Soldiers hoist a field gun up a cliff face. 1917.

In May 1915, Italy attacked Austria-Hungary along the Isonzo River and in the Trentino, hoping to conquer territory which it believed to be rightfully Italian. Unlike the larger-scale battles, this battle was dictated by the landscape of the sizable mountain range.

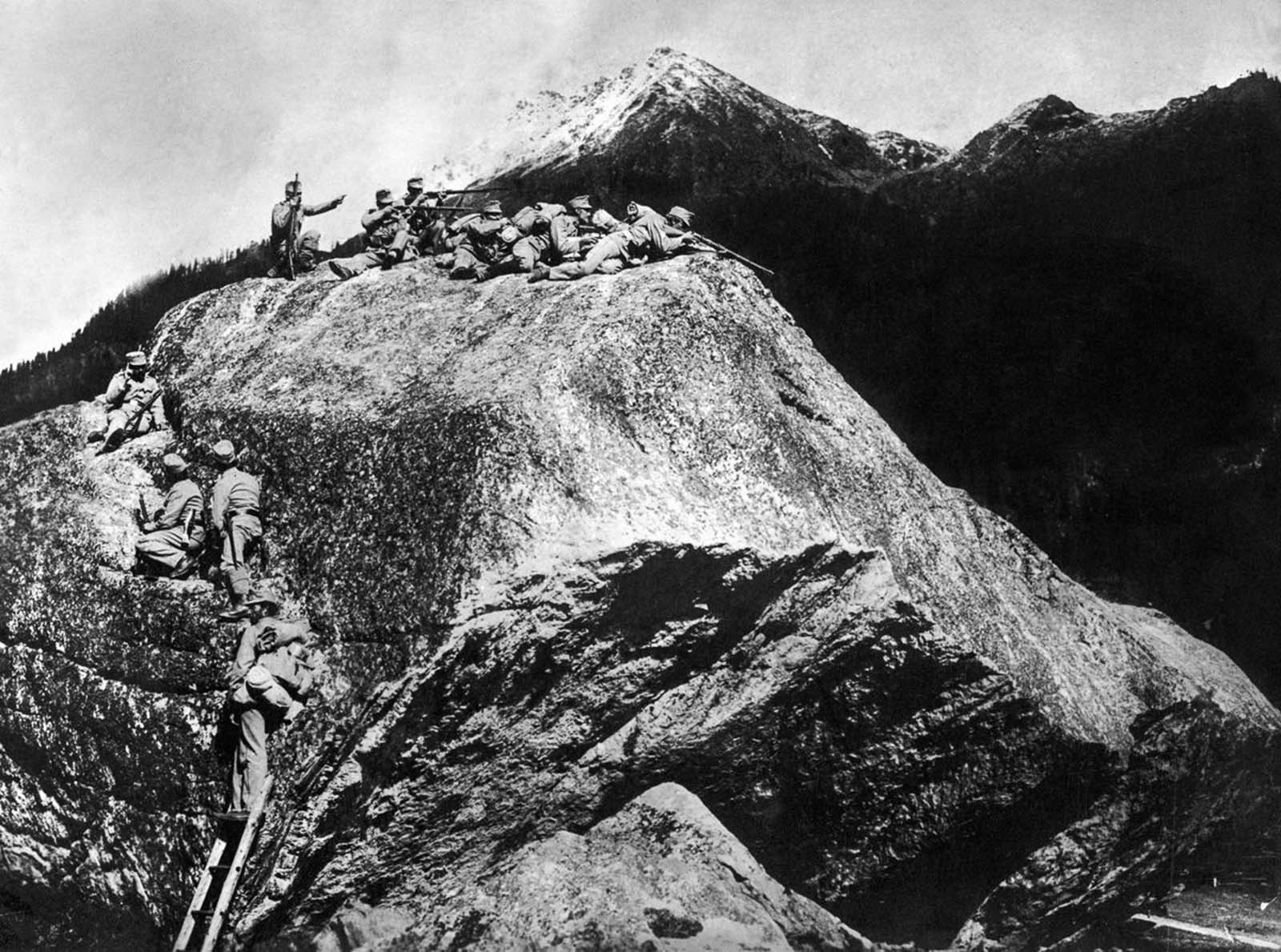

