A massive graveyard lies at the edge of an ancient sea. What caused so many horned dinosaurs to perish on the coast?

The story of their demise is now told in stone. Bone Bed 43, in southeastern Alberta, is all that’s left of a herd of Centrosaurus that likely numbered in the thousands. Situated in the roughly 75-million-year-old rock of Dinosaur Provincial Park, the deposit is one of the largest dinosaur graveyards ever uncovered. But it’s hardly the only one. Along the coast of a shallow inland sea that once cut through the belly of North America from northern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, the rocks are brimming with bone beds containing Centrosaurus and other horned dinosaurs.

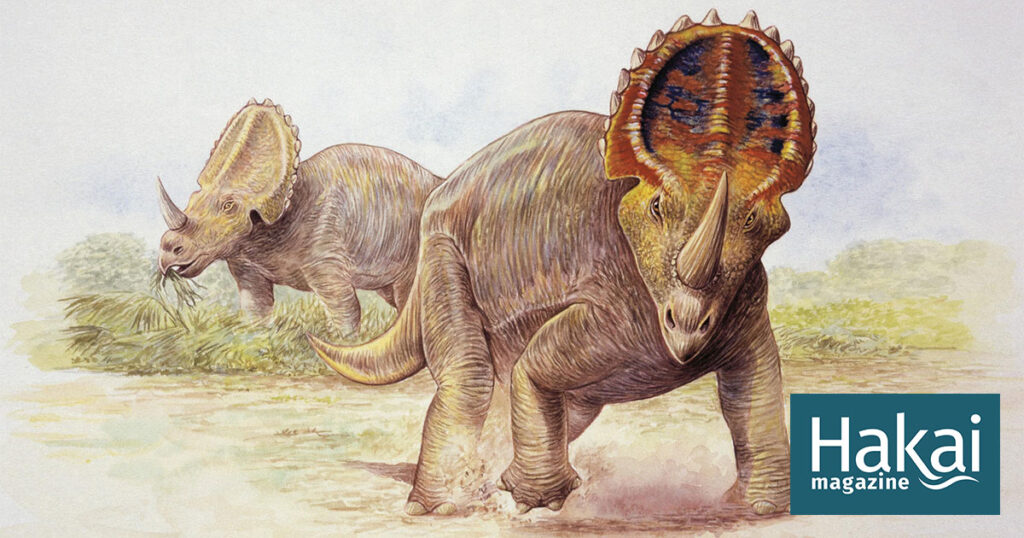

In the time of the dinosaurs’ reign, Alberta was located on the eastern edge of a low-lying subcontinent called Laramidia. Dinosaurs such as Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus, and Wendiceratops—collectively known as ceratopsids—inhabited marshy lowlands that were frequently inundated with severe storms that traveled up the coast. Heavy rains caused river channels to swell and overflow, creating a record of both the ancient storms and the dinosaurs that got caught in them, says Royal Saskatchewan Museum paleontologist Emily Bamforth. What’s puzzled paleontologists, however, is why the horned dinosaurs that thrived in the lowlands seemed so vulnerable to rising waters.

Perhaps the dinosaurs’ flashy skulls had something to do with it. Since their origin around 90 million years ago, ceratopsids had evolved large, garish frills decked out in all manner of spikes and hooks, not to mention accessory horns on the cheeks, nose, and eyebrows. The result of all this adornment? These animals were top-heavy. By running computer simulations to calculate the dinosaurs’ center of gravity, Donald Henderson, a paleontologist at Alberta’s Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, found that the heavy skulls of Centrosaurus and other horned dinosaurs made it difficult for them to keep their heads above water. Duckbilled dinosaurs known as hadrosaurs, by contrast, were more evenly balanced, and had adapted to aquatic living in ways that the landlubbing ceratopsids hadn’t.

“Ceratopsids could not have held their heads as high off the ground as a hadrosaur could,” adds Michael J. Ryan, a paleontologist at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in Ohio. But it’s also worth noting, Ryan says, that horned dinosaurs were much more common along the coasts than hadrosaurs were.

Untangling the nature of these coastal lowlands is an ongoing paleontological effort. There was something about these habitats that lured the dinosaurs to the coast, notes Ryan—the vegetation, perhaps, or the moist soil, which would have incubated soft eggs. But whatever drew them there also left them at the mercy of the storms.

Nevertheless, ceratopsids thrived in this environment for millions of years, suggesting that some of them, at least, managed to keep their chins up.