loads at faster speeds and over longer distances than the B-18.

The B-17 was the obvious replacement for the outdated bomber, but at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, it was the B-18 that sat on the runways of most American bases.

During the initial Japanese onslaught, American forces were ill-prepared for combat. It is said many, if not most, B-18 bombers stationed in Hawaii and Philippines were destroyed on the ground.

Two U.S. Army Air Corps B-18 bombers make a simulated attack run on infantry caught in the open during training maneuvers in the Philippines, July 1941. Image: U.S. Navy

Remaining B-18 bombers were split across multiple duties. In Hawaii and Alaska, they were used for armed reconnaissance patrols. In May of 1942, they joined the U.S. Navy in searching for the Japanese fleet approaching Midway. They were also used as transports to ferry troops throughout the Pacific.

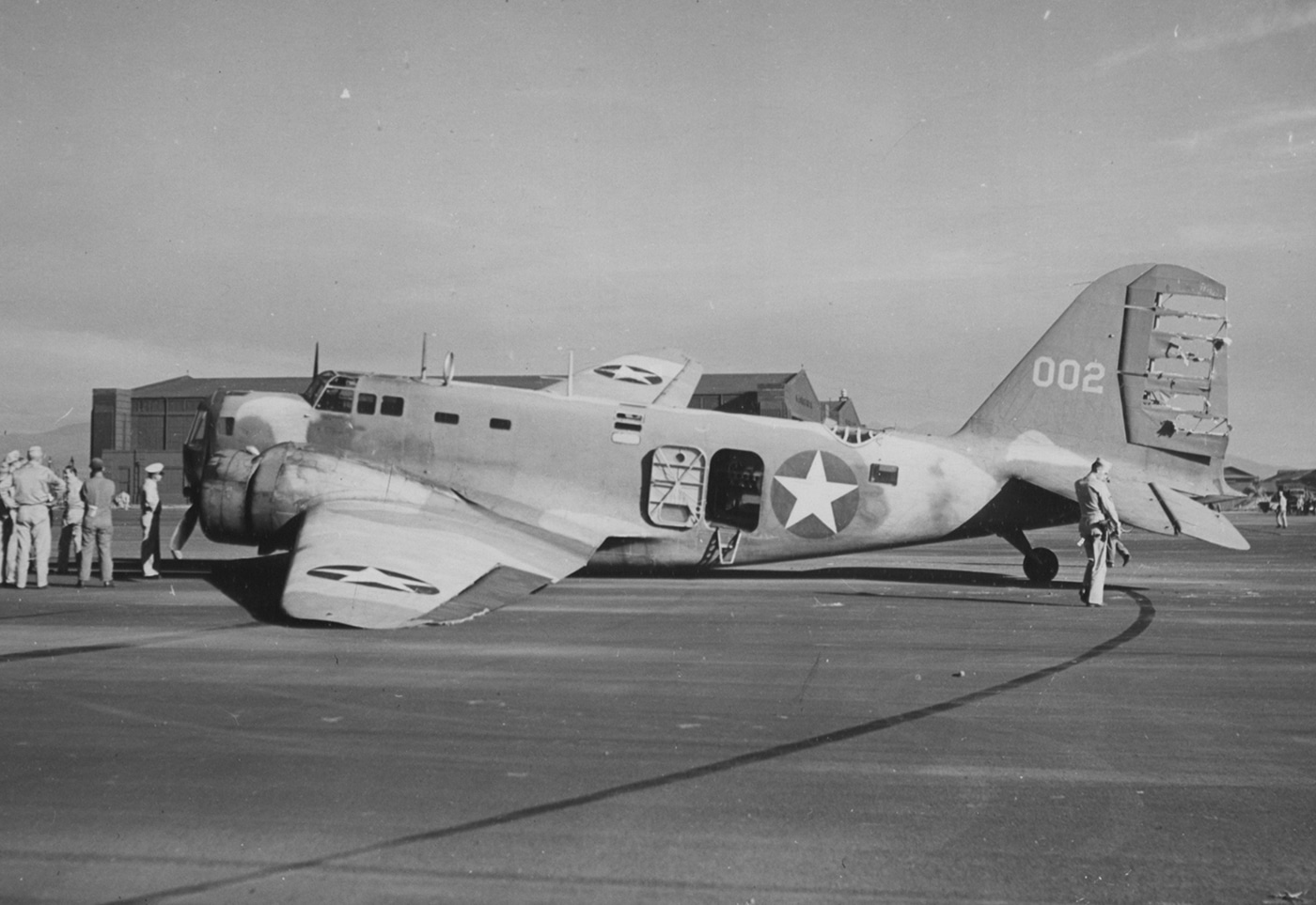

A damaged B-18 sits on Hickam Field during the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941. A large plume of smoke from the USS Arizona (BB-39) is visible behind the hangars. Image: Sgt. Lee R. Embree/U.S. Army

In a bit of an odd twist, the B-18 got a new lease on life from a general that tried to kill the project just a few years earlier.

