Junkers Ju 88 North Africa Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-417-1766-03A / Ellerbrock (CC BY-SA)

The Junkers Ju 88 was a two-engined medium bomber plane used by the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) throughout the Second World War (1939-45). Ju 88s were involved in the Battle of Britain and London Blitz as bombers, but this versatile aircraft saw action in many other theatres of the war, primarily as a dive bomber and a night fighter.

Design Development

After much debate between the German high command and the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the Luftwaffe bomber command (Kampfwaffe) was obliged to adopt the position that bombers should primarily be used strategically to assist ground troops. This meant that unlike, say, the British Royal Air Force, the Luftwaffe concentrated not on heavy bombers but building squadrons of more versatile medium bombers.

In August 1935, aeronautical companies were invited to provide an answer to the German Air Force’s requirement for a two-engined, medium-sized and high-speed bomber (Schnellbomber). Junkers came up with the Junkers 88, with various prototypes given a V designation plus a number 1 to 5. The first prototype, the Ju 88 V1, flew in December 1936 and impressed with its high speed. By March, the Ju 88 V5 was capable of speeds of over 300 mph (500 km/h) and so broke several records.

The upside of its checkered design history was that the 1940 version of the Ju 88 was more versatile than originally planned.

The decision in 1937 to give the Ju 88 a dive-bombing capability meant that the design process now became fraught with delays and constant revisions. As the historian J. Holland notes, “some 25,000 changes were made to the original design” (216). Most significant of these changes, perhaps, was the strengthening of the wings to take the force which resulted from steep dives, the addition of brakes to arrest the plane at the nadir of the dive, and the lengthening of the fuselage to admit extra crew members. The consequence of all this was that the plane ended up being much heavier and slower than the original plan, a situation that led Field Marshall Erhard Milch (1892-1972), one of the founders of the Luftwaffe, to disparagingly describe the Ju 88 as a “flying barn door” (ibid). The problems of weight and speed were partially alleviated by adding rocket boosters for takeoff when carrying heavier bomb loads. The design changes kept on coming, too, notably an increase in the wingspan. As a result of the complex design, the Ju 88 took more time to build than many other aircraft types.

Junkers Ju 88 Factory Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1976-097-22 (CC BY-SA)

Introduced into Luftwaffe service in September 1939, just as WWII started, the Ju 88s’ challengers as the medium bomber of choice within the Luftwaffe were the antiquated and poorly armed Dornier Do 17, the equally vulnerable but faster Dornier Do 215, and the tried and tested Heinkel He 111, which was overall the best of the three at the beginning of the war. The Junkers Ju 88 was smaller than the other three medium bombers but faster than the He 111 and the Do 17, and yet it was capable of carrying as heavy a bomb load as the He 111. As a consequence, gradually the Ju 88 took over from the He 111 as the bomber of choice but both saw service right through the war. All of these planes had two engines, which fundamentally restricted their bomb loads and range compared to Allied heavy bombers like the B-17 Flying Fortress and Avro Lancaster bomber.

From 1941, the Ju 88 began to be deployed more as a dive-bomber than a level-bomber.

The upside of its checkered design history was that the 1940 version of the Ju 88 was more versatile than originally planned, making it perhaps the most versatile of any aircraft of any air force in WWII. The Ju 88 could perform as a bomber, dive-bomber, and night fighter. Other duties performed by the Ju 88 included long-range reconnaissance (when they were fitted with extra fuel tanks, radar, and cameras), attacking shipping, and minelaying at sea. Finally, one distinct advantage of the Ju 88 was that its frame was built in such a way that it could withstand tremendous punishment from enemy fire. Factories dedicated to Ju 88 production included those at Brünn (now Brno in the Czech Republic) and Graz and Vienna in Austria. Air forces which operated Ju 88s besides the Luftwaffe included the Finnish, French, Hungarian, Italian, and Romanian.