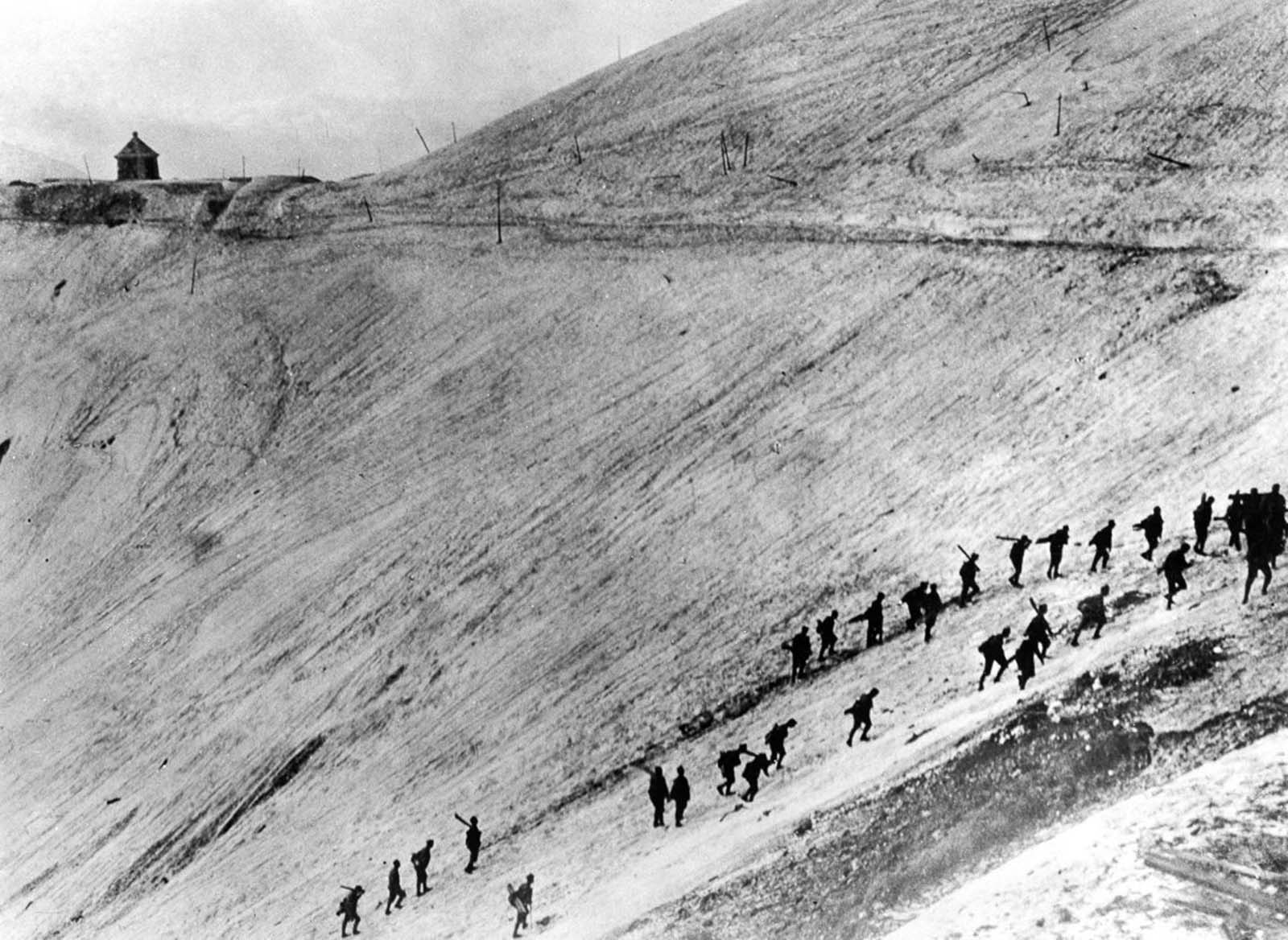

Because of the challenging terrain, both countries had to rely on innovative methods of warfare and outstanding acts of bravery. The Alpine landscape was incredibly challenging: mountain peaks in the combat zone were up to 2000m above sea level, with some slopes of up to 80° steepness.

