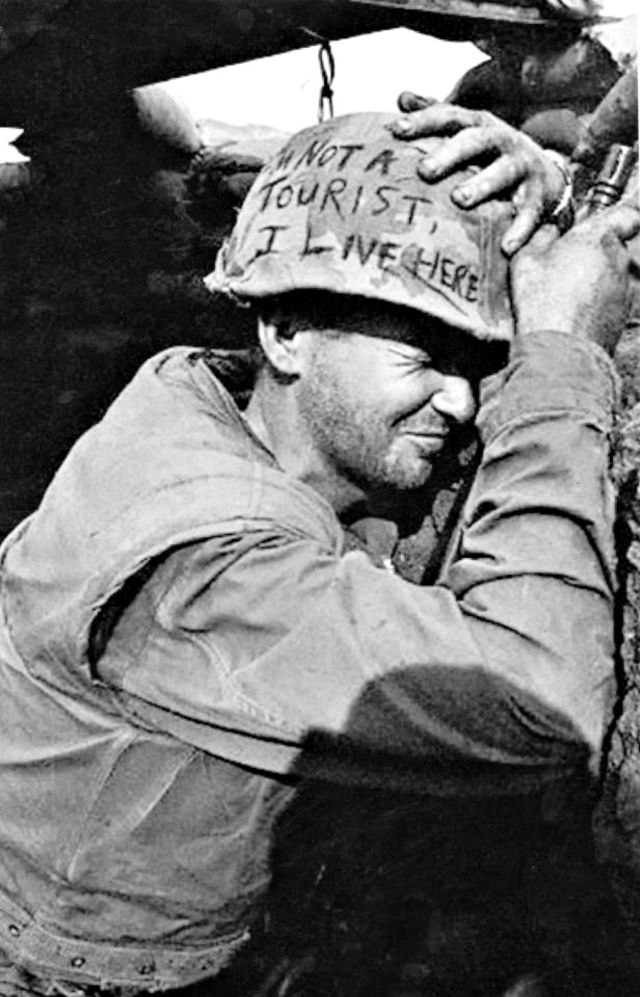

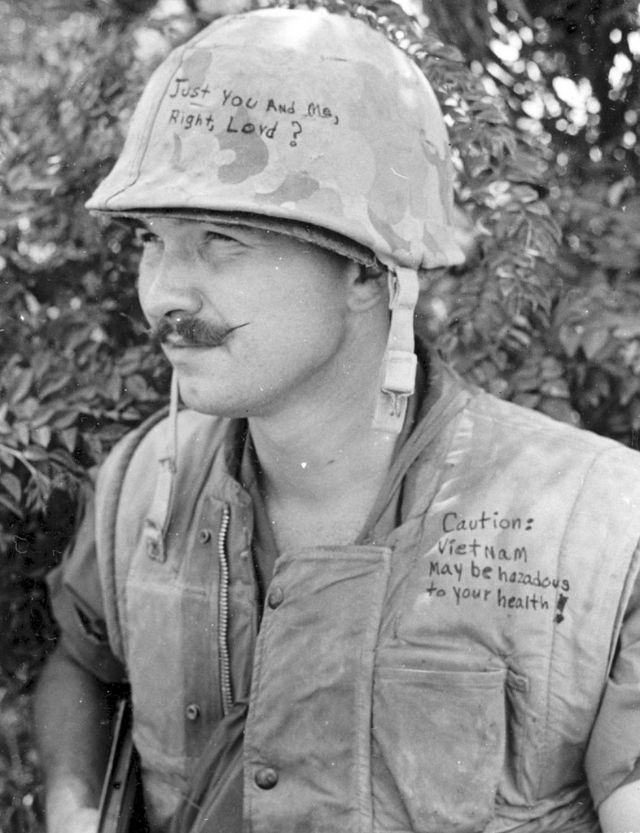

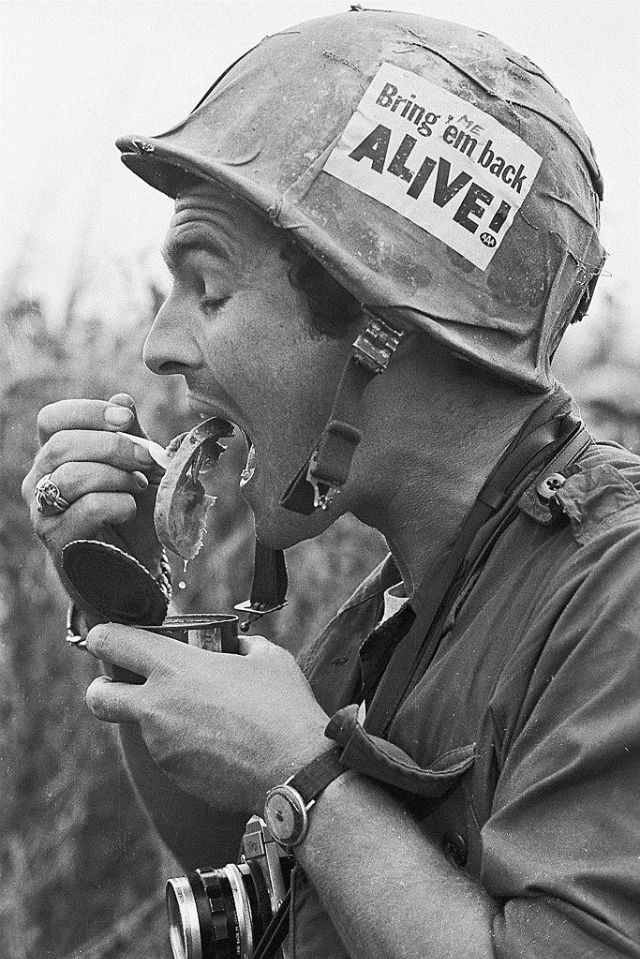

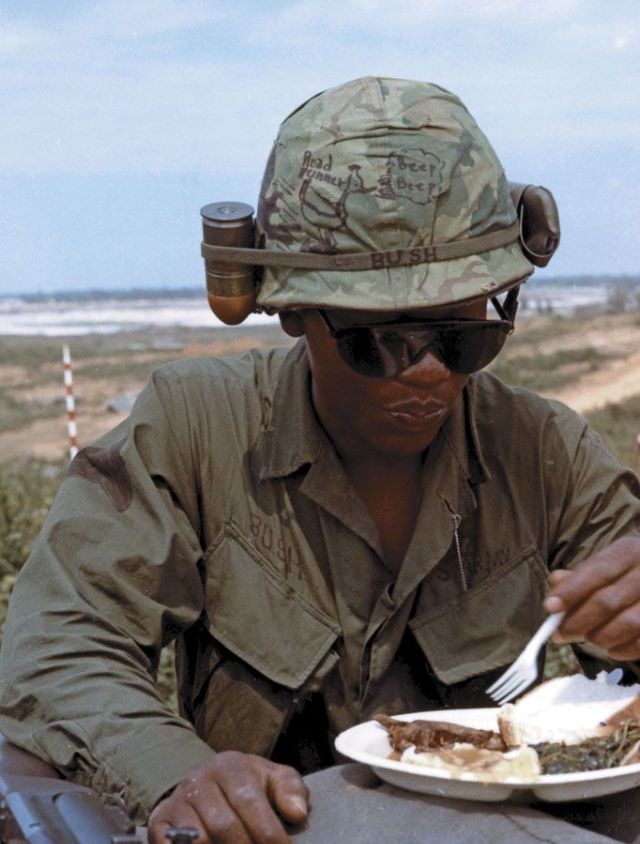

Amid the chaos and violence of the Vietnam War, American soldiers adorned their helmets with intricate and often striking artwork.

