The German bombers of 1940 had been designed as a support aircraft — ready to attack key targets in the enemy’s rear areas. “Strategic bombing” was not an important part of the Luftwaffe strategy nor its preparation. Smaller twin-engine bombers like the Dornier Do 17 and the Junkers Ju 88 could be produced in greater numbers, faster, and more economically. They could also serve multiple roles compared to massive heavy bombers, and so the die was cast.

As for the bombers themselves, there were some hopes in the 1930s that the aircraft designs would be fast enough to avoid interception. That notion was put to rest during Germany’s Condor Legion operations during the Spanish Civil War. Polish and French air force fighters had also intercepted and downed German bombers during those short conflicts, but the Luftwaffe had not sent massed bomber formations against any previous foe.

The raids against England would be considered massive for the time, and the Germans still had reason to believe their bombers’ defensive guns could protect them against any Royal Air Force (RAF) fighters that managed to break through the Jagdwaffe fighter screen. This was flawed thinking as the Germans would soon learn — the RAF’s radar-guided interceptor formations were like nothing the Luftwaffe had ever experienced.

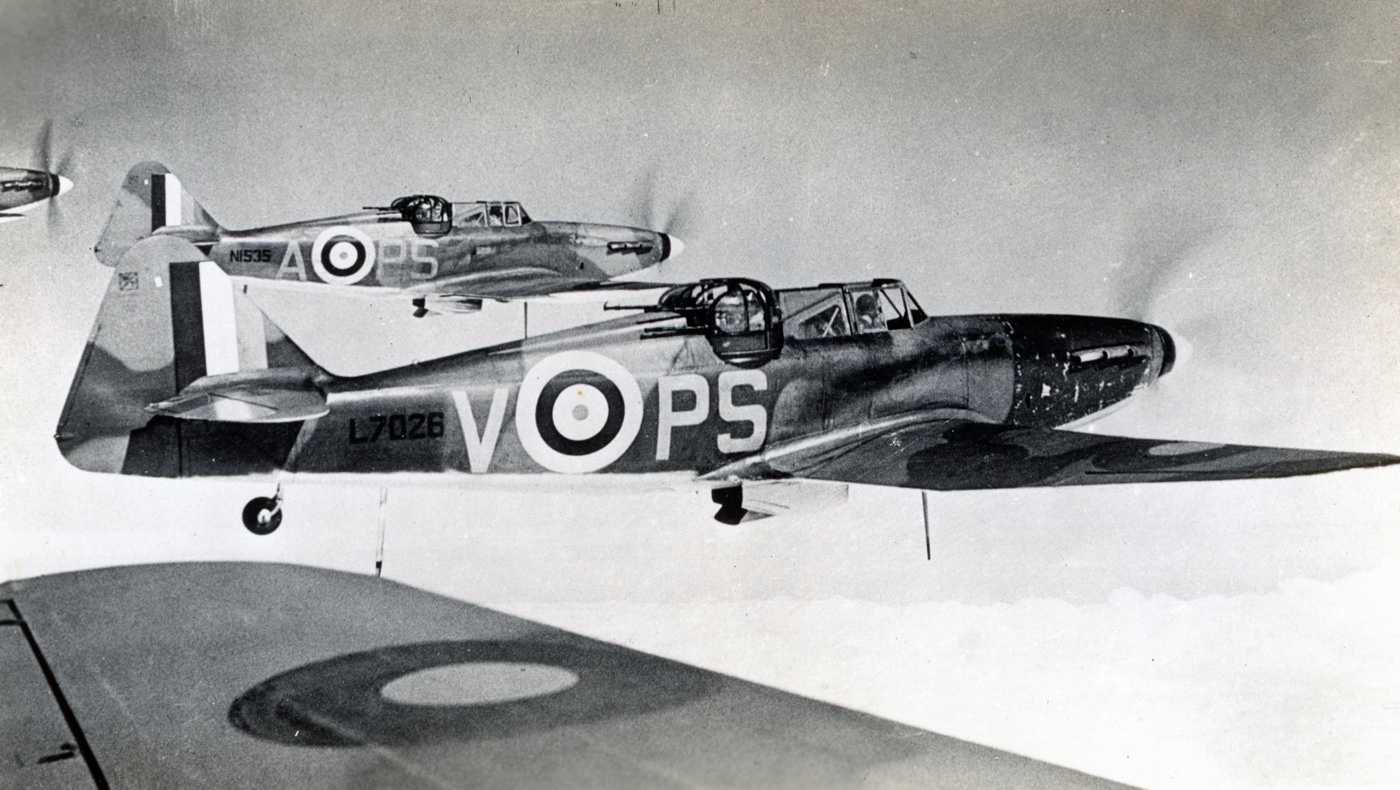

Even so, the Luftwaffe’s original attacks on RAF airfields in the summer of 1940 were working, and despite their losses, the German bomber force was beginning to break the RAF’s ability to defend England. But the Luftwaffe’s switch to bombing English cities allowed Fighter Command to recover, and their ensuing focus took a terrible toll on the German bomber force.

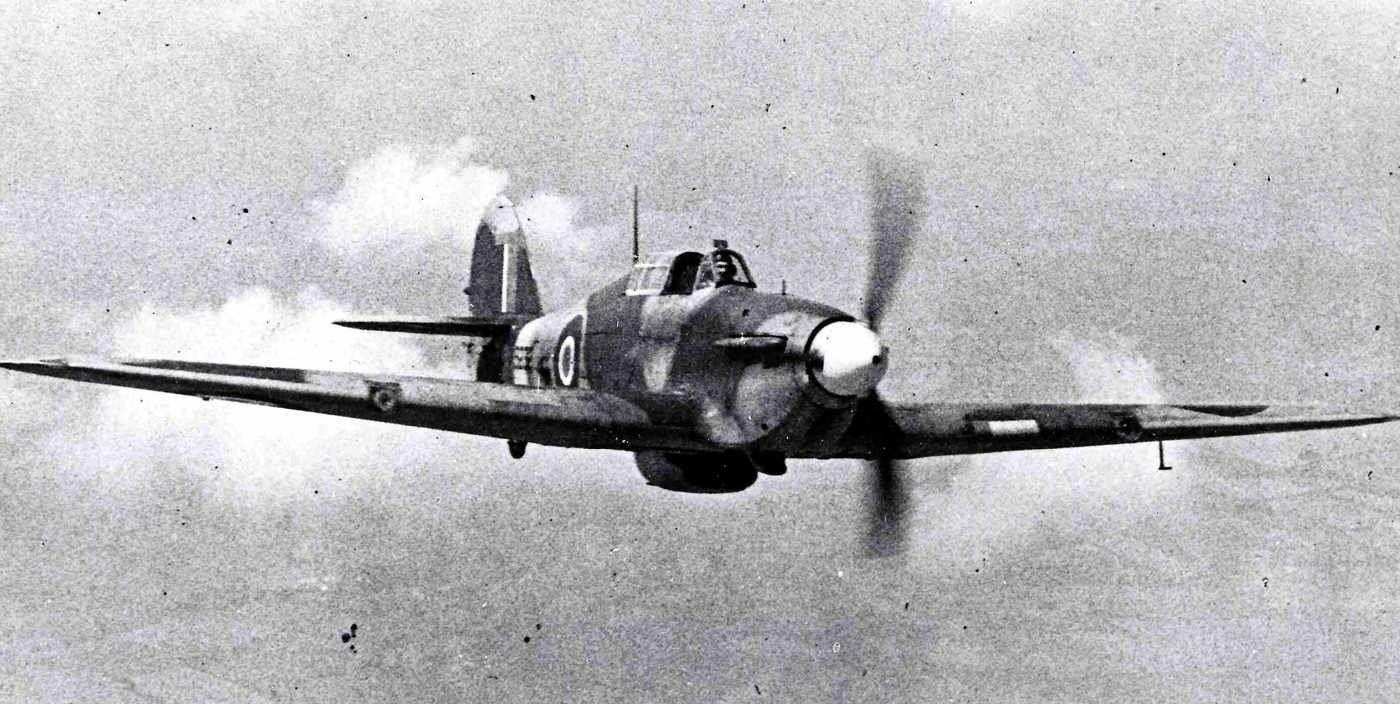

The Spitfire and Hurricane fighters carried the same armament — eight wing-mounted Browning .303 machine guns. In their battle against German bombers, it quickly became evident that the Browning .303 Mk II (1,150 rounds per minute) was most effective at less than 800 yards. Not only would RAF interceptors need to close the range to their target, but they would also need to find the most sensitive areas of the German bombers to knock them down.

