In the lethal world of air warfare, making yourself nearly invisible can be the difference between coming home … or being shot down.

- Stealth, or the ability to reduce one’s detectability by radar, has become a key aspect of aircraft design.

- Stealth involves carefully designing an aircraft to minimize the effectiveness of enemy radar.

- Brought to its logical conclusion, stealth can result in some unusual aircraft, such as the F-117A Nighthawk and the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

In the back-and-forth struggle to survive in the air, one of the most important features a warplane can have is a reduced radar cross-section, or stealth. In a world where detection is a matter of life and death, stealth is now a must-have feature for fighters and bombers.

Here, we break down how stealth works, and how air forces use it to defeat enemies—both in the air and on the ground.

Integrated Air Defenses

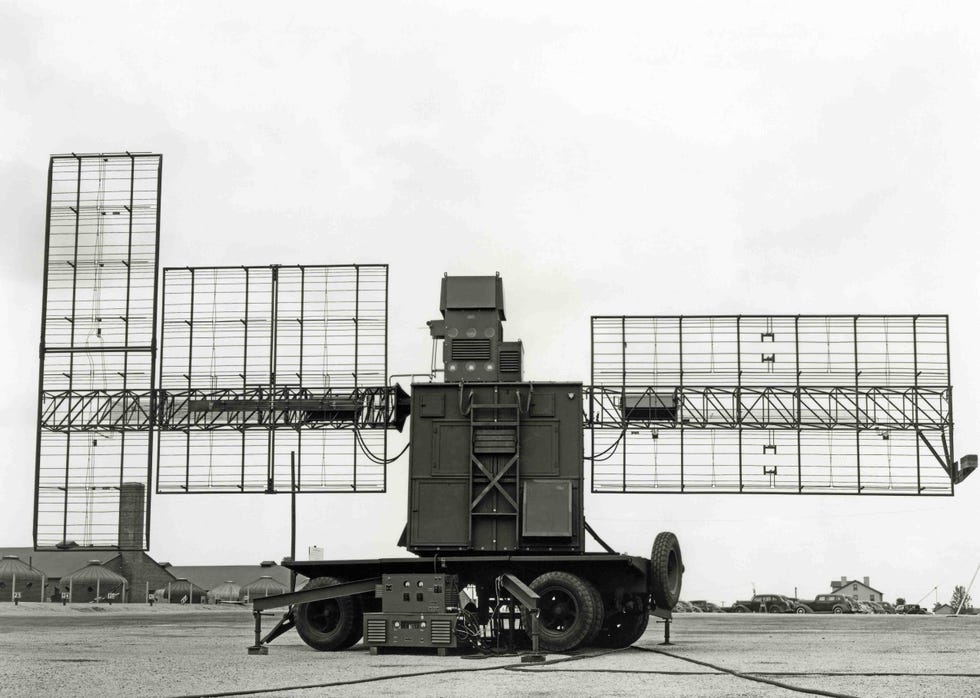

In the 1960s, countries around the world began investing in integrated air defenses. Ground- and air-based radars were tied into command-and-control systems, which in turn could give orders to surface-to-air missile batteries and air bases with fighter jets ready to take off. In Vietnam, the Middle East, and Western Europe, this tight integration promised to savage any attacking bomber force that attempted to get through.

As a result, offensive air power was forced to innovate new tactics—such as airborne command-and-control, electronic warfare, air-defense suppression, and more—all to ensure that relatively few aircraft were able to pierce the defenses and reach their targets. All of this put a lot of aircraft, and their pilots, at risk.

Radar was the foundation of air defense. It was (and still is) the primary means of aircraft detection. Radar can detect aircraft from 100 or more miles away, and while it can’t tell what kind of aircraft are flying, it can tell things such as relative size, speed, altitude, and heading; that’s enough to organize the air defense of a sector, posturing defending forces to repel an incoming attack.

All of this had military planners and aerospace engineers wondering: what if a plane could fly through enemy airspace without showing up on radar? Instead of a dozen or more planes all attacking one target, one plane—the plane carrying the bombs—could infiltrate the enemy’s complex defenses, deliver its ordnance, and fly home.

The Dawn of Stealth

Radar works by sending out streams of radio waves, and intercepting them when they return. Radio waves that strike objects in their path will be reflected back, giving defenders warning that intruders are en route. Engineers knew that radio waves act differently when striking different types of surfaces, but no one had worked out a method for predicting exactly how those waves responded ahead of time.

