A popular idea in science fiction is the resurrection of prehistoric creatures such as dinosaurs, mammoths, and even Neanderthals. In reality, such a resurrection of a prehistoric creature has yet to be achieved, although there is currently an attempt to create a hybrid mammoth-elephant embryo by a Harvard team. A related topic popular among people who think about ancient beasts from remote epochs is the idea of discovering a relict population of an otherwise extinct species. Legends of the Mokèlé-mbèmbé in Africa and the Almas in the Caucasus Mountains are examples of mythical discoveries of such relict populations.

In the plant world, the botanical equivalent of discovering a living dinosaur has actually been made. A species of the Wollemi Pine tree, Wollemia nobilis, was discovered still living in a wilderness area west of Sydney, Australia. The tree is a member of a genus that first evolved over 200 million years ago. It is now in the process of being revived through the worldwide cultivation of the plant for gardening purposes.

Wollemi Pine, one of the oldest known tree species. Kew Gardens, London. (CC BY 2.0)

From Domination to Fossilization

Wollemi Pines evolved on Pangaea when all the continents were still joined during the early Mesozoic. Because of this, close relatives of the tree are found in Australia, South America and other parts of the Southern Hemisphere. For 100 million years, the Wollemi Pine tree was one of the dominant genera of trees in the Southern Hemisphere. Dramatic climate changes during the Neogene and Quaternary led to the dying out of most Wollemi Pine populations. Today, the only place where Wollemi Pines are still found alive in the wild, not as fossils is the Wollemi National Park in the Blue Mountains.

Wollemi National Park at Baerami along the Bylong Valley Road, NSW Australia (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Wollemi Wilderness

The Wollemi National Park is one of the most isolated and rugged areas in the world. Numerous canyons and gorges carpeted by thick rainforest make it very difficult to navigate. The canyons also create pocket ecological communities which can survive for millennia on end in relative isolation from the rest of the biosphere. It is probably for this reason that this Wollemi Pine species was preserved here.

The living Wollemi Pines were discovered in 1994 by an Australian botanist, David Noble, who was hiking through the area when he came across a peculiar tree with multiple trunks and strange bark that looked like bubbles of chocolate. He was familiar with paleobotany and it did not take him long to recognize the plant for what is was.

Wollemi Pine. Mount Tomah Botanic Garden. NSW (CC BY-SA 2.0)

A Distinctive Pine

The Wollemi Pine species is a member of the genus Wollemia, a genus of pine tree within the family Araucariaceae. Other genera in the family include Agathis and Araucaria, both of which have similarities to Wollemia. All three genera date to the early Mesozoic Era.

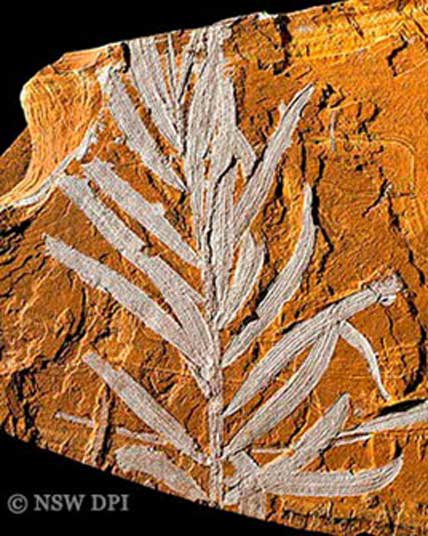

Agathis Jurassica, plant fossil from Talbragar. Related to the modern Wollemi Pine. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Wollemi Pine truly looks like a tree from another epoch. It grows multiple trunks and will shed them regularly. It is a gymnosperm plant like all trees from the Triassic. Angiosperm plants don’t appear in the fossil record until the Cretaceous. Because of the multiple trunks, it is difficult to count the total number of individual trees. So far, botanists have discovered a total of about 240-276 individuals, 40-76 adults and 200 juveniles. One massive individual tree actually has 160 separate trunks!

Two features of the plant that make it particularly distinctive are its unusual bark and the fact that it sheds entire branches instead of leaves. The plant has also been shown to be able to grow at temperatures as cold as -12 C and at least as hot as 45 C. The plant evolved in the hothouse world of the Mesozoic so it makes sense that it would be able to withstand very warm temperatures.

Kew Gardens Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis), London (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Protection and Revival

Since its discovery, the plant has been grown in captivity in several parts of the world. The original impetus for exporting the tree as a garden plant was to reduce any temptation on the part of people to steal trees or their seeds from the wild and thus endanger its local habitat with the threat of disease and invasive species. The other reason was to ensure that this fascinating botanic relict did not become extinct.

One of the first private companies given the rights to grow the trees was the Birkdale nursery. The Australian Department of Primary Industry was also one of the first organizations to be afforded the rights to grow the trees. Wollemi Pines are now for sale in by many vendors across the world.

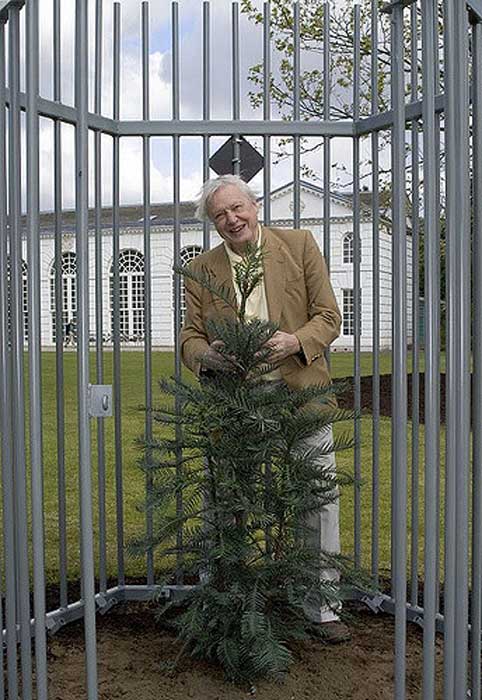

In 2005, Sir David Attenborough planted Kew Garden’s first Wollemi Pine (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Collecting the seeds from wild plants poses a danger to the Wollemi Pine species since it makes damage to the trees and introduction of disease and parasites from the outside world more likely. As a result, most specimens are grown vegetatively from young plants that have been grown in captivity from seeds collected from the original wild trees.

Places where the tree is now grown include but are not limited to Australia, the United States, and Japan. Their climatic limits are being tested to expand the market. Through this, an ancient tree’s dominance is being revived. The Mesozoic Era may be gone, but we can recreate part of it through encouraging the growth of living fossils like Wollemia nobilis.