The bombing of Berlin, aka the Berlin Air Offensive or Battle of Berlin (Air), was a sustained bombing campaign on the German capital by the British Royal Air Force and United States Air Force from November 1943 until March 1944. The objective, which failed, was to bomb Germany into surrender and win WWII without the necessity of land operations.

Bombed Berlin Reichstag, 1945 Imperial War Museums (Public Domain)

Area Bombing

The commander-in-chief of the RAF Bomber Command, Arthur Harris (1892-1984), had received backing at the highest level for the night-time area bombing (aka carpet bombing) of German industrial targets and industrial cities. The Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Army Air Force (USAAF) had already conducted a Combined Bomber Offensive and made repeated attacks on the Ruhr industrial area of Germany (Battle of the Ruhr, March-July 1943) and on Hamburg with the utterly devastating Operation Gomorrah (July-August 1943). Typically, the RAF bombed by night and the USAAF by day in these combined operations. As Winston Churchill (l. 1874-1965), the British prime minister put it:

We shall bomb Germany by day as well as by night in ever-increasing measure, casting upon them month by month a heavier discharge of bombs, and making the German people taste and gulp each month a sharper dose of the miseries they have showered upon mankind.

By the summer of 1943, the Allied leaders began to shift their focus to a future invasion of Continental Europe. The Allies issued the Pointblank Directive in June 1943, which stated that bombing raids in Europe should prioritise Germany’s capacity to produce fighter planes, which could be used against ground troops in the D-Day Normandy landings (Operation Overlord) planned for the following summer. Air supremacy had to be achieved before Overlord could get underway. However, Harris remained sceptical of the possibility of hitting small but strategically important targets like weapons factories. This was in some way born out by the USAAF’s Schweinfurt-Regensburg raids. The first Schweinfurt raid in August 1943 had not been very successful in damaging the crucial ball-bearing factories, and many aircraft had been lost in the process. (The USAAF returned to Schweinfurt and was more successful in October). Berlin did have key armaments factories, and these could be knocked out with a wider and more indiscriminate bomb-dropping strategy, Harris thought. Berlin was also an obvious transport hub and, of course, a prestige target, too. Harris believed that the heavy bombing of Berlin could ultimately lead to Germany’s surrender and so the Allies might even avoid the necessity of dangerous and time-consuming land operations.

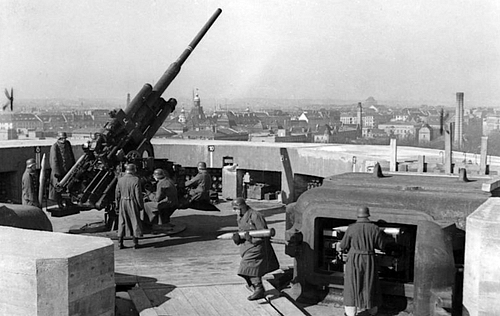

Berlin Anti-aircraft Defences Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27779 (CC BY-SA)

There were some flaws in the plan. Berlin was a much bigger city than those bombed previously and so would take many more raids to damage. Harris knew this, and so he called for a force of 6,000 bombers, but this was never possible; the RAF and USAAF combined only had some 3,000 bomber planes at any one time. Berlin was also well-defended with over 100 anti-aircraft batteries. The historian M. Hastings describes Berlin as “the largest and most heavily defended industrial urban area in Europe” (285). As the historian R. Neillands put it, Berlin “was always a difficult target. It lay a long way into Germany, close to the eastern frontier, and was a very big and very flat city, with few physical features…” (217).

The RAF bomber crews would be on their own in their effort to bomb into submission the city they called “Big B”.

Another problem was that in 1943, Allied fighter planes still did not have sufficient fuel range to escort bombers to targets deep in Germany. Finally, the other bombing campaigns, which included the thousand-bomber raid on Cologne in 1942, had not shattered civilian morale despite causing enormous casualties and damage. This had also been true of the German bombing of British cities and the London Blitz earlier in the war. Even if German civilian morale could be broken, in a totalitarian state built on violence, there was probably not much civilians could do to influence policy change anyway. Despite these pitfalls, the Combined Chiefs of Staff gave Harris the green light, and the bombers were sent to Berlin. Crucially, the USAAF, preferring to pursue its own targets like Germany’s oil supplies, would not join the raids until near the end of the campaign. The RAF bomber crews would be on their own in their effort to bomb into submission the city they called “Big B”.