RAF fighter pilots soon learned that the harrowing head-on attack was their best opportunity for a kill. Despite the 500-mph closing speed and the abbreviated firing time, the equation was simple for the attacker. One Hurricane pilot commented “Once you knew how, a head-on attack was a piece of cake. When you opened fire, you’d kill or wound the pilot and the co-pilot.”

In this case, the devil was in the details of the German bomber designs. All of the German twin-engine bombers involved in the battle featured a large glass nose for its pilot and navigator. For most of the German bombing campaign of 1940, Luftwaffe bombers normally had but a single MG 15 (7.92mm) defending the front of the aircraft. Even though the RAF fighters carried rifle-caliber Browning .303 caliber wing guns, eight versus one equals a tremendous firepower advantage. Sending hits crashing through the glass nose of a bomber tended to bring about the kind of crew casualties that knocked a Junkers, Heinkel, or Dornier out of the fight, and often sent it crashing to Earth.

In 1939, the RAF conducted a series of tests using .303 and 7.92mm ammunition against a Blenheim light bomber’s fuselage and the rear gunner’s 4mm armor plate. The first test used armor-piercing ammunition and the results were notably poor. Fired from a range of 200 yards, just 6% of the .303 AP rounds penetrated, while a paltry 1% of the 7.92mm AP broke through.

In the incendiary ammunition tests against the Blenheim’s self-sealing fuel tanks, both the standard British .303 MkIV incendiary-tracer and the German 7.92 incendiary rounds ignited the fuel tanks with one out of 10 shots fired. However, the RAF also tested the new Mk VI “De Wilde” incendiary, containing .5 grams of SR 365, which ignited on impact with a brilliant flash. Not only did the De Wilde rounds provide pilots with a welcome indication of a hit, they were twice as effective in igniting the fuel tanks.

The MK VI was tested operationally over Dunkirk and was quickly ranked as the most desirable of all the .303 ammunition. By the time German bombers were raiding England, the MK VI was in regular service, but in short supply.

In the Battle of Britain, a standard ammunition load for an eight-gun British fighter was: three guns loaded with standard ball, two with AP, two with Mark IV incendiary-tracer, and one with the Mk VI De Wilde incendiary. By late 1941, the load had been simplified to half AP and half incendiary.

A great flyer may not be a good shooter. A talented marksman might not be an exceptional pilot. But an aggressive man in the cockpit with an aptitude for aerial gunnery is probably an ace.

During World War I, the key issue for an aircraft’s forward-firing guns was “synchronization”, the ability to fire safely through the propeller blades. In World War II, an important issue (particularly for the RAF), was “harmonization”, the set convergence point for wing guns.

In 1939, RAF Fighter Command used “The Dowding Spread”, a convergence point of 400 yards. This wide dispersion of bullets was thought to provide an inexperienced pilot (or a poor shooter) with more hits on a twin-engine bomber.

Unfortunately for RAF fighter pilots, this was a highly optimistic appraisal of the .303 ammunition’s effectiveness. The construction of the average German bomber was barely affected by a few hits at 400 yards range — there were multiple Heinkel and Junkers bombers that absorbed more than a hundred hits from .303-caliber MGs and still made it home.

It soon became apparent that the Spitfires and Hurricanes needed to close on their targets and deliver a devastating burst of MG fire from their eight wing-mounted machine guns at short range. The convergence point dropped to 350 yards, and then to 250 yards.

Harmonization was to be found in close, and more German bombers were killed in a point-blank gunfight in British skies — RAF success rates rose from 39% to 53% with a 250-yard convergence setting. Closing the range dramatically increased the amount of hits, as well as the damaged caused by those that struck home.

The Polish pilots of No. 303 (Kosciusko) Squadron RAF were noted to press attacks in their Hurricane fighters to within 100 yards, consequently becoming one of the highest-scoring squadrons of the entire campaign.