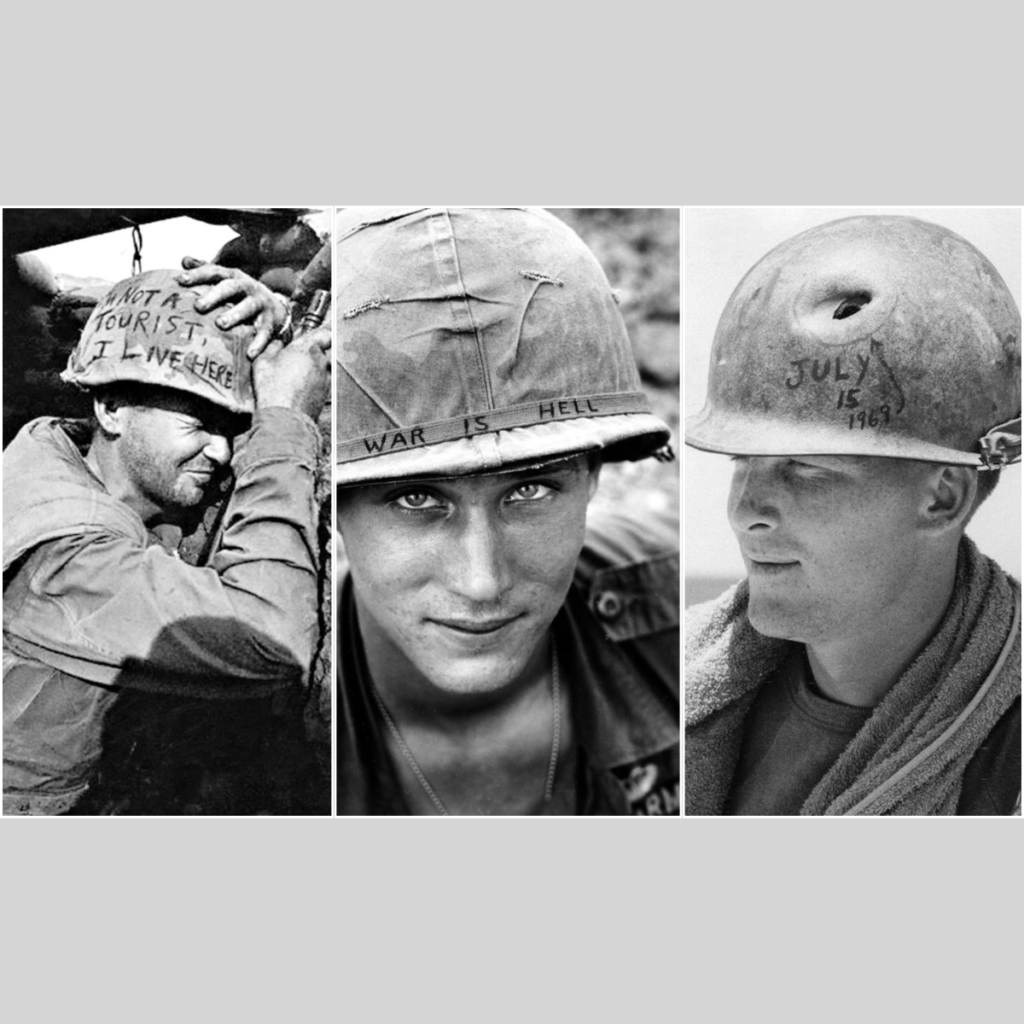

These helmet designs served as a means of personal expression, conveying messages of patriotism, camaraderie, and protest.

Today, these helmets stand as powerful symbols of the human experience of war, offering a glimpse into the minds and hearts of those who lived through it.

In this context, the study of helmet art of the Vietnam War is a fascinating and thought-provoking subject, shedding light on the intersection of art, history, and human psychology.

The practice of decorating military helmets dates back centuries, but it was during the Vietnam War that the tradition truly flourished.

