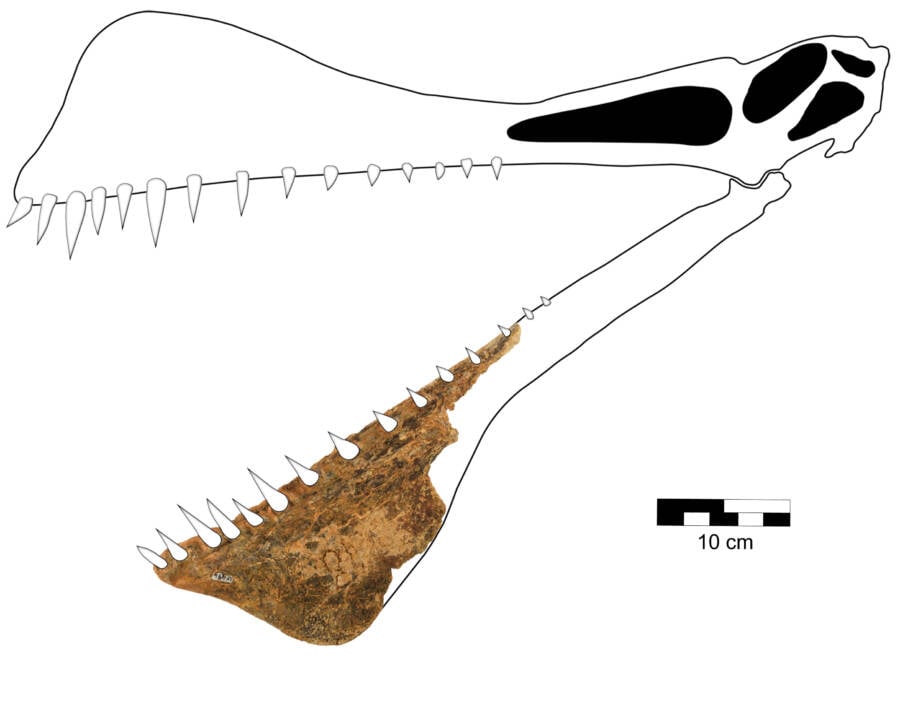

The giant flying reptile, called Thapunngaka shawi, was discovered in Queensland, Australia, and had a 30-foot wingspan and a head alone that measured three-feet long with 40 razor sharp teeth.

University of Queensland The Thapunngaka shawi just discovered by University of Queensland researchers was all wings, neck, and razor teeth.

Australia is home to man-eating sharks, giant spiders, and about 100 varieties of venomous snakes. About 105 million years ago, however, a far more terrifying predator hunted in the skies above — and researchers are comparing it to a “real-life dragon.”

Researchers at the University of Queensland this week announced the discovery of a new pterosaur, naming it Thapunngaka shawi.

With a wingspan of nearly 30 feet, a skull alone of around three feet, and 40 razor-sharp teeth filling a mouth like a “spear,” Thapunngaka shawi likely cast a fearsome shadow over the young dinosaurs and large fish of the prehistoric Eromanga Sea, which covered much of what is now the Outback.

“It was essentially just a skull with a long neck, bolted on a pair of long wings,” said University of Queensland Ph.D. candidate Tim Richards, who led the research team. “This thing would have been quite savage.”

It’s also one of just three pterosaurs of its kind ever found in Australia — and the biggest.

University of QueenslandResearcher Tim Richards, who led the team identifying the dinosaur, pictured with another pterosaur skull.

The creature’s fossilized jaw was initially found in 2011 by a local man named Len Shaw, who had been “scratching around” a quarry northwest of Richmond for years.

The researchers named the species after Shaw, while its genus, Thapunngaka, comes from a conjunction of the Indigenous Wanamara nation’s words for “spear” and “mouth” — making this fearsome new dinosaur’s name literally translate to “Shaw’s spear mouth.”

Not only is Thapunngaka shawi the largest pterosaur ever found in Australia, it’s likely among the most menacing aerial predators ever to live.

“It’s the closest thing we have to a real-life dragon,” Richards said.

The spot where Shaw found the Thapunngaka shawi jaw dates to the Cretaceous Period, between 145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago. That lines up with the heyday of pterosaurs, who roamed the skies from the late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous period.

The creature belonged to the Anhanguera family of pterosaurs, who once soared over every continent on Earth. But these pterosaurs’ skeletons were largely made up of hollow bones that, while aiding their ability to fly, were too delicate to leave behind many well-preserved fossils.

Tim Richards/University of QueenslandResearchers reconstructed the skull of Thapunngaka shawi using the fossilized jaw fragment and surmised that it sported great crests on the top and bottom of its head.

“It’s quite amazing fossils of these animals exist at all,” Richards said, adding that Thapunngaka shawi is the third species of Anhanguera found on the continent.

Thapunngaka shawi also sported bony crests on its upper and lower jaws, which Richards and fellow researcher Dr. Steve Salisbury believe made the prehistoric dragon particularly stealthy, allowing it to quietly swoop down on unsuspecting prey.

The team plans to use the new fossil to further study pterosaurs’ aerodynamics.

Richards and Salisbury’s discovery follows the 2019 find of the so-called “iron dragon” pterosaur — also found in Queensland, in the late-Cretaceous Winton Formation. Ferrodraco lentoni was a remarkably well-preserved fossil, and the most complete yet found of a pterosaur in Australia.

Discovered by a ranch grazier named Bob Elliott, that pterosaur of the Anhanguera genus was a similarly fearsome airborne predator, albeit with a wingspan about half the size of Thapunngaka shawi‘s.

Wikimedia CommonsA well-preserved Ferrodraco lentoni, or “iron dragon,” fossil was also found in Queensland in 2017.

Ferrodraco lentoni got its name from the way it fossilized. Researchers found that the carcass was filled with iron-rich fluids that eventually fortified the pterosaur’s notoriously thin bones, eventually making for an exceptional fossil.

While the University of Queensland researchers have only a fraction of the fossilized remains of Thapunngaka shawi in this case, even what little has been found makes it clear that this prehistoric dragon was a far more terrifying predator than the “iron dragon.”

Thapunngaka shawi also dwarfed the Mythunga camara, the early-Cretaceous pterosaur discovered in Australia back in 1991, which had a wingspan of less than 15 feet.

Richards stressed in his report just how frightening Thapunngaka shawi must have been all those millions of years ago for smaller creatures either on land or sea.

“It would have cast a great shadow over some quivering little dinosaurs who wouldn’t have heard them coming until it was too late.”