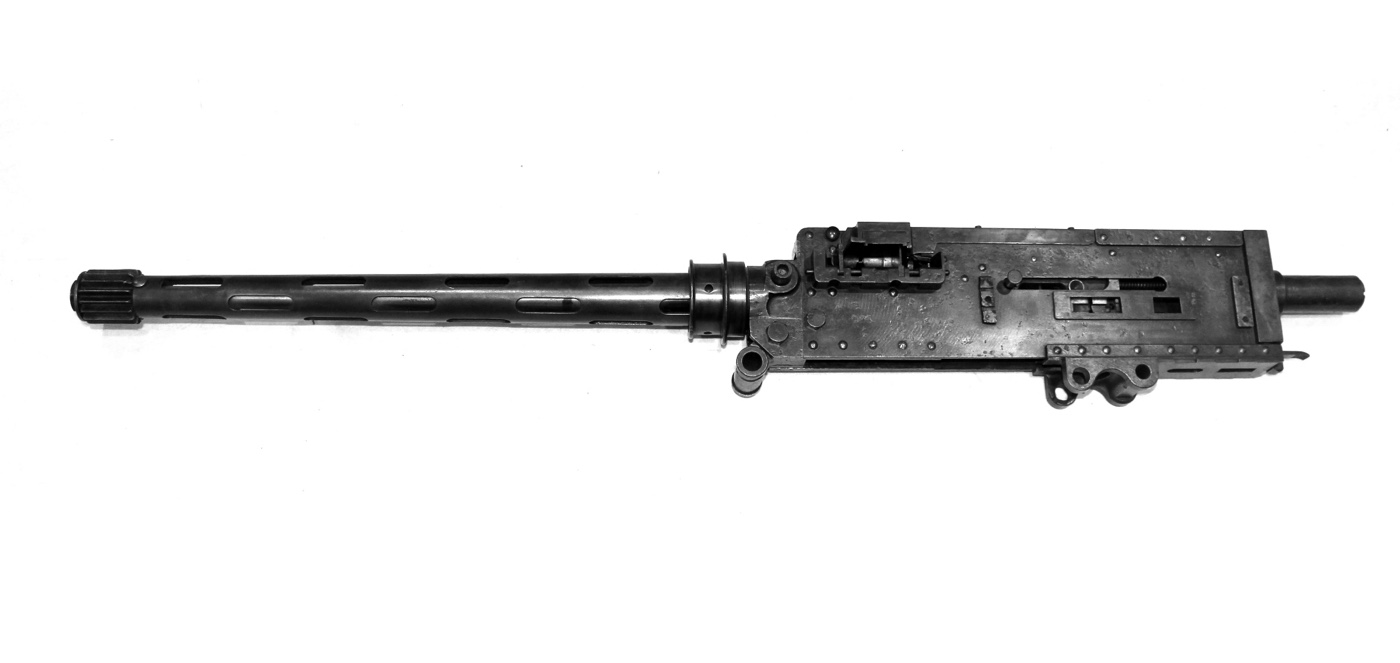

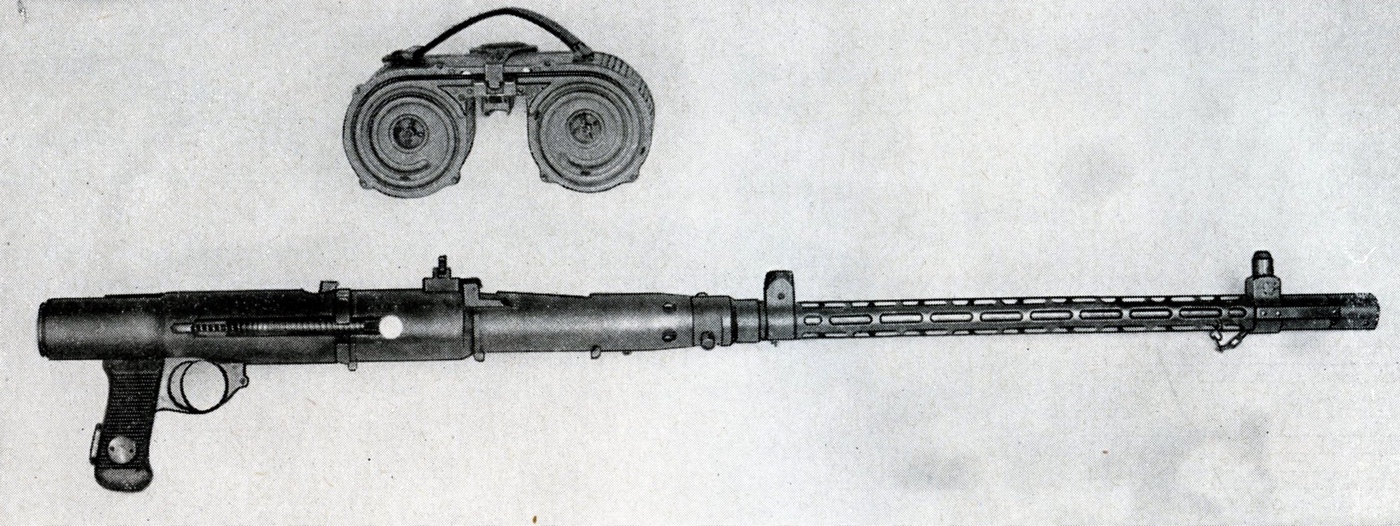

The primary defensive gun of German bombers in the Battle of Britain was the Rheinmetall MG-15 (7.92mm) fitted to the aircraft in “flexible” mounts. It is important to note that the MG 15 was not belt-fed, but rather the ammunition was fed from a twin-drum magazine that held a total of 75 rounds.

The left- and right-hand drums emptied alternately so that the gun’s center of gravity was not disturbed. A leather strap was placed across the top of the magazine to allow the gunner to reload quickly with one hand. Extra magazines were carried next to each gun position, but the 75-round drum capacity severely limited the MG 15’s extended firing capability.

Most MG 15 positions had a flexible tube that emptied the spent casings into a “catch bag”. Even though it was only a 7.92mm weapon, a loaded MG 15 with a cartridge bag weighed 27 pounds.

Even the most experienced gunner’s ability to reload his weapon quickly enough to respond to fast-moving enemy interceptors proved problematic. Luftwaffe air gunners operated in a cramped environment while wearing cumbersome flight suits. Firing at 1,000 rounds per minute, the MG 15 would drain its ammo load in less than five seconds — in the time it took to reload, the approaching enemy fighter could fire undisturbed.