Lt. Gen. Frank Maxwell Andrews was in charge of the Caribbean Defense Command, and he had a problem: German U-boats. With much of the U.S. Navy deployed to the Pacific Theater, the British Royal Navy was heavily relied on for anti-submarine efforts in the Atlantic. Unfortunately too many German subs were slipping past and threatening shipping off of the U.S. coast.

This B-18A Bolo fires rocket-powered depth charges at a target to its rear. Later “B” models would have a radar system that dominated the plane’s nose. Image: U.S. Navy

Lt. Gen. Andrews knew the strengths and weaknesses of the B-18 platform as he had been an outspoken advocate for the adoption of the Boeing B-17 over the B-18 several years prior. With more B-17 and Consolidated B-24 bombers coming online, Lt. Gen. Andrews was able to collect many of the remaining B-18 bombers and have them upgraded for anti-submarine warfare (ASW).

[Interested in other ways America fought the German U-boats? Read about how these WW2 blimps took on the Nazi submarines.]

Designated the B-18B, the new bombers were upgraded -18s and -18As that used radar to scan the ocean’s surface for German underwater boats. Additionally, many of the B-18B bombers were fitted with magnetic anomaly detection gear to locate submerged German boats. Bombs were replaced with depth charges.

This is a B-18B bomber with a radar array (nose) and MAD gear (sponson aft of the tail) for submarine hunting. It was converted from an “A” model for its new mission. Image: NARA

Between 1942 and 1943, B-18B Bolos flew regular ASW patrols over the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. The crews prosecuted multiple contacts and were credited with sinking four U-boats: U-512, U-520, U-615, and U-654.

[Read about Hitler’s nuclear U-boat in this article about the U-234 submarine.]

After World War II, surviving B-18 bombers were sold to the public. This plane found a new career in Oregon, spraying 1,000 gallons of DDT pesticide in each run. Image: NARA

In 1943, B-24 Liberators began replacing the B-18 for sub hunting duties. As the war wound down, the B-18s continued to be used as transports and training planes. After the war, they were surplussed and used for a range of things including crop dusting and fire fighting.

The United States was the primary user of the B-18. It’s impact in the Second World War are described above. However, two additional countries also used the B-18: Brazil and Canada.

A Royal Canadian Air Force Douglas Digby bomber flies over Nova Scotia in July 1941. Canada purchased 20 B-18A bombers from the United States. Image: Dept. of National Defence

The Royal Canadian Air Force acquired 20 B-18A bombers and designated them the Douglas Digby Mark I. They were assigned to No. 10 Squadron to replace the aging Westland Wapitis biplanes. Based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the Digby Mk. 1 was used to carry out about a dozen attacks on German submarines.

The Royal Canadian Air Force No. 10 Squadron based in Halifax replaced its bi-planes with the Douglas Digby. Image: Dept. of National Defence

Reports vary on exactly how many, but Brazil acquired either two or three B-18 bombers from the United States. It is believed two were B-18C variants. The possible third model is undetermined. They were part of the Brazilian Air Force 1st Bomber Group.

As with most military airplanes, there were a number of model variations in the B-18 bomber line. Roughly 130-135 of the original Douglas B-18 planes were manufactured. A single DB-18M was made that was designed as a trainer. It was essentially the same plane, but with the bomb gear removed.

This original B-18 crash landed at Hickam Field on May 22, 1943. The bullnose indicates this is a pre “A” model. Image: NARA

The last DB-18 was made as a prototype designated as DB-2 by Douglas. This bomber used a powered nose turret for advanced air defense.

The DB-18A was the most produced version of the aircraft with 217 examples delivered to the U.S. Army Air Corps. It was a welcome upgrade to the original, sporting more powerful engines that shortened take-off distances and improved the maximum air speed.

The Douglas B-18A model used the Wright R-1820-53 radial engine rated at 1,000 horsepower. It had nine cylinders and was normally aspirated. Wright R-1820 Cyclone engines powered many aircraft of the era including the Boeing B-17, Douglas SBD Dauntless and various versions of the Douglas C-47 Skytrain. Believe it or not, but Caterpillar actually modified these engines to run on diesel and used them to power the M4A6 Sherman tank.

This United States Army Air Corps unit photograph was taken in front of a Douglas B-18A Bolo. The updated bombardier position is visible through the upper nose. Image: Museum of Flight/Public Domain

Another change to the Douglas B-18A Bolo was the relocation of the bombardier’s station. This is immediately visible to the casual observer as the plane’s nose was significantly altered. Original B-18 bombers had a flat-ish glassed nose. The B-18A’s nose became markedly more pronounced which allowed the bombardier to be out over the nose gun position.

The plane’s development was ahead of the great bombing campaigns in Europe, so many of the theories regarding bombers were untested. Moving the bombardier’s location in the plane was not, on the whole, an unreasonable modification to a plane’s evolution.

A trainer with the bomb gear removed was also made for the U.S. Army Air Force. It was designated as the B-18AM.