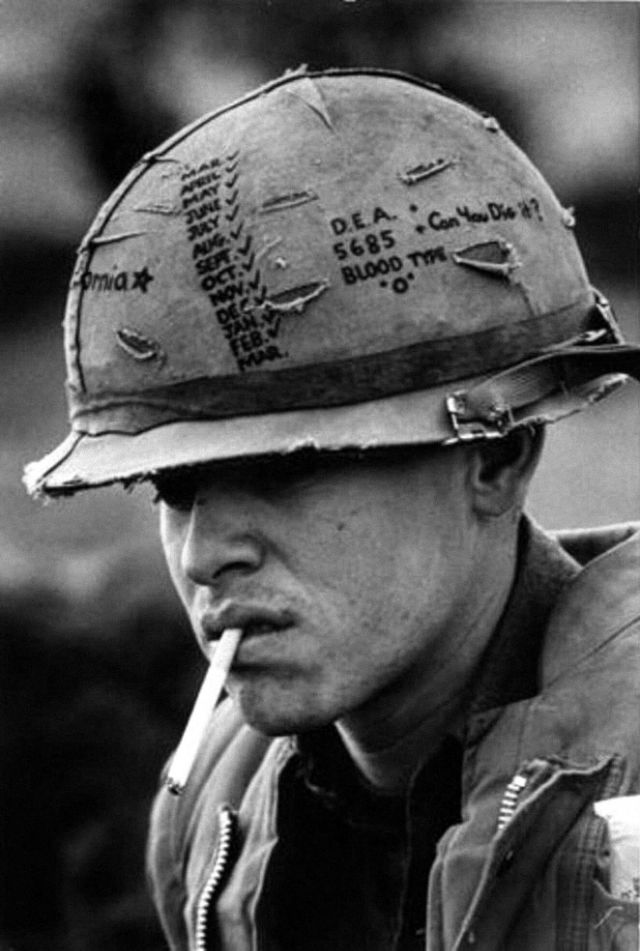

While technically, soldiers were not allowed to decorate their gear, most commanding officers allowed some individuality as long as it did not reflect badly upon the unit or branch.

However, while commanding officers allowed some leniency regarding graffiti, men were still instructed to stay away from photographers and journalists.

