“I kept finding things that I thought were curious,” she says.

Street’s work had taken her into the heart of a special collection of fossilized marine animals, a trove of 75-million-year-old treasures that tells a story of burgeoning life and sudden death.

The collection of about 3,100 fossils had been found tightly packed into an area of about five or six square meters in Herschel, Saskatchewan.

Map by Sampson et al./Wikimedia Commons

Herschel is about as far from the ocean as you can get in Canada, but 75 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous, it was underwater. The Western Interior Seaway cut a huge channel through North America, splitting the continent into separate land masses.

Discovering such a dense concentration of marine fossils is rare—and it takes time to understand what the specimens show. Street has now coauthored a paper about the fossils, along with her colleagues Emily Bamforth, also at the T.rex Discovery Centre, and Meagan Gilbert, a geologist at the Saskatchewan Geological Survey.

Though staff from the Royal Saskatchewan Museum have been studiously gathering material from the Herschel site for 30 years, most of the finds had never been formally examined before. In fact, there are still many more fossils at the site waiting to be excavated. “We haven’t found the end of it, it just keeps going back into the hill,” says Bamforth.

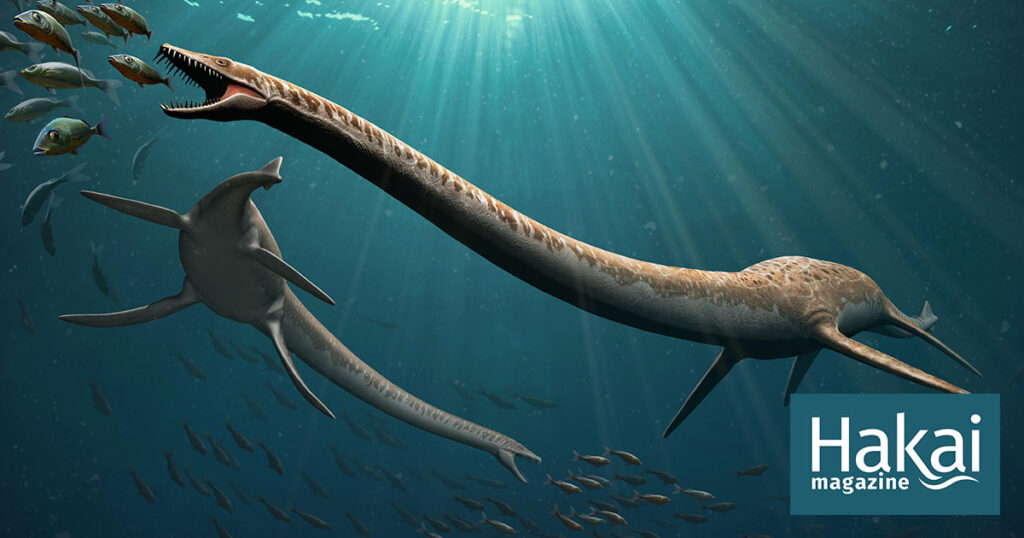

Most of the remains are of majestic marine reptiles called plesiosaurs.

“Usually, the Loch Ness monster is modeled after a plesiosaur,” explains Street. Plesiosaurs had paddle-like limbs and long necks, and stretched eight to 10 meters long. The Western Interior Seaway was teeming with them. The Herschel site also holds remains of mosasaurs, which were a similar size but more fearsome-looking. A bit like a giant Komodo dragon with paddle-like limbs, they were top predators in the area.

The sheer number of plesiosaur fossils at the excavation site is striking. Street’s work in the archive revealed the site was awash with juveniles as well as adults. “I think the plesiosaurs were using it as a nursery,” says Street.

Why such a dense clump of bones on the seafloor? The researchers think they were deposited during a time of low sediment input from nearby rivers, perhaps because a nearby marsh soaked up that sediment before it got to the shallows. This happened in a basin-like area just off the coast, says Street—one probably sheltered by barrier islands.

There was another conundrum, however. Some of the bones showed unusual patterns of decay, almost like they had been rapidly eroded. The researchers think that when the plesiosaurs died, their bodies fell to the seafloor and were scavenged by other creatures. The decayed bones, the researchers surmise, were actually plesiosaur remains that had been partially eaten.

The scene was akin to a modern-day whale fall, when the carcass of a whale ends up on the ocean floor only to be scavenged by crustaceans, worms, or snails. Similar creatures probably had their fill of sunken plesiosaurs 75 million years ago.

The Herschel excavation in Saskatchewan has unearthed plenty of adult and juvenile plesiosaurs, which Hallie Street suggests is a sign the animals were using the site as a nursery. Photo by Hallie Street

The layer of fossils above the plesiosaurs in the Herschel bone bed tells a very different story. Thinner and full of fossilized fish, this layer suggests a moment when something changed dramatically. Fish and sharks were seemingly quickly killed off in large numbers. The air-breathing reptiles didn’t seem to have been affected, but animals that extracted oxygen from the water using gills clearly were. The team’s best guess? The sea turned toxic.

Street thinks it may have started with the plesiosaurs or, more specifically, the creatures and bacteria that devoured their carcasses. They may have caused an unfortunate chain reaction by using up the oxygen in the water and pumping the seabed full of sulfuric compounds. These changes are a natural consequence of decomposition, but taken to extreme levels are known as euxinia.

At the same time, ongoing sea level rise may have brought denser water into the area, trapping the euxinic water deep in the water column. Unable to mix and disperse, the now-toxic water would have turned the once-thriving basin into a grisly, invisible death zone.

The ongoing investigations of the Herschel site reveal a world different from our own, but where processes similar to ones we still see today were taking place, says Jordan Mallon, a paleobiologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature.

“It sort of drives home the point that the players can change through time, and yet the roles effectively remain the same. Where we might talk about whale falls today, 75 million years ago you might have talked about plesiosaur falls.”

And there may be a lesson here too, Bamforth suggests. Today, there are coastal basins where similar accumulations of corpses may be occurring and where euxinia could strike in the right conditions. We’re already seeing some of those conditions begin to develop, including lower oxygen levels in the ocean thanks to warming.