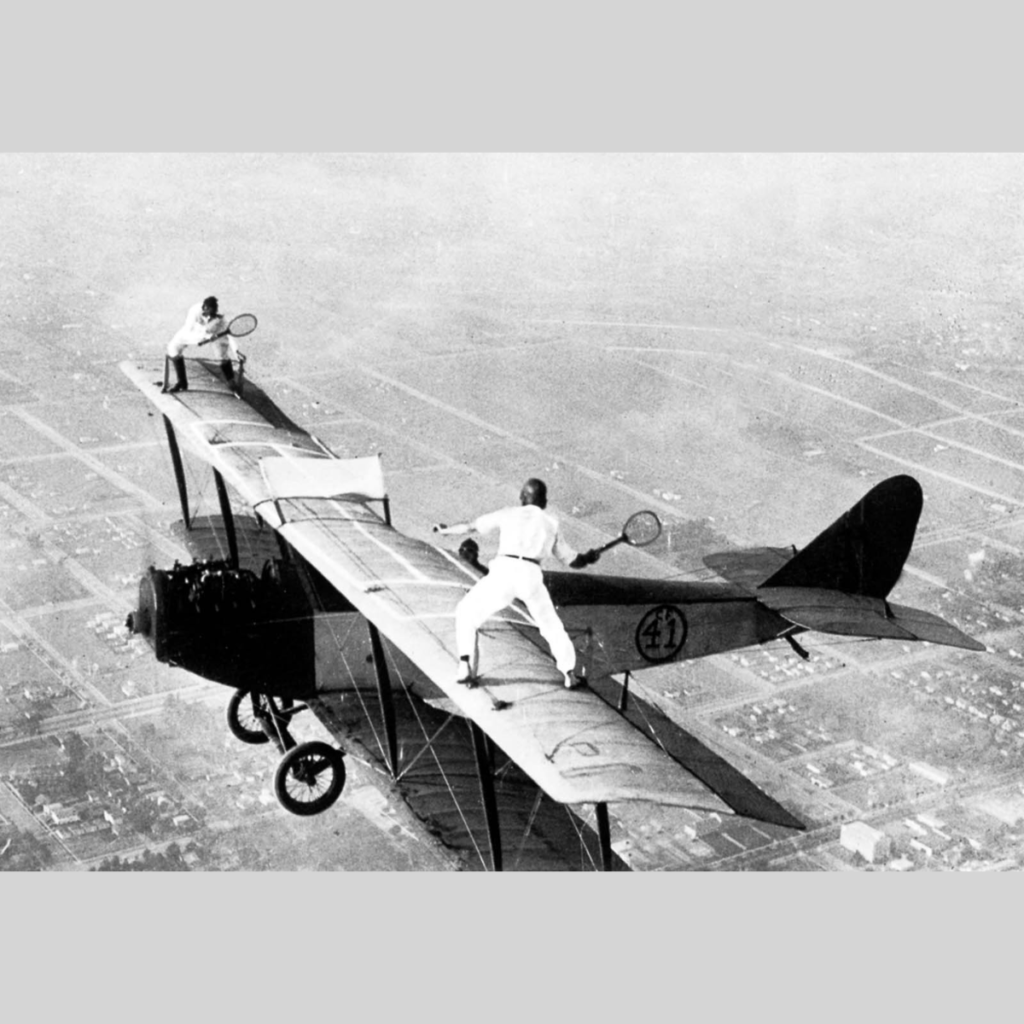

Ivan Unger and Gladys Roy play tennis on top of a biplane. 1925.

Arising as a daredevil stunt in the aerial shows of the 1920s, wing walking was the act of moving along the wings of a biplane during flight.

It started around 1920 at aerial barnstorming shows and originally began as a demonstration of planes’ balance and stability, moved to in-the-air mechanical adjustments and fixes, and then to stunts.

As the stunts became more complicated, these wing performers of the sky would attempt more difficult stunts such as handstands, hanging by one’s teeth, and transferring from one aircraft to another.

The Wing Walkers of old would admit (sometimes proudly) that the point of their acts was to make money on the audience’s prospect of possibly watching someone die.

For the wing-walker him, the experience was actually terrifying. It was tempting just to freeze up and hold on. If you were going to move, you had to be careful to make sure you were holding something substantial enough to take your weight in the face of wind blowing nearly 100 miles per hour.

The “first rule” of wing-walking, according to observers and historians, went something like this: “Don’t let go of what you’ve got until you get hold of something better.”

Richard Schindler practices a stunt. 1919.

An early wing walker who performed daring stunts was 26-year-old American Ormer Locklear, who would walk onto the wings of his plane during training to fix mechanical issues mid-air without having to land.

He would later go on to be one of the first daredevils to perform stunts to the public as part of the aerial show movement of the 1920s. Unfortunately, he would also eventually meet his end during a wing-walking stunt.

Among the many aerialists to become popular were Tiny Broderick, Gladys Ingle, Eddie Angel, Virginia Angel, Mayme Carson, Clyde Pangborn, Lillian Boyer, Jack Shack, Al Wilson, Fronty Nichols, Spider Matlock, Gladys Roy, Ivan Unger, Jessie Woods, Bonnie Rowe, Charles Lindbergh, and Mabel Cody. Eight wing walkers died in a relatively short period during the infancy of wing walking.

Charles Lindbergh, whose career in flight began with wing walking, was well known for stunts involving parachutes. The first African-American woman granted an international pilot license, Bessie Coleman, also engaged in stunts using parachutes.

A wing walker stands on one leg on the wing of a Curtiss ‘Flying Jenny’ biplane in the air above New Jersey. 1920.

Another successful woman in this profession was Lillian Boyer, who performed hundreds of wing-walking exhibitions, automobile-to-plane changes, and parachute jumps.

Eighteen-year-old Elrey Borge Jeppesen, known today for having developed air navigation manuals and charts, joined Tex Rankin’s Flying Circus around 1925; one of his jobs was wing walking.

Not surprisingly there were a few mishaps. Ormer himself became a cropper while working on a film. These wing walk pioneers were operating without a safety net: no parachutes, no safety wires tethering them to the aircraft. A slip of the foot and it was the high dive for our brave showman or showgirl.

In 1938 the authorities in America decided that parachutes had to be worn. The golden age of wing-walking ended in the 1940s, but even today, experienced pilots still perform stunts on restored vintage biplanes.

Wing walkers show off above and below a biplane. 1920.

Famous wing walker Lillian Boyer dangles from the wing of a biplane. 1922.

Lillian Boyer, 1922.

Lillian Boyer hanging from right wing boom using her right hand, circa 1920s.

Gladys Ingle balances atop a biplane. 1926.

Gladys Roy walks the wings of a Curtiss JN-4 ‘Jenny’ biplane over Los Angeles while blindfolded. 1924.

Gladys Ingle, a female wing walker.

Richard Schindler practices a trick on a Klemp plane piloted by Richard Perlia. 1927.

Billy Bomar and Uva Kimmey of the Howard Flying Circus wing-walk on a biplane over New York State. 1930.

Juanita Jover takes a ride strapped to the wings of her boyfriend, stunt pilot Lewis Benjamin’s Tiger Moth biplane. 1962.

Jacqui Cheesman rides the wing of a Tiger Moth biplane at Wycombe Air Park, Buckinghamshire, England. 1968.

Moira Boyd strapped onto the wing of a Tiger Moth biplane at Wycombe Air Park. 1968.

John Kazian mounts the wing of a Stearman Trainer plane flying over Niagara Falls. 1971.

Carol Lynne rides atop a biplane piloted by her husband over Toronto. 1982.