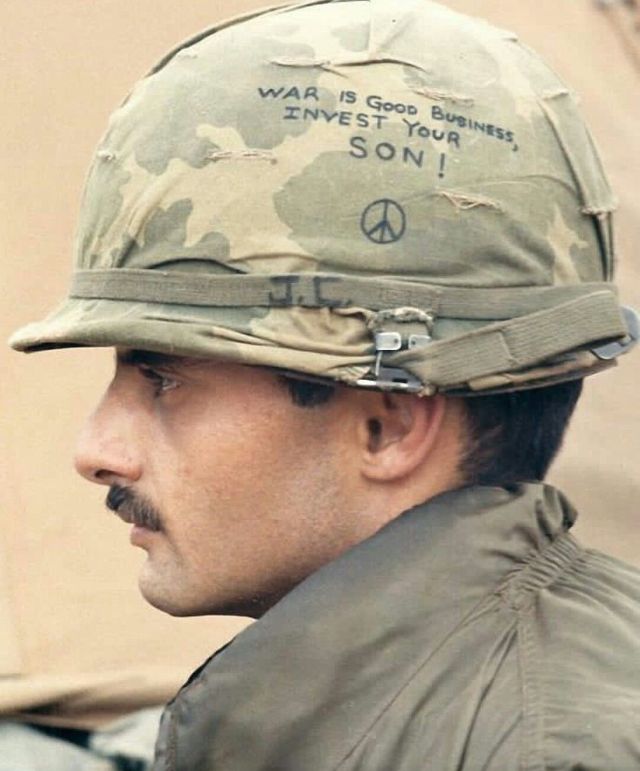

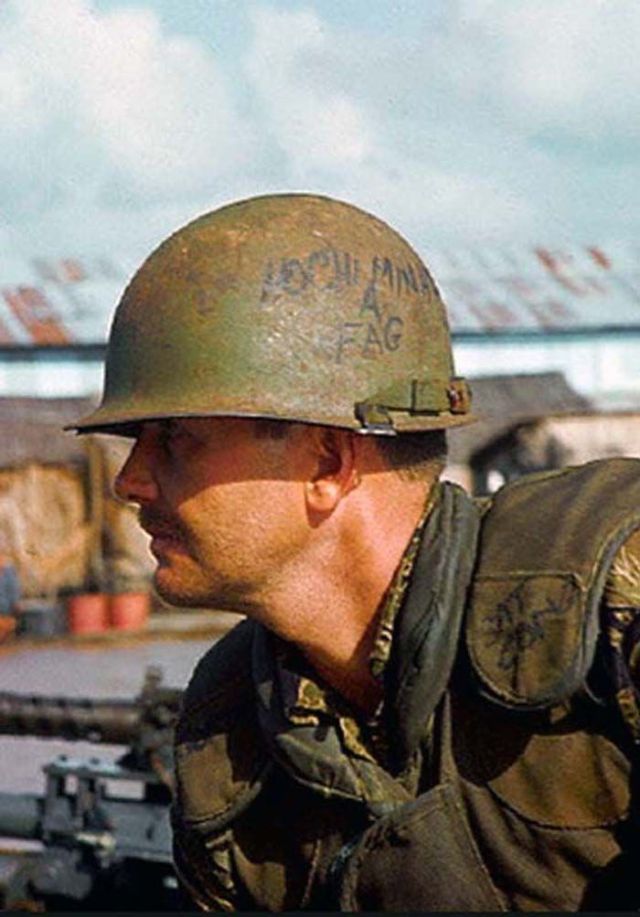

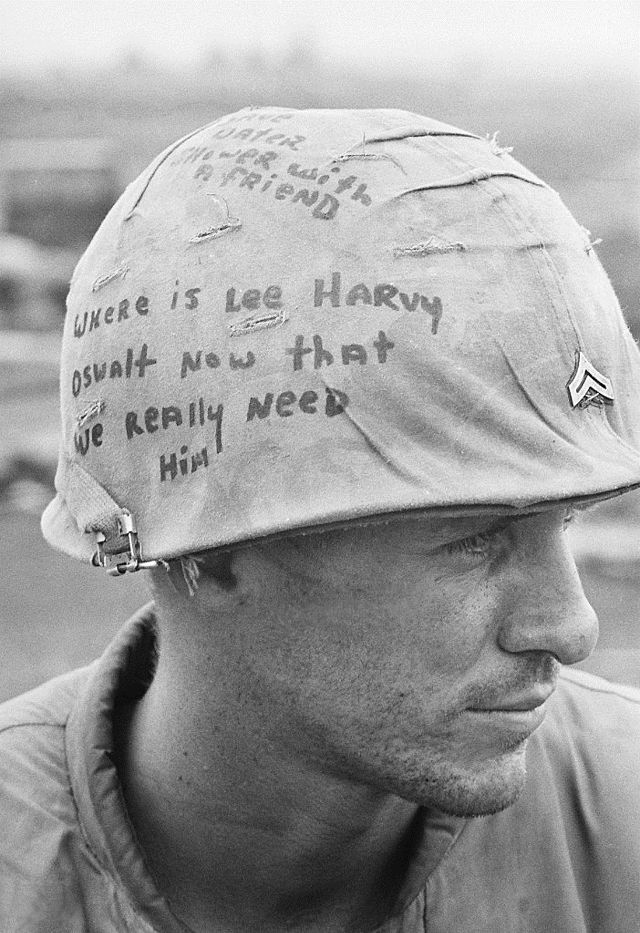

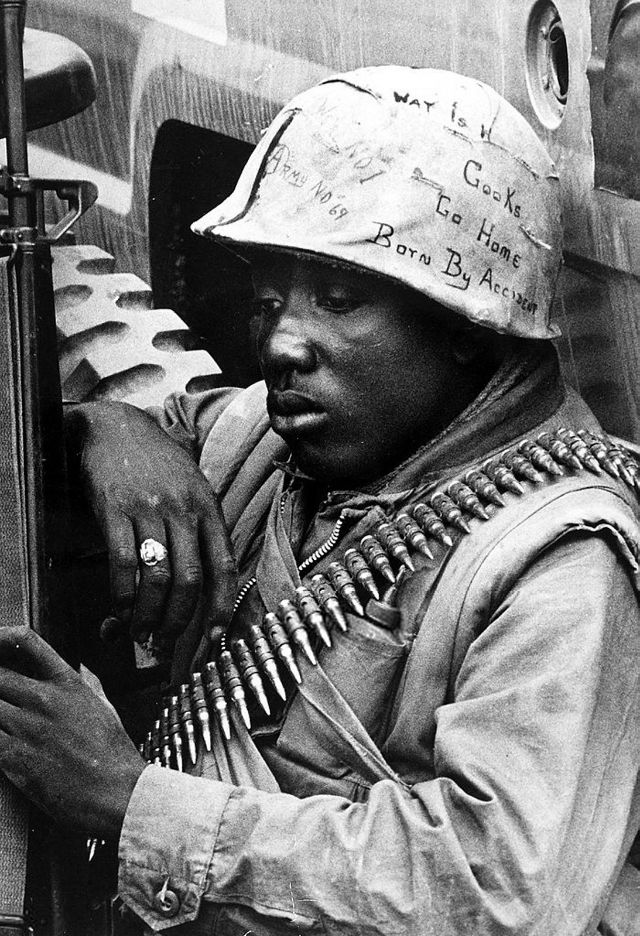

