:focal(407x262:408x263)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/42/1b42b470-2382-40ea-90d1-abd3e38b61d6/hh_holmes2.png)

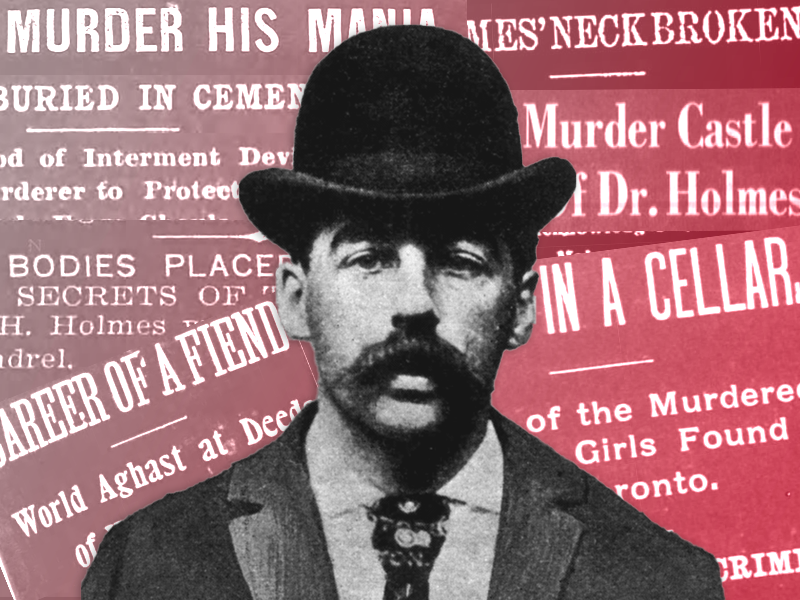

Four days before H.H. Holmes’ execution on May 7, 1896, the Chicago Chronicle published a lengthy diatribe condemning the “multimurderer, bigamist, seducer, resurrectionist, forger, thief and general swindler” as a man “without parallel in the annals of crime.” Among his many misdeeds, the newspaper reported, were suffocating victims in a vault, boiling a man in oil and poisoning wealthy women in order to seize their fortunes.

Holmes claimed to have killed at least 27 people, most of whom he’d lured into a purpose-built “Murder Castle” replete with secret passageways, trapdoors and soundproof torture rooms. According to the Crime Museum, an intricate system of chutes and elevators enabled Holmes to transport his victims’ bodies to the Chicago building’s basement, which was purportedly equipped with a dissecting table, stretching rack and crematory. In the killer’s own words, “I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than a poet can help the inspiration to sing.”

More than a century after his death, Holmes—widely considered the United States’ first known serial killer—continues to loom large in the imagination. Erik Larson’s narrative nonfiction best seller The Devil in the White City introduced him to many Americans in 2003, and a planned adaptation of the book spearheaded by Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese is poised to heighten Holmes’ notoriety even further.

But the true story of Holmes’ crimes, “while horrifying, may not be quite as sordid” as popular narratives suggest, wrote Becky Little for History.com last year. Mired in myth and misconception, the killer’s life has evolved into “a new American tall tale,” argues tour guide and author Adam Selzer in H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil. “[A]nd, like all the best tall tales, it sprang from a kernel of truth.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/98/0098ca83-19a4-4bde-83aa-dbe5e8ee5964/h_h_holmes_castle.jpg)

The facts are these, says Selzer: Though sensationalized reports suggest that Holmes killed upward of 200 people, Selzer could only confirm nine actual victims. Far from being strangers drawn into a house of horrors, the deceased were actually individuals Holmes befriended (or romanced) before murdering them as part of his money-making schemes. And, while historical and contemporary accounts alike tend to characterize the so-called Murder Castle as a hotel, its first and second floors actually housed shops and long-term rentals, respectively.

“When he added a third floor onto his building in 1892, he told people it was going to be a hotel space, but it was never finished or furnished or open to the public,” Selzer added. “The whole idea was just a vehicle to swindle suppliers and investors and insurers.”

As Frank Burgos of PhillyVoice noted in 2017, Holmes was not just a serial killer, but a “serial liar [eager] to encrust his story with legend and lore.” While awaiting execution, Holmes penned an autobiography from prison filled with falsehoods (including declarations of innocence) and exaggerations; newspapers operating at the height of yellow journalism latched onto these claims, embellishing Holmes’ story and setting the stage for decades of obfuscation.

Born Herman Webster Mudgett in May 1861, the future Henry Howard Holmes—a name chosen in honor of detective Sherlock Holmes, according to Janet Maslin of the New York Times—grew up in a wealthy New England family. Verifiable information on his childhood is sparse, but records suggest that he married his first wife, Clara Lovering, at age 17 and enrolled in medical school soon thereafter.

Holmes’ proclivity for criminal activity became readily apparent during his college years. He robbed graves and morgues, stealing cadavers to sell to other medical schools or use in complicated life insurance scams. After graduating from the University of Michigan in 1884, he worked various odd jobs before abandoning his wife and young son to start anew in Chicago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/1e/391eaa3d-c0b5-4559-b9e8-f2f301172cb9/1920px-world_newspaper.jpeg)

Now operating under the name H.H. Holmes, the con artist wed a second woman, Myrta Belknap, and purchased a pharmacy in the city’s Englewood district. Across the street, he constructed the three-story building that would later factor so prominently in tales of his atrocities. Work concluded in time for the May 1893 opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition, a supposed celebration of human ingenuity with distinct colonialist undertones. The fair drew more than 27 million visitors over its six-month run.