Specifications

The Ju 88 had a wingspan of 65 ft 7.5 in (20 m) and a length of just over 47 feet (14.4 m). The Ju 88 had, in ideal conditions, a top speed of 292 mph (470 km/h), but with a bomb load, 230 mph (370 km/h) was a more typical speed. The bomber had a maximum range of 1,700 miles (2,730 km), although its more typical combat radius was 360 miles (580 km). It was powered by two 12-cylinder Junkers Jumo 211 engines, the best versions of which gave 1,350 hp (1007 kW) each. Some later models, to keep up with developments in enemy fighters, had more powerful BMW radial engines fitted, but there were not as many of these available as the Luftwaffe wished. The aircraft’s service ceiling was 26,900 feet (8,200 m).

Ju 88 Rear Cockpit Machine Guns Siedel (Public Domain)

The Ju 88 could carry a bomb load of up to 5,500 lbs (2,500 kg), but more common was a 4,400-lb (2,000 kg) load. Besides using the bomb bay within the undercarriage, bombs of various types, including torpedoes, could be attached to cradles under each wing. Defensive armaments varied, but the best version had six MG15 machine guns: one mounted in the nose, one in front of the pilot (which he could operate), two more behind him facing to the rear, and two under the plane below the cockpit, again facing the rear. These guns were typically 7.92 mm (0.31-in) calibre. Some models, especially those destined for a night-fighter role, were fitted with one or two 0.78-inch (20-mm) cannons in the nose, while 32 of the very last models had a 2-inch (50-mm) cannon, which could deliver some serious punch. The Ju 88 had a crew of four or five, although this could be fewer when performing night-fighter duties.

Navigational Aids

Bombing was a far from accurate operation for all sides in the early years of the Second World War. The Luftwaffe did employ various technological devices to assist navigators to reach their targets and bomb-sighters to drop the loads at the correct position. There were radio beacons spread across the European continent to aid navigation, although the British interfered with these by sending out masking signals known as Meacons.

Knickebein (‘Crooked Leg’) navigation beams were in operation from December 1939. These were two radio signal beams sent across and from Continental Europe (France, the Netherlands, and Norway) which the bombers could track. One beam sent out dot signals and the other longer dash signals. Where the two beams crossed marked the place where the bombs should be dropped. Thanks to military intelligence, the British knew of the system from the spring of 1940, and jamming of it began in August with a device code-named ‘Aspirin’ (since Knickebein was a real headache for the defenders).

Junkers Ju 88 Design Features UK Air Ministry (Public Domain)

Ju 88s and other bombers could be fitted with X-Gerät (X-apparatus) radar equipment, which followed several beams sent by transmitters in Continental Europe. X-Gerät was more accurate than Knickebein and allowed aircraft, by following the single beam sending out coarse signals (the others sent fine signals), to find their targets in cloudy weather or at night. Not all bombers were fitted with the system, but those which were – identifiable by their antennae along the plane’s dorsal – were used to mark the target for other planes to follow. The Germans called this guidance system Wotan I, after the Germanic name for Odin, the one-eyed god from Norse mythology. The British discovered the secret technology and created a way to jam the guidance system, using a device code-named ‘Bromide’, although it was not always successful.

The third and best Luftwaffe radar system, employed from November 1940, was Y-Gerät. In this system, a single beam was sent to a bomber which then returned it. The time taken indicated the exact position of the aircraft at any one moment. The system was code-named Wotan II. Y-Gerät could also be jammed by British-sent signals, this time using a system with the code name Domino.

Although the Allies eventually cottoned on to these technological aids, Ju 88s could fight back in the tech wars. Fitted with a Lichtenstein nose radar and with a Flensburg radar aerial on each wing, a Ju 88 became a very useful listening device that could detect Royal Air Force night bombers that were themselves using radar.