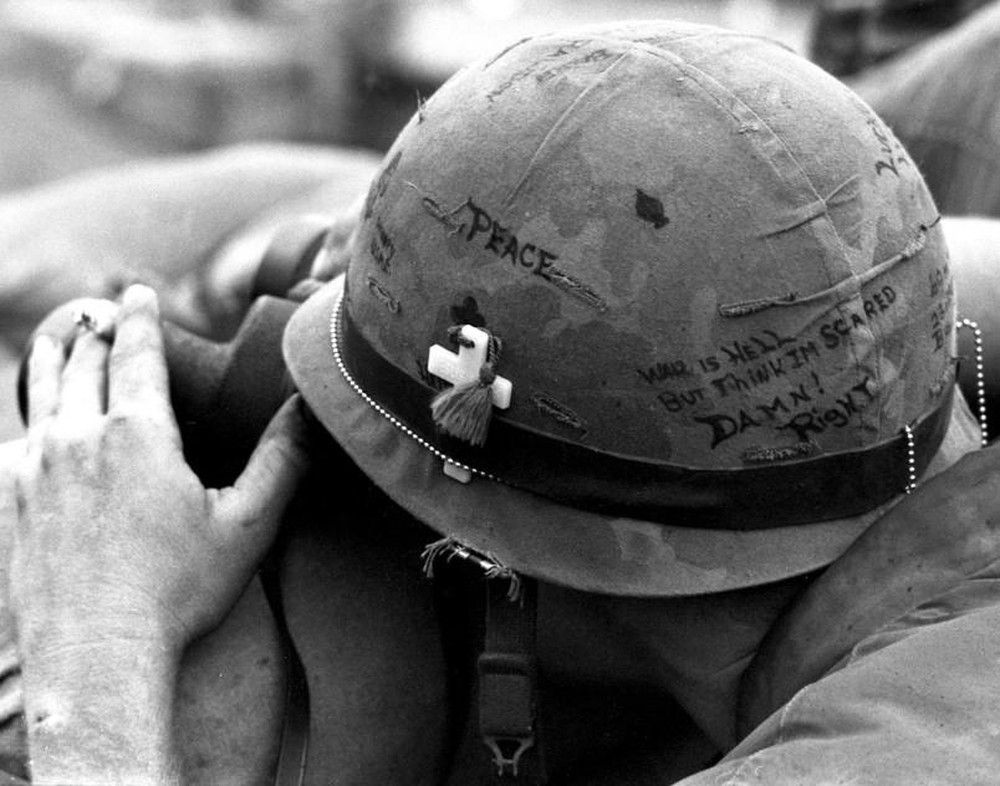

As the War drug on some of the designs began to develop anti-war sentiments, whether consciously or subconsciously.