Here are the specs of a standard B-18A bomber:

- Crew: Six

- Length: 57′ 10″ (17.63 m)

- Wingspan: 89′ 6″ (27.28 m)

- Height: 15′ 2″ (4.62 m)

- Wing Area: 959 sq. ft. (89.1 m2)

- Empty Weight: 16,320 lb (7,403 kg)

- Gross Weight: 24,000 lb (10,886 kg)

- Max Takeoff Weight: 27,673 lb (12,552 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Wright R-1820-53 Cyclone 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engines, 1,000 hp (750 kW) each

- Propellers: Three-bladed fully-feathering Hamilton Standard Hydromatic propeller

- Maximum Speed: 216 mph (348 km/h, 188 kn) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

- Cruise Speed: 167 mph (269 km/h, 145 kn)

- Range: 900 mi (1,400 km, 780 nmi)

- Service Ceiling: 23,900 ft (7,300 m)

- Guns: 3 × 0.30 in (7.62 mm) machine guns

- Bombs: 2,000 lb (910 kg) normal; 4,400 lb (2,000 kg) maximum

Completely replaced by the B-17 in 1942, the remaining B-18 and B-18A Bolos had no clear role for the United States. To make use of them, the USAAF had 122 of the planes — nearly all that remained — converted to anti-submarine aircraft. These conversion planes were renamed to the B-18B.

The “new” B-18B planes were fitted with radar and MAD gear.

To make room for the SCR-517-T-4 air-to-surface vessel radar, the bombardier’s position in the nose was replaced with a large radome. This helped the plane’s crew spot any subs operating on the surface. Keep in mind that submarines and U-boats of this era were all diesel-powered, and had to spend the majority of its time at sea on the ocean’s surface.

MAD gear was used for pinpointing the location of a sub underwater. MAD stands for magnetic anomaly detector (or detection depending on the context.) This sensitive equipment could detect the disruption in the earth’s magnetic field caused by a large metal submarine. Crews could fly over an area in a search pattern and plot the speed and direction of subs using multiple passes. This information would then be used to fire rocket-propelled depth charges from the bomb bay to sink the sub.

MAD gear is completely passive, so there was no way the submarines could detect its use. Of course the shadow of a passing plane combined with the noise of its engines were a pretty good tip for subs on or near the surface.

Here are the specs for the B-18B Bolo:

- Crew: Six

- Length: 57′ 10″ (17.63 m)

- Wingspan: 89′ 6″ (27.28 m)

- Height: 15′ 2″ (4.62 m)

- Wing Area: 959 sq. ft. (89.1 m2)

- Empty Weight: 16,320 lb (7,403 kg)

- Gross Weight: 24,000 lb (10,886 kg)

- Max Takeoff Weight: 27,673 lb (12,552 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Wright R-1820-53 Cyclone 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engines, 1,000 hp (750 kW) each

- Propellers: Three-bladed fully-feathering Hamilton Standard Hydromatic propeller

- Maximum Speed: 216 mph (348 km/h, 188 kn) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

- Cruise Speed: 167 mph (269 km/h, 145 kn)

- Range: 900 mi (1,400 km, 780 nmi)

- Service Ceiling: 23,900 ft (7,300 m)

- Guns: 3 × 0.30 in (7.62 mm) machine guns

- Bombs: Rear-firing, rocket-propelled depth charges

Only two B-18C Bolos were made. Like the B-18Bs, these were designed for anti-submarine duty. The major change on these models was the addition of a pair of forward-facing Browning .50-caliber machine guns. These models were eventually sold to Brazil. Their final disposition is unknown. They are unlikely to have survived the past 7+ decades.

Relatively few B-18 Bolos have been restored and are preserved for history. Excluding unrecovered B-18 wrecks or scrap, the following planes can still be seen today.

B-18: A single B-18 can be seen at the Castle Air Museum in Atwater, California. Tail number N52056 (originally NC52056) was used for fighting fires after World War II.

B-18A: Three B-18A Bolos are available for viewing. The first, tail number N56947, is located at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. Located in Dayton, Ohio at Wright-Patterson AFB, this is a must-visit museum for any aviation enthusiast.

A second B-18A is in the collection at Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum in Denver, Colorado. This example was sold as surplus after WWII, eventually ending up in Cuban hands. Federal agents, however, seized the plane in Florida when it was caught running guns to Fidel Castro. It eventually went to the National Museum of the United States Air Force before being transferred to Wings Over the Rockies.

The third B-18A is tail number N67947 which is currently at the McChord Air Museum. Located at McChord Field (formerly McChord AFB) near Lakewood, Washington, the museum is accessible to the public. This plane is believed to be the last Bolo to have flown — it’s final flight was in 1971. At the time of this writing, McChord Air Museum states the plane is “currently undergoing an extensive restoration.”

B-18B: One Douglas B-18B is believed to have been restored and can be viewed at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona. It still has a search radar dome in the nose, making it unique.