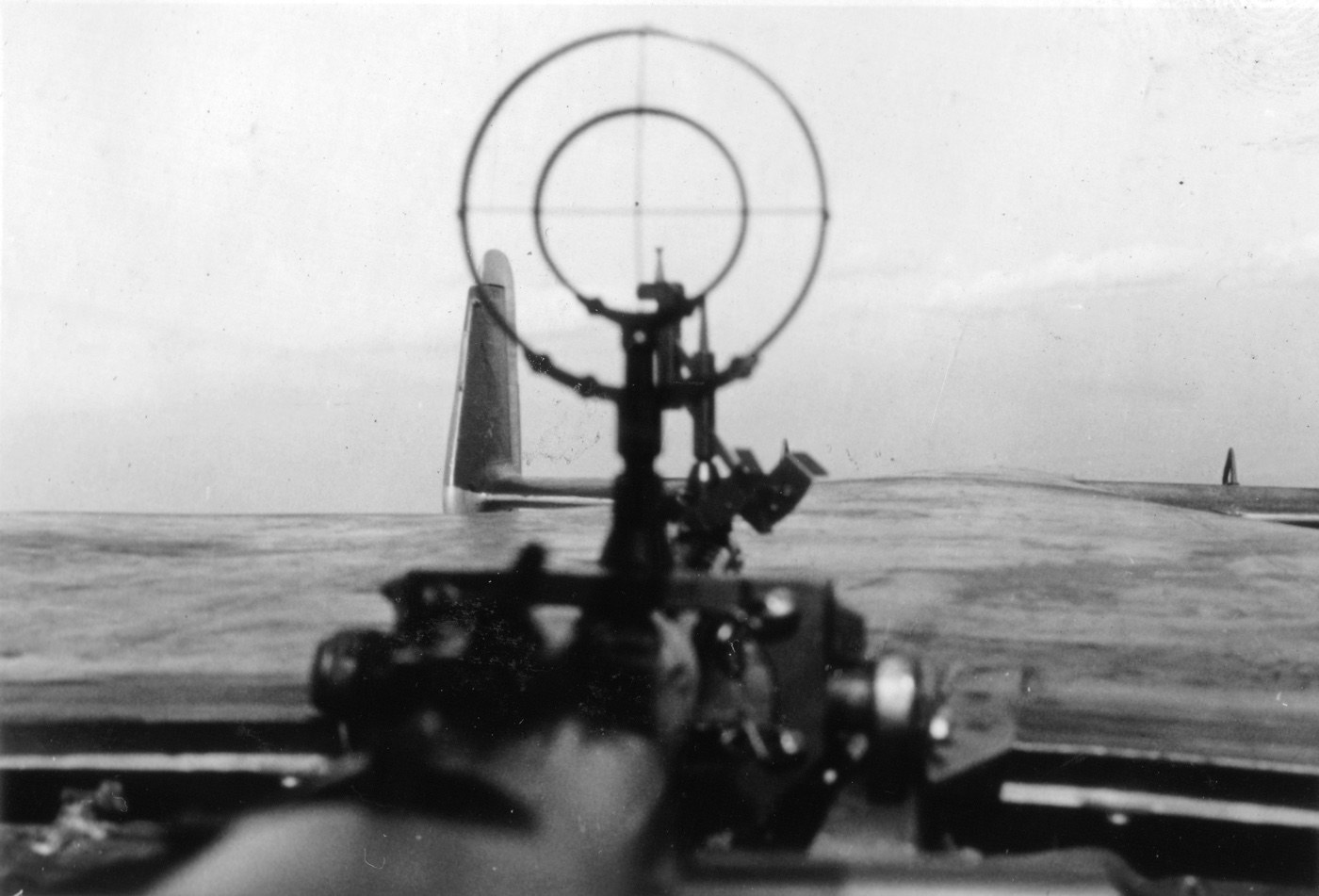

The ring sights for the MG 15 were adequate, but these were normally mounted on the portion of the barrel outside the aircraft — the gunner looking through the glass first and then the gunsight. Since both the RAF interceptors and German bombers used .30 caliber weapons, neither side had a firepower advantage, but German gunners had no “stand-off” ability with the MG 15, as it did not have the range or striking power to keep the Hurricanes or Spitfires at bay. The arrangement of the German bombers’ defensive armament was less than optimal as well. Regardless of the Luftwaffe bomber type, RAF interceptors were never deterred by “massed defensive fire”.

Inside the German bombers, there was little armor protection for the MG 15 gunners. Casualties among Luftwaffe aircrew were high, with more than 3,200 killed and wounded from July through October 1940. Germany’s bomber force never really recovered from its losses of experienced pilots and crews. As with all WWII air forces, training aerial gunners was time-consuming and expensive, and it was never a point of focus for the Luftwaffe.

MG 15s were used as defensive guns on Dornier Do 17s, Junkers Ju 88s, Heinkel He 111s, Focke-Wulf Fw 200s, Heinkel He 115s, as well as the rear-seat gunner positions of the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers and the Messerschmidt Bf110 heavy fighter. When the MG 15 was phased out as a Luftwaffe flexible defensive gun, the weapon transitioned into an infantry MG used in reasonable numbers in the last three years of the war.

Aboard the Heinkel He 111, Germany’s workhorse bomber in the Battle of Britain, the original amount of MG 15 defensive guns was increased from three (nose, dorsal, and ventral) to six — adding two MG 15s to fire from the fuselage side windows, and one to the front of the belly gondola. Some crews added an additional MG 15 to fire upward/forward from the glass nose.