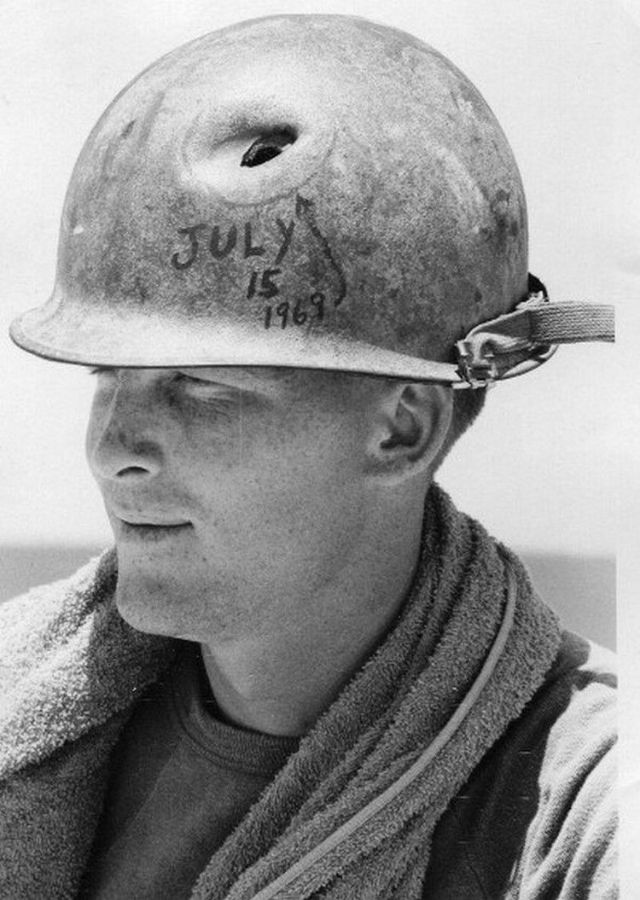

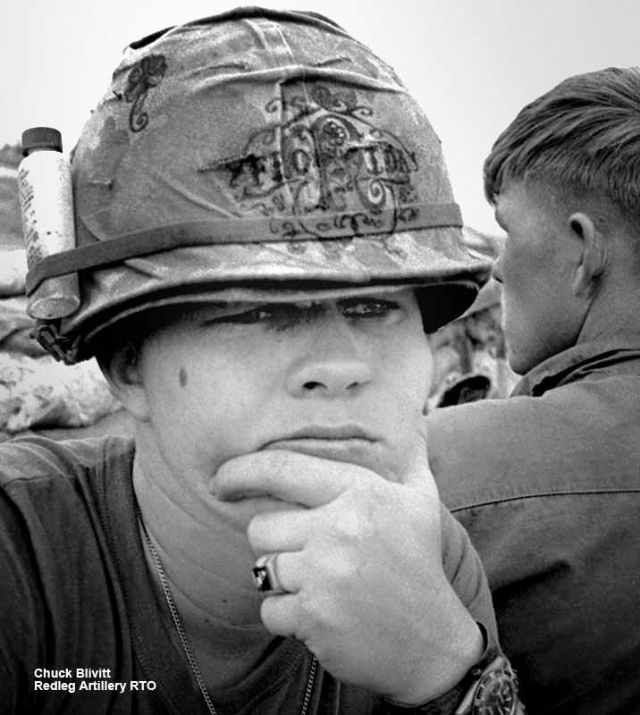

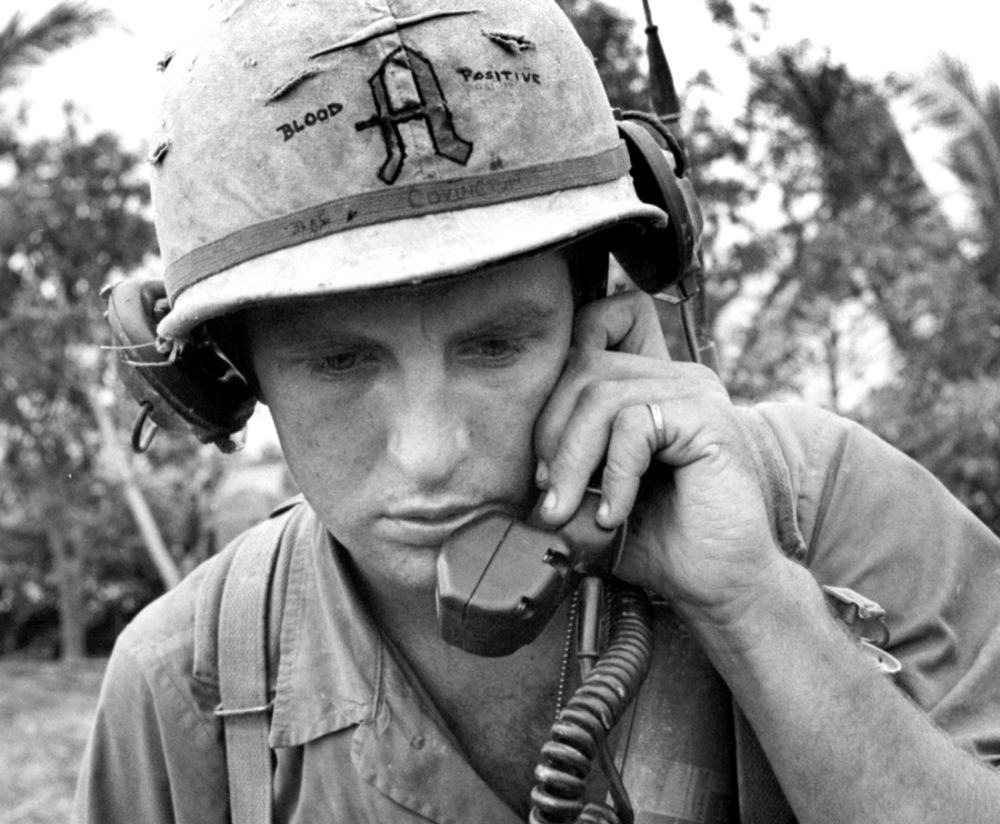

The designs on these helmets varied widely, from simple initials and insignia to elaborate illustrations and slogans. Some soldiers painted scenes of home or loved ones, while others depicted violent or provocative imagery.