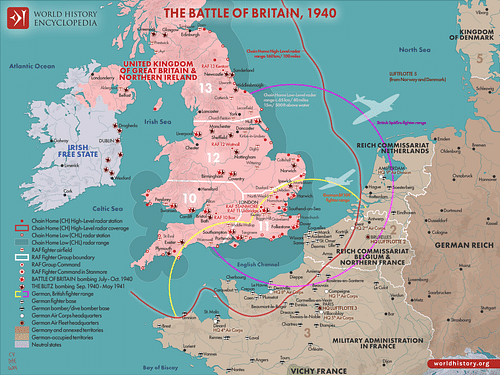

Map of the Battle of Britain, 1940 Simeon Netchev (CC BY-NC-SA)

Operations

Up to 1940, around 1,885 Ju 88s had been built, then around 2,000 were constructed each year in 1941, 1942, and 1943. Ju 88s were involved in both the Battle of Britain (1940), attacking airfields and strategic targets like radar stations, and the bombing campaign of British cities that followed, which included the London Blitz (1940-1). Through 1940, the Ju 88 usually performed as a level-bomber. When flying to and from targets in Britain, Ju 88s, despite their machine guns, proved to be vulnerable to attacks from considerably faster and more manoeuvrable enemy fighters like the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane. Consequently, like other Luftwaffe bombers, Ju 88 squadrons were protected by a fighter escort when possible, for example, a squadron of Messerschmitt BF 109s or, later in the war, Focke-Wulf FW 190s. The Ju 88 did fare better than other German bombers in encounters with fighters when it was on the home run since “it was quite manoeuvrable and, especially at low altitudes with no bomb load, it could nearly outrun a Spitfire” (Cawthorne, 189). Eventually, though, Ju 88s became so vulnerable to fighter attacks that their use was generally reduced to night activities.

As the war rolled on and the Allied bombing of Germany began in earnest, the Ju 88 became a useful night fighter to attack enemy bomber planes, as explained by the aviation historian R. Neillands:

These aircraft were slow, but speed is not all that important in a night fighter, provided it is fast enough to catch the bombers; far more important is the need to provide a steady gun platform for the cannon, and crew space for the Funker [radio operator]…They had the freedom to roam at will about the night skies, flying along with the bomber stream, using radar aids and ground control first to pick up the stream and then to find individual bombers.

Sometimes Ju 88s would fly in pairs during their night operations, with one plane a little ahead of the other and with their cockpit lights on. The second plane would have no lights, and so when enemy aircraft were attracted to the front Ju 88, the rear one could attack undetected. To make them less visible to the enemy, Ju 88 night fighters usually carried a dark camouflage and often had their national markings and squadron numbers painted over.

Junkers Ju 88 & Crew Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-359-2003-05 / Röder (CC BY-SA)

From 1941, the Ju 88 began to be deployed more as a dive-bomber than a level-bomber. The Ju 88 typically swooped on a target at a 45-degree angle and delivered its bombs with a high degree of accuracy. Some Ju 88s were fitted out with rockets for use as tank busters.

Another incarnation of the Ju 88 as a bomber was code-named ‘Beethoven’. The idea was to use otherwise inoperable Ju 88s as guided missiles. This was achieved by packing a Ju 88 with explosives and attaching a fighter plane to the top of it using struts. The fighter flew its cumbersome cargo close to the intended target and then released it to fly on in the general direction. These bizarre aircraft were called Ju 88 Mistel composites (Mistel being the German for the parasitic yet evergreen mistletoe). The first mission using the Mistels came in the summer of 1944 when a fleet of four Allied ships was attacked. All four targets were hit and damaged (although none sank). Around 250 Mistels were built, and bridges became a favourite target.

In other theatres of the war, where competition for the skies was not always so great as it had been over Britain, the standard Ju 88 excelled. The bomber was deployed in various Mediterranean campaigns such as Crete and Malta, and as part of the Afrika Korps in North Africa. Ju 88s flew in Italy and Romania, and on the Eastern Front against Russia. Throughout the war, 14,676 Ju 88s were built in all.