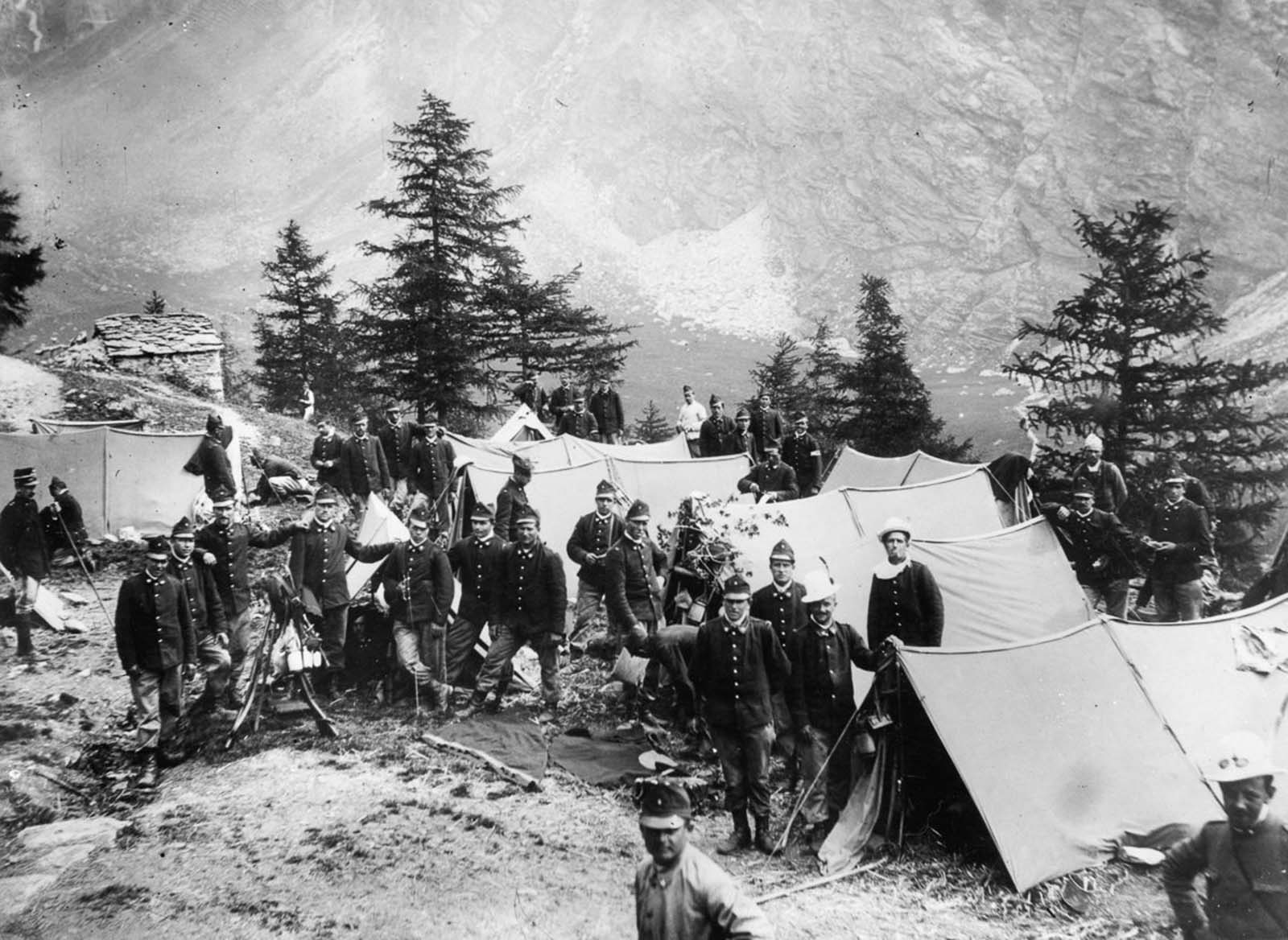

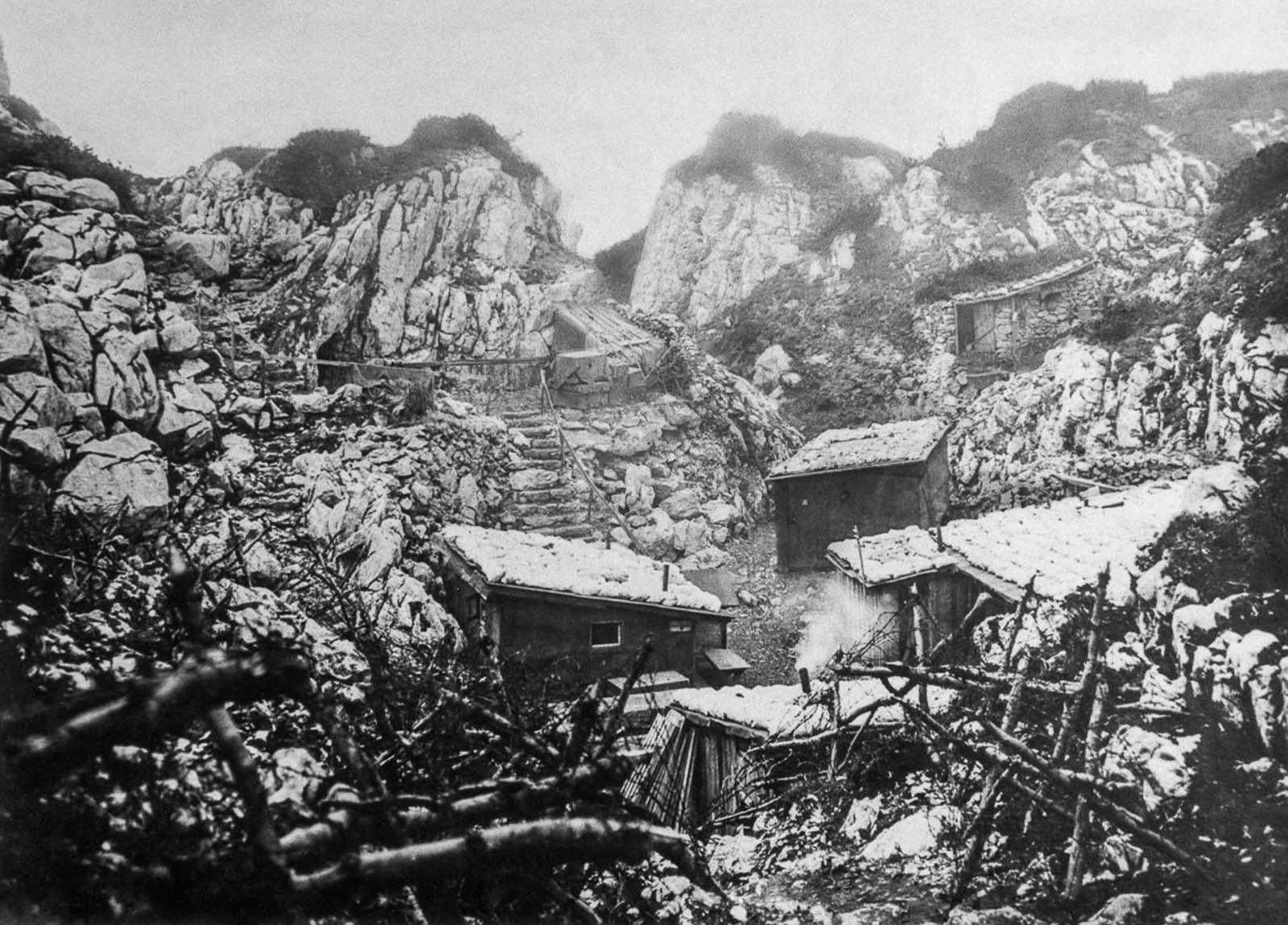

Fast-flowing rivers ran through glacial troughs and there were minimal road and rail connections to the area. In order to make the landscape more suitable for warfare, intensive road-building programmes took place; both armies also had to build bridges across mountain ravines, and to construct forts, barracks, and huts to serve as accommodation, as well as digging trenches (where possible) or using high explosive to create networks of underground caves and tunnels for protection, accommodation, and storage.

The Italians used cable cars and mules to transport food and munitions up to the mountain-top front lines – and to take the wounded back down to the plains, where hospitals were situated.