Beginning with the He 111H-3, a single belt-fed “fixed” MG 17 was installed in the tail cone of some Heinkel bombers. This gun, ostensibly “aimed” by the pilot using a tiny rear-view mirror, could not move at all. The best result that could be hoped for was that a stream of tracers coming from the tail of the bomber would startle an attacking pilot, spoiling his aim or convincing him to break off his attack.

Despite their lack of defensive armament, the overall construction of the He 111 and the Ju 88 bombers provided a measure of resistance to the .303 machine guns of RAF fighters — and the Junkers and Heinkel bombers had vulcanized rubber protection for their fuel tanks.

Meanwhile, the slender Dornier Do 17 was always vulnerable, and even though some crews mounted as many as eight MG 15s around the crew compartment, there were only two gunners available to use them. After heavy losses in daylight raids, the Dornier bombers soon began to disappear from English skies.

Even before the Battle of Britain, the RAF wanted the destructive power of the 20mm cannon mounted in their fighters. Unfortunately, the Hispano cannon was not available in time to serve during the daylight battle. During the winter of 1941, as the Luftwaffe transitioned to night raids against British cities, the Bristol Beaufighter began to prowl the night skies.

The Beaufighters were equipped with a rudimentary radar unit, and just as importantly they carried four centrally mounted 20mm Hispano cannons (fed by 60-round drums, changed manually by the radar operator), as well as six .303 Browning MGs in the wings. A well-placed burst from a Beaufighter’s cannon battery was enough to explode a German bomber. As more Beaufighters became available and their airborne-intercept radar improved, losses among the Luftwaffe night bomber force increased significantly.