The designs on these helmets varied widely, from simple initials and insignia to elaborate illustrations and slogans. Some soldiers painted scenes of home or loved ones, while others depicted violent or provocative imagery.

One of the most famous examples of helmet art from the Vietnam War is the “Death Card” design, popularized by the 1st Cavalry Division.

The design featured a skull with wings and the phrase “When I Die, I’ll Go To Heaven, Because I’ve Spent My Time In Hell.” This design became a symbol of the fierce fighting spirit of the division and was widely adopted by other units.

Other common slogans were “War is Hell,” “Kill a Commie, for Mommy,” “War is Good Business, Invest Your Son” and “Hear All Evil, See All Evil, Kill All Evil.”

Another popular design was the “Peace Symbol,” which featured a simple drawing of a dove or the peace sign. This design was often used by soldiers who opposed the war and sought to express their anti-war sentiments.

Many of these soldiers were conscientious objectors or protesters who had been drafted into military service.

Other designs were more personal in nature, featuring family members, pets, or hometowns. These designs served as a reminder of what soldiers were fighting for and what they hoped to return to when the war was over.

Other designs were more personal in nature, featuring family members, pets, or hometowns. These designs served as a reminder of what soldiers were fighting for and what they hoped to return to when the war was over.

Still, others featured humorous or irreverent slogans, reflecting the soldiers’ need to find levity and humor amid the chaos and horror of war.

While helmet art was an important part of the soldier’s experience during the Vietnam War, it was not without controversy.

Some military officials viewed the practice as a distraction or even a violation of military protocol. In some cases, soldiers were ordered to remove their helmet art or face disciplinary action.

Despite these concerns, helmet art remained a beloved tradition among soldiers throughout the Vietnam War and beyond.

The war exacted an enormous human cost: estimates of the number of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians killed range from 966,000 to 3 million. Some 275,000–310,000 Cambodians, 20,000–62,000 Laotians, and 58,220 U.S. service members also died in the conflict.

The war exacted an enormous human cost: estimates of the number of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians killed range from 966,000 to 3 million. Some 275,000–310,000 Cambodians, 20,000–62,000 Laotians, and 58,220 U.S. service members also died in the conflict.

The end of the Vietnam War would precipitate the Vietnamese boat people and the larger Indochina refugee crisis, which saw millions of refugees leave Indochina, an estimated 250,000 of whom perished at sea.

Once in power, the Khmer Rouge carried out the Cambodian genocide, while conflict between them and the unified Vietnam would eventually escalate into the Cambodian–Vietnamese War, which toppled the Khmer Rouge government in 1979.

In response, China invaded Vietnam, with subsequent border conflicts lasting until 1991. Within the United States, the war gave rise to what was referred to as Vietnam Syndrome, a public aversion to American overseas military involvements, which, together with the Watergate scandal contributed to the crisis of confidence that affected America throughout the 1970s.

In the domestic debate over the reasons for the US being unable to defeat North Vietnamese forces during the war, conservative thinkers, many of whom were in the US military, argued that the US had sufficient resources but that the war effort had been undermined at home. I

In the domestic debate over the reasons for the US being unable to defeat North Vietnamese forces during the war, conservative thinkers, many of whom were in the US military, argued that the US had sufficient resources but that the war effort had been undermined at home. I

n an article in Commentary, “Making the World Safe for Communism,” the journalist Norman Podhoretz stated:

Do we lack power?… Certainly not if power is measured in brute terms of economic, technological, and military capacity. By those standards, we are still the most powerful country in the world…. The issue boils down in the end, then, to the question of will.

The term “Vietnam Syndrome” thereafter proliferated in the press and policy circles as a way of explaining the United States, one of the world’s superpowers, failing to repel North Vietnam’s invasion of South Vietnam.

Many hawkish conservatives such as Ronald Reagan agreed with Podhoretz. In time, the term “Vietnam Syndrome” expanded as a shorthand for the idea that Americans were worried they would never win a war again and that their nation was in utter decline.