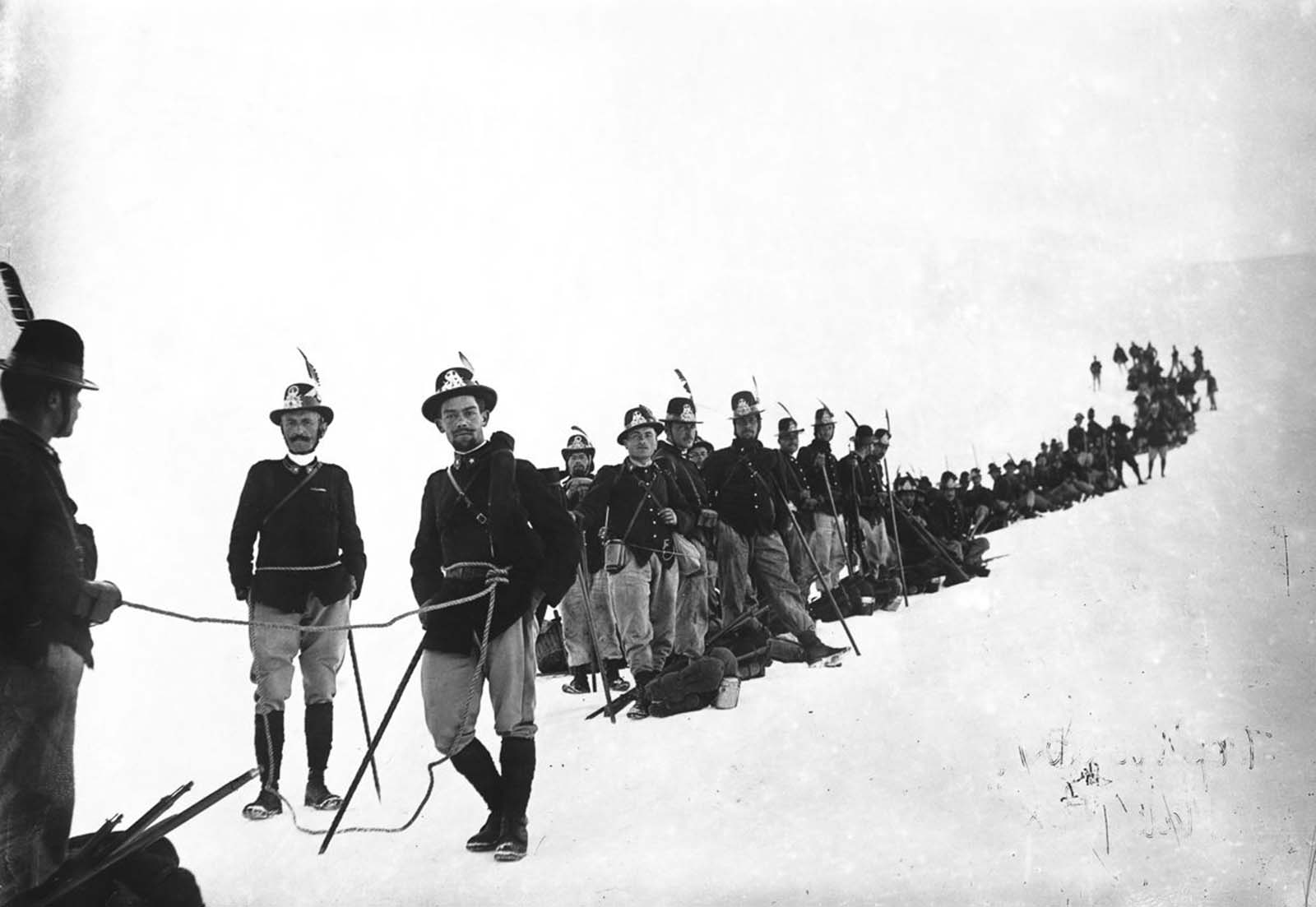

Temperatures remained below freezing for at least four months of each year and snow was a constant presence in winter, with improvised ‘snow trenches’ being used for defense.