The Bombers

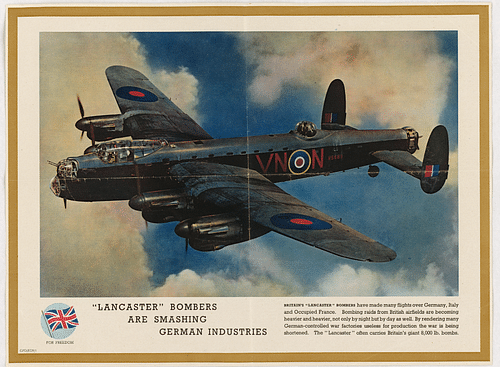

The RAF’s best heavy bomber was the four-engine Lancaster bomber, capable of carrying a bomb load of up to 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg). The RAF also deployed Stirling and Halifax bombers. De Havilland Mosquito bombers, each capable of carrying 4,000 lbs of bombs, were often used for diversionary raids to distract enemy fighters from the larger bomber force of Lancasters. The USAAF deployed such bombers as the B-17 Flying Fortress, capable of carrying a 6,000-lb (2,722 kg) bomb load, and the B-24 Liberator bomber.

Lancaster Bomber Propaganda Poster Office of War Information. (Public Domain)

The first series of attacks on Berlin came in the last week of August and the first week of September 1943, but this was something of a false start. 1,647 bombers were involved, but 126 were lost to enemy fighters like the Messerschmitt Bf 109, the anti-aircraft guns that defended Berlin and on the route to get there, and to general mishaps. A loss rate of 7.7% was deemed too high to be sustained. It was decided to halt the operation until the nights were longer, darkness being the best protection the slow-flying bombers had. Bombing of the German capital was resumed on 18 November. Helped by a diversionary raid elsewhere, of 444 bombers sent to Berlin, just nine were lost. Another three raids were conducted through November. Another four attacks were made in December as Harris pressed on with his objective of flattening the city into submission. The loss rate of planes continued to hover around 5%, but persistently cloudy weather meant bombing was often blind, and reconnaissance planes were frequently unable to record just what damage was being done.

Bad weather could play havoc even at home – 25 Lancasters were lost just after taking off and hitting fog in the early hours of 17 December. Accidents over the target took their toll, too, as the logistics of amassing and then moving a large number of aircraft in a single group was fraught with risk, as here explained by John Cochrane, a bomber gunner:

I think perhaps my most vivid recollection is the first time that my Group went to Berlin. After we had dropped our bombs there’s a manoeuvre as you turn away, one Group has to cross above the other, and the Group on top dropped their bombs right smack on to our squadron. We lost one aeroplane and that was a terrifying memory and an incident that I’ll never forget.

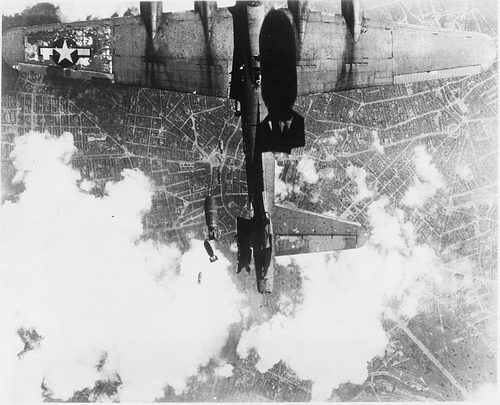

USAAF Bombing Berlin, 1944 National Archives and Records Administration (Public Domain)

By the spring, the time was up for Bomber Command as the Allied leaders looked to gather their resources ready for D-Day.

Into January 1944, the raids kept on coming – five more that month – but Harris was coming under increasing pressure to divert Bomber Command’s formidable resources against more definite air industry targets in Germany. In addition, the weather continued to be unhelpful, stopping operations for two weeks; and the loss rate had crept up to 7%. The next raid, on 15 February, proved costly. 42 bombers were lost from a force of 891. Another raid on 24 March was even worse, with the RAF losing 9% of the aircraft involved: 72 bombers.

These losses were too high to sustain since Bomber Command only ever had around 900 bombers in service at any one time. A loss rate of over 6% meant an airman had no statistical chance of surviving his 30-mission tour of duty. More than 6% losses were also difficult to replace both in terms of machines and trained men. On top of that, Germany had obviously not surrendered.