The implications of understanding how to build radar-evading planes were enormous. Engineers could design a 50,000-pound plane that was as visible to radar as a bumblebee, meaning it would have to be much closer to the radar system to even be detectable. If that reduced a plane’s vulnerability to radar detection from 100 to just 20 miles, stealth aircraft could carefully pick their way between radar systems undetected, and the enemy would be none the wiser.

In the 1960s, Soviet physicist Pyotr Ufimtsev developed a model for predicting how electromagnetic waves, such as radar waves, would scatter upon hitting 2D and 3D surfaces. Although published in the USSR, his work was never apparently considered for any practical application. That is, until defense contractor Lockheed noticed it and had his works translated into English; Ufimtsev’s work became the basis for modern-day stealth technology.

Lockheed exploited Ufimtsev’s work to the fullest, because it confirmed that special shaping could reduce an airplane’s radar signature. An airplane’s major surfaces—the nose, fuselage, wings, ailerons, flaps, cockpit canopy, and so on—could be analyzed, and then expressed, as what became known as a “radar cross-section.” Aircraft with large, flat surfaces, like the fuselage of the B-52 bomber, or vertical stabilizers like the F-111 tactical bomber reflected a large amount of radar energy. External stores, like bombs, missiles, and fuel tanks, also reflected energy. Attention to detail was required: intakes could actually focus radar energy, creating a sharper return, while even rivets, gaps, or the smallest protrusion could reflect energy.

Stealth Fighter and Bombers

The first aircraft designed specifically with stealth as a priority was Have Blue. Built by Lockheed Martin, it was unlike any other plane ever made. Unlike most aircraft, which had curves, vertical surfaces, and large, gaping inlets to gulp air, Have Blue was faceted, like a diamond, with angled surfaces, and had small inlets. Have Blue’s two vertical stabilizers did not stick straight up, but were instead angled toward one another so that they did not directly reflect back radar energy.

Have Blue was a technology demonstrator. Four years later, the first F-117A Nighthawk stealth fighter was produced and, unlike Have Blue, the F-117A was designed to fight. It was similar to Have Blue, but larger, designed to carry two 2,000-pound laser-guided bombs internally. Unlike Have Blue, it had two vertical stabilizers in a swallow-tail configuration, angled outward from a central point along the spine of the aircraft.

The U.S. Air Force flew 59 F-117As in total secrecy from the Tonopah Test Range, a secret aircraft testing ground deep in the Nevada desert. These 59 jets were America’s ace in the hole, 59 jets capable of infiltrating enemy airspace and striking targets on the ground with great precision. There was nothing like them anywhere else in the world.

The F-117A fleet was revealed to the world in 1988, the same year the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber was unveiled. The B-2’s bat-winged, boomerang shape dispensed with vertical stabilizers altogether, resulting in an even smaller radar cross-section. Later stealth jets, including the F-22 Raptor fighter, F-35 Lightning II strike fighter, and B-21 Raider strategic bomber concentrated on making stealth more affordable and easier to maintain.

The Toolbox of Air Warfare

Once it became clear that stealth was viable in attack aircraft, making stealthy fighters was the obvious next step. Stealthy fighters like the F-22 can remain hidden from detection at higher altitudes and ambush other aircraft. Today, a stealthy aircraft design is recognized as a key part of what makes an aircraft a fifth-generation fighter jet, and notional sixth-generation designs from the United States, Japan, the U.K., and other countries make clear that stealth is here to stay.

Still, stealth is not a miracle solution to the problem of penetrating enemy air defenses or sweeping the enemy’s fighters and bombers from the skies. Like everything else in the world of warfare, stealth is locked in a perpetual arms race of measure and countermeasure, and there is a real possibility that technological advances, like quantum radar, could someday render it obsolete. It’s important to view stealth as just one tool in the toolbox available to modern aircraft that includes things such as multi-purpose radars, electronic warfare, scramjet-powered weapons, AI, offensive/defensive lasers, and more.

The Takeaway

Stealth was the great disruptor in the realm of postwar air warfare, shifting the balance of power from the defender back toward the attacker. Its technological complexity and staggering cost, however, make it available to a select few. Someday, some new tech will disrupt stealth itself, reducing its effectiveness or making it completely obsolete. What air forces today view as necessary may be worthless tomorrow.

Kyle Mizokami

Kyle Mizokami

Kyle Mizokami is a writer on defense and security issues and has been at Popular Mechanics since 2015. If it involves explosions or projectiles, he’s generally in favor of it. Kyle’s articles have appeared at The Daily Beast, U.S. Naval Institute News, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, Combat Aircraft Monthly, VICE News, and others. He lives in San Francisco.