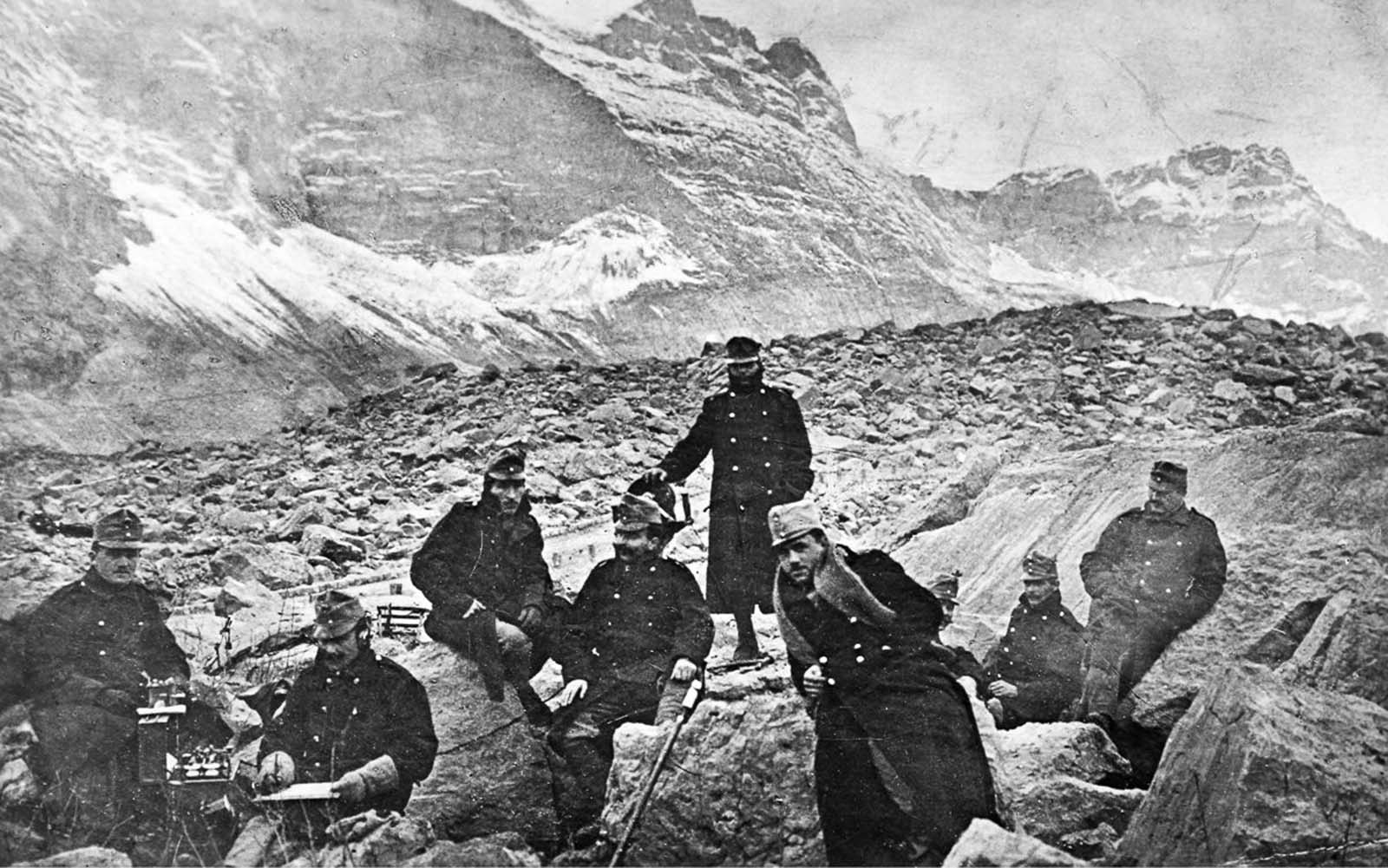

Italian generals in the Carnic Alps. 1915.

Both armies trained specialist ski units as well as equipping soldiers with ice-picks, ropes, snowsuits, cold-weather clothing, and goggles for use on glaciers. Cold and frostbite were real problems for all men in the high Alps, especially when it came to treating the wounded, who suffered terribly from the extreme conditions.

Unsurprisingly, combat was very difficult under these circumstances. Artillery could not accurately identify enemy targets due to the uneven terrain, and without effective artillery fire it was extremely difficult to launch a successful attack.

Meanwhile, infantrymen carrying heavy packs and weapons struggled to attack up steep slopes, since defending troops held the high ground wherever possible, placing the assailants in the face of enemy fire.

Units quickly became separated as they scrambled over rough terrain, while the impact of shells exploding on the rocky surface often led to landslides and falling stones, which had devastating effects.

Both the Italian and the Austro-Hungarian armies had dedicated mountain troops, the Alpini and the Gebirgstruppe respectively; these expert units had special training and equipment to prepare them for service in the mountains. They were renowned for their courage and skill, fighting fiercely under the most challenging circumstances.