The USAAF Eighth Air Force, based in Britain, was also adding to the Berliners’ misery in March with its bombers attacking the city in large numbers, but it had become obvious that the original Allied strategy was not going to work. In 16 major attacks, the RAF had lost 492 bombers in the Berlin Air Offensive. In one raid alone on 6 March, a daylight USAAF force had lost 69 bombers over the city as the anti-aircraft defences became ever stronger. There had also been attacks on other targets in Germany – which included the disastrous Nuremberg raid of March 1944 when the RAF lost around 100 bombers – since if the Allies had concentrated only on Berlin then the Germans would have been free to move all of their defences, including fighter planes, to the capital. By the spring of 1944, the time was up for Bomber Command as the Allied leaders looked to gather their resources ready for D-Day that coming summer. Berlin, albeit terribly battered, had not succumbed. In this sense, the bombing of Berlin was an Allied defeat.

Allied Strategic Bombing of Germany, 1940 – 1945 Simeon Netchev (CC BY-NC-SA)

The Damage

The bombing of Berlin might not have achieved the attacker’s objective but it still caused tremendous damage. The bombers had dropped a mixture of explosive and incendiary bombs. The former were designed to first smash through the roofs and floors of buildings, and the latter were then dropped to fall deep into the debris, setting it aflame.

The German Minister of Armaments Albert Speer (1905-81) describes his view of the bombing from an anti-aircraft gun platform in the heart of the city:

From the flak tower the air raids on Berlin were an unforgettable sight, and I had constantly to remind myself of the cruel reality in order not to be completely entranced by the scene: the illumination of the parachute flares, which the Berliners called “Christmas Trees” [RAF target markers], followed by flashes of explosions which were caught by the clouds of smoke, the innumerable probing searchlights, the excitement when a plane was caught and tried to escape the cone light, the brief flaming torch when it was hit. No doubt about it, this apocalypse provided a magnificent spectacle.

As soon as the planes turned back, I drove to those districts of the city where important factories were situated. We drove over streets strewn with rubble, lined by burning houses. Bombed-out families sat or stood in front of the ruins. A few pieces of rescued furniture and other possessions lay about on the sidewalks. There was a sinister atmosphere full of biting smoke, soot, and flames. Sometimes the people displayed that curious hysterical merriment that is often observed in the midst of disasters. Above the city hung a cloud of smoke that probably reached twenty thousand feet in height. Even by day it made the macabre scene as dark as night.

On November 26, 1943, four days after the destruction of my Ministry, another major air raid on Berlin started huge fires in our most important tank factory, Allkett. The Berlin central telephone exchange had been destroyed…Meanwhile I had arrived at Allkett. The greater part of the main workshop had burned down, but the Berlin fire department had already succeeded in extinguishing the fire.

Albert Speer, 1943 Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J14204 (CC BY-SA)

A conservative estimate is that more than 400,000 people lost their homes in the bombing of Berlin. The November raids alone killed 4,000 civilians, but as the campaign wore on, there were fewer proportional casualties as the homeless Berliners left the city in the tens of thousands.

Aftermath

The wider Combined Bombing Offensive did cause Germany to withdraw troops and arms from the Eastern Front to protect its own cities. In 1941, Germany engaged 65% of its forces in the east, but in 1944, this figure was reduced to 32% (Dear, 15). Anti-aircraft guns and personnel, in particular, were diverted in massive numbers and many went to defend Berlin. There was also severe disruption to the armaments industry and to the transportation of materials and soldiers. As Speer noted, the air war was a vital front of the war, and “this was the greatest lost battle on the German side” (Dear, 15).

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin GerardM (CC BY-SA)

Even at the time, the heavy losses in fliers and aircraft, the lack of evidence that German civilian morale was being broken, and the concern over high civilian casualties all contributed to seriously discredit the idea of area bombing both in the minds of the military decision-makers and the general public. Technology helped revive the idea of large-scale bombing raids when new fighters like the P-51 Mustang, able to operate at a much longer range than previous fighters, meant that bombers could be escorted to targets deep in Germany. More German cities, including Berlin, would be bombed again before the war was over, infamous amongst these raids was the bombing of Dresden in 1945 (February-March). Area bombing was also used outside Europe. From May to July 1945, in order to avoid just such a ground offensive as the Normandy landings, the civilians of almost all Japanese cities faced massive bombing raids, a campaign of terror that culminated in the total devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki using atomic bombs.

The fall of Berlin finally came when the city was occupied by a Russian army led by Marshall Georgy Zhukov (1896-1974) at the end of April 1945. On 30 April, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his bunker beneath the city. On 2 May, the city surrendered. It would take many years for Berlin to recover from the bombs and shells. The Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church was damaged in the bombing but left with its tower unrepaired as a permanent memorial to those who lost their lives in the war.