To furnish his enormous “castle,” Holmes bought items on credit and hid them whenever creditors came calling. On one occasion, workers from a local furniture company arrived to repossess its property, only to find the building empty.

“The castle had swallowed the furniture as, later, it would swallow human beings,” wrote John Bartlow Martin for Harper’s magazine in 1943. (A janitor bribed by the company eventually revealed that Holmes had moved all of his furnishings into a single room and walled up its door to avoid detection.)

Debonair and preternaturally charismatic, Holmes nevertheless elicited lingering unease among many he encountered. Still, his charm was substantial, enabling him to pull off financial schemes and, for a time, get away with murder. (“Almost without exception, [his victims appeared] to have had two things in common: beauty and money,” according to Harper’s. “They lost both.”) Holmes even wed for a third time, marrying Georgiana Yoke in 1894 without attracting undue suspicion.

As employee C.E. Davis later recalled, “Holmes used to tell me he had a lawyer paid to keep him out of trouble, but it always seemed to me that it was the courteous, audacious rascality of the fellow that pulled him through. … He was the only man in the United States that could do what he did.”

Holmes’ probable first victims were Julia Conner, the wife of a man who worked in his drugstore, and her daughter, Pearl, who were last seen alive just before Christmas 1891. Around that time, according to Larson’s Devil in the White City, Holmes paid a local man to remove the skin from the corpse of an unusually tall woman (Julia stood nearly six feet tall) and articulate her skeleton for sale to a medical school. No visible clues to the deceased’s identity remained.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/e3/f2e354a0-93f2-41ec-85b7-cf868b416db1/screen_shot_2021-05-03_at_125734_pm.png)

Larson recounts Julia’s final moments in vivid detail—but as historian Patrick T. Reardon pointed out for the Chicago Tribune in 2007, the book’s “Notes and Sources” section admits that this novelistic account is simply a “plausible” version of the story woven out of “threads of known detail.”

Other moments in Devil in the White City, like a visit by Holmes and two of his later victims, sisters Minnie and Anna Williams, to Chicago’s meatpacking district, are similarly speculative: Watching the slaughter, writes Larson, “Holmes was unmoved; Minnie and Anna were horrified but also strangely thrilled by the efficiency of the carnage.” The book’s endnotes, however, acknowledge that no record of such a trip exists. Instead, the author says, “It seems likely that Holmes would have brought Minnie and Nannie there.”

These examples are illustrative of the difficulties of cataloguing Holmes’ life and crimes. Writing for Time Out in 2015, Selzer noted that much of the lore associated with the killer stems from 19th-century tabloids, 20th-century pulp novels and Holmes’ memoir, none of which are wholly reliable sources.

That being said, the author pointed out in a 2012 blog post, Holmes was “certainly both … a criminal mastermind [and] a murderous monster.” But, he added, “anyone who wants to study the case should be prepared to learn that much of the story as it’s commonly told is a work of fiction.”

Holmes’ crime spree came to an end in November 1894, when he was arrested in Boston on suspicion of fraud. Authorities initially thought he was simply a “prolific and gifted swindler,” per Stephan Benzkofer of the Chicago Tribune, but they soon uncovered evidence linking Holmes to the murder of a long-time business associate, Benjamin Pitezel, in Philadelphia.

Chillingly, investigators realized that Holmes had also targeted three of Pitezel’s children, keeping them just out of reach of their mother in what was essentially a game of cat and mouse. On a number of occasions, Holmes actually stashed the two in separate lodgings located just a few streets away from each other.

“It was a game for Holmes,” writes Larson. “… He possessed them all and reveled in his possession.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/33/6033a0b6-2912-4c83-8417-844b470f321e/execution_of_h_h_holmes_philadelphia_moyamensing_prison_1896.jpeg)

In July 1895, Philadelphia police detective Frank Geyer found the bodies of two of the girls buried beneath a cellar in Toronto. Given the absence of visible injuries, the coroner theorized that Holmes had locked the sisters in an unusually large trunk and filled it with gas from a lamp valve. Authorities later unearthed the charred remains of a third Pitezel sibling at an Indianapolis cottage once rented by Holmes.

A Philadelphia grand jury found Holmes guilty of Benjamin’s murder on September 12, 1895; just under eight months later, he was executed in front of a crowd at the city’s Moyamensing Prison. At the killer’s request (he was reportedly worried about grave robbers), he was buried ten feet below ground in a cement-filled pine coffin.

The larger-than-life sense of mystery surrounding Holmes persisted long after his execution. Despite strong evidence to the contrary, rumors of his survival circulated until 2017, when, at the request of his descendants, archaeologists exhumed the remains buried in his grave and confirmed their identity through dental records, as NewsWorks reported at the time.

“It’s my belief that probably all those stories about all these visitors to the World’s Fair who were murdered in his quote-unquote ‘Castle’ were just complete sensationalistic fabrication by the yellow press,” Harold Schecter, author of Depraved: The Definitive True Story of H. H. Holmes, Whose Grotesque Crimes Shattered Turn-of-the-Century Chicago, told History.com in 2020. “By the time I reached the end of my book, I kind of realized even a lot of the stuff that I had written was probably exaggerated.”

Holmes for his part, described himself in his memoir as “but a very ordinary man, even below the average in physical strength and mental ability.”