But there were not enough of these specialists, and it would have been impossible to limit mountain operations to these troops alone. Instead, the vast majority of men in both armies would have served in mountainous terrain at some stage in the war, including many – such as soldiers from southern Italy or Sicily – who had no experience of such extreme temperatures.

Austrian soldiers move out on skis. 1915.

From 1915, the high peaks of the Dolomites range were an area of fierce mountain warfare. In order to protect their soldiers from enemy fire and the hostile alpine environment, both Austro-Hungarian and Italian military engineers constructed fighting tunnels which offered a degree of cover and allowed better logistics support.

Working at high altitudes in the hard carbonate rock of the Dolomites, often in exposed areas near mountain peaks and even in glacial ice, required extreme skill of both Austro-Hungarian and Italian miners.

Beginning on the 13th, later referred to as White Friday, December 1916 would see 10,000 soldiers on both sides killed by avalanches in the Dolomites. Numerous avalanches were caused by the Italians and Austro-Hungarians purposefully firing artillery shells on the mountainside, while others were naturally caused.

In addition to building underground shelters and covered supply routes for their soldiers like the Italian Strada delle 52 Gallerie, both sides also attempted to break the stalemate of trench warfare by tunneling under no man’s land and placing explosive charges beneath the enemy’s positions. Between 1 January 1916 and 13 March 1918, Austro-Hungarian and Italian units fired a total of 34 mines in this theatre of the war.

In October 1917, some 400,000 German and Austro-Hungarian troops attacked the Italian army at Caporetto, 60 miles north of Trieste. Despite outnumbering their attackers by more than two to one, the Italian lines were penetrated almost immediately. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians moved rapidly, outflanking and encircling much of the Italian army.

An Italian alpine regiment on a glacier in the Italian Alps. 1916.

When the battle had run its course by mid-November, 11,000 Italians were dead and more than a quarter-million had been taken as prisoners. A great number of these surrendered voluntarily.

Caporetto was an unmitigated disaster, one of the worst defeats in any theatre of World War I. The Italian government again collapsed and the prime minister and several military commanders were replaced.

With the enemy now threatening Italian territory, Rome adopted more defensive military strategies. They managed to repel another much smaller Austro-Hungarian offensive in mid-1918, then counter-attacked again as the Dual Monarchy crumbled in October 1918.

Italy’s involvement in World War I was disastrous by any measure. More than 650,000 Italian soldiers were killed while more than one million were seriously wounded. More than a half-million civilians died, most as a consequence of food shortages and poor harvests in 1918.

Austrian soldiers defend a mountain outpost in the Isonzo region.

Austrian forces watch the front line from a high point. 1917.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers wear new steel helmets.

Austrian soldiers construct a tunnel near the front. 1918.

An Italian soldier outside a mountain bunker. 1916.

A group of Alpine Infantry soldiers camped at the foot of Mount Vilau. 1915.

Italian artillery gunners load shells decorated with Easter messages. 1916.

A Hungarian Workers Unit transports oven components for use in soldier shelters in the Dolomites. 1916.

Austro-Hungarian heavy artillery in the Karst Mountains.

Austrian mountain infantry haul ordnance up a slope. 1916.

A mule carries heavy weaponry on the high trails of the Isonzo front. 1916.

Austro-Hungarian troop shelters. 1916.

Soldiers haul 7cm guns up a 3,400-meter peak. 1916.

Italian soldiers scale Monte Nero on the Karst plateau during the Second Battle of the Isonzo. 1915.

A soldier carries a field gun to higher ground. 1916.

Italian troops on skis advance on Austrian forces in the Julian Alps. 1916.

A ski patrol in combat on Monte Cevedale. 1917.

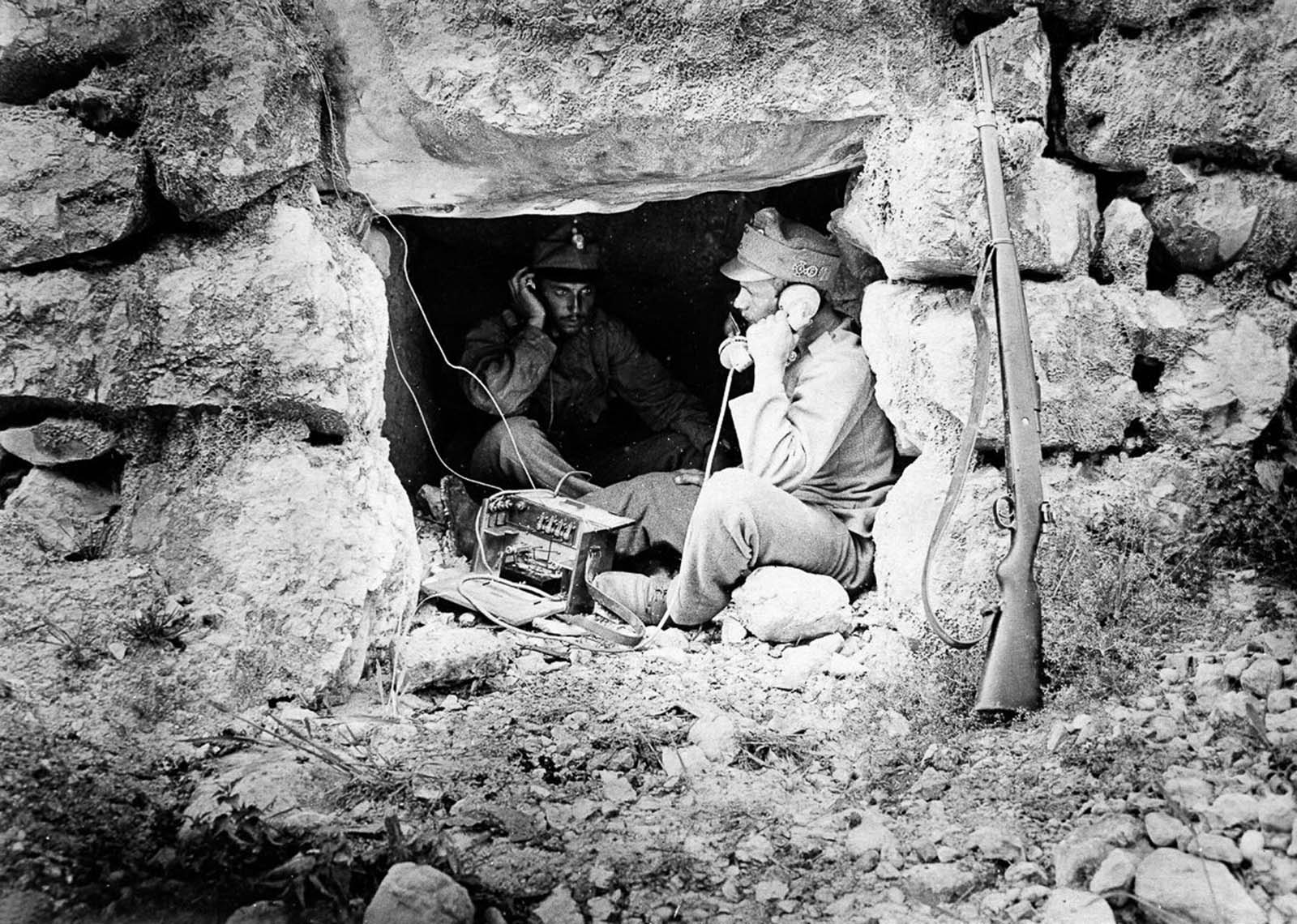

An Austro-Hungarian field telephone outpost on Mount Rombon. 1917.

Soldiers advance to support a flamethrower attack. 1917.

Austrian troops near the front line in the Dolomites. 1917.

Austrian soldiers descend a cliff. 1915.

German soldiers pass through destroyed Italian positions near St. Daniel during the 12th Battle of the Isonzo. 1917.

Members of an Italian alpine regiment leave a stone hut high in the Alps. 1915.

Italian Alpini Companies ski in the Carnic Alps. 1918.

German alpine soldiers. 1915.

Austro-Hungarian troops scale the slopes of Monte Nero. 1917.

Italian Alpini troops. 1915.

Soldiers lower a wounded comrade down a cliff. 1915.

A Swiss soldier mans an army outpost in the high Alps where the war fighting between the Austrians and the Italians can be observed. 1918.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers carry a wounded comrade to a field hospital on Monte Nero. 1916.