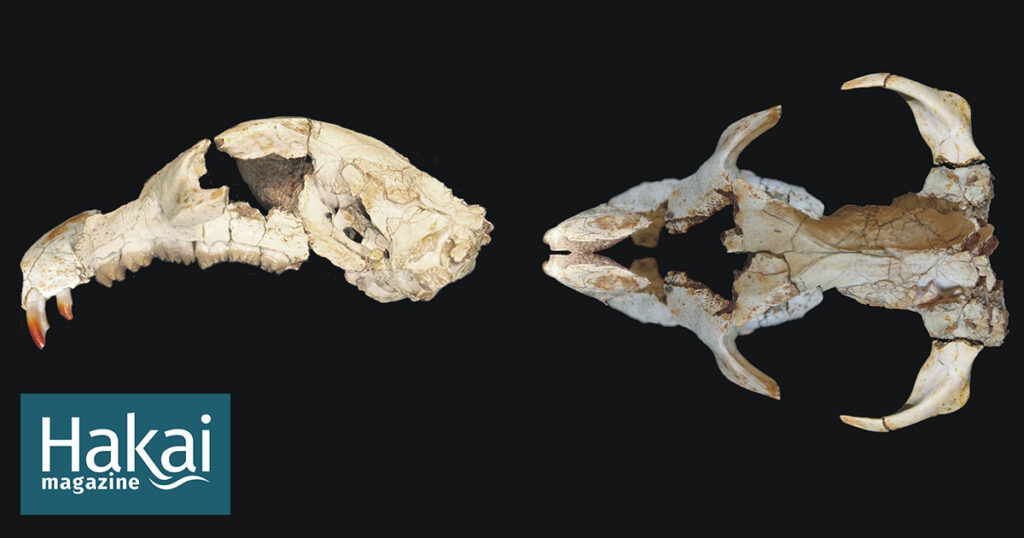

Scientists know about this Cretaceous critter thanks to a partial skeleton unveiled earlier this year by Zoltán Csiki-Sava, a paleontologist at the University of Bucharest in Romania, and his colleagues. The researchers described the species as Litovoi tholocephalos—meaning dome-skulled ruler.

Litovoi’s importance to evolutionary history wasn’t immediately apparent, Csiki-Sava says. When the fossilized mammal was discovered in Romania’s Haţeg Basin in 2014, it seemed to be another example of an archaic type of rodent-like mammal called a multituberculate. The find was interesting because mammals are extremely rare in rocks this old, but at the same time, other multituberculates had already been found in the same deposit. Yet when Csiki-Sava and his colleagues examined the skull more closely using a CT scan, “we came to understand this specimen has more to offer than simply being well preserved,” he says.

What made Litovoi stand out was its braincase, which was much smaller than it should have been for its body size. This feature, along with the fact that Litovoi has not been found anywhere else, hints that this little mammal was an ancient beneficiary of an evolutionary phenomenon known as the island effect, the island rule, or Foster’s Rule after biologist J. Bristol Foster who coined the concept in 1964.

During the late Cretaceous period, the Haţeg Basin in western Romania was largely submerged beneath an ancient sea. Illustration by Mark Garrison

As a scientific hypothesis, the basic definition of the island effect goes like this: islands are isolated areas that often result in unique evolutionary changes in the species that live on them. On islands, animals are often smaller than their mainland counterparts, adapted to their restricted space. The island of Flores in Indonesia, for example, is famous for once being home to pint-sized elephants and small prehistoric humans popularly known as Hobbits.

But the island effect also goes the other way, and typically small animals—usually free from the ravages of large predators—become huge. Between five and three million years ago, for instance, an enormous rabbit named Nuralagus rex lived on the Spanish island of Menorca.

Back in the time of Litovoi, what we now know as Romania was inundated by the sea. Small islands provided refuge to dinosaurs and other terrestrial species. Isolated, these species’ evolutionary pathways took some strange turns.

Litovoi’s disproportionately tiny brain, Csiki-Sava says, seems to be another example of the island effect.

“Brain reduction associated with island habitat was documented previously in hippos, goats, and even hominids,” he says. Brains use a lot of energy, so small ones are advantageous on islands where resources are often limited.

The discovery fits in with other animal species unearthed in Romania that also show the evolutionary signs of island life. Some dinosaurs from Cretaceous Romania, for instance, are dwarfed. Magyarosaurus, a long-necked, herbivorous titanosaur is one such species. Befitting the name, the largest titanosaurs grew as long as a blue whale. Romania’s shrunken Magyarosaurus was no bigger than a cow.

Stranger still is Balaur bondoc. This carnivore is similar in size to its more famous cousin Velociraptor, but only has two fingers on each hand instead of three and a double set of hyper-extendable killing claws instead of the standard one.

Balaur bondoc, a relative of the famous dinosaur Velociraptor, has odd adaptations as a result of its isolation. Photo by Stocktrek Images, Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

If Litovoi’s tiny brain is a result of the island effect, then it’s a particularly important find. Csiki-Sava says that if it is, then the discovery pushes back the timeline of the first documented case of the island effect in mammals. It also shows that reducing in brain size, without a simultaneous reducing body size, is another way evolution might drive animals to respond to island life.

Litovoi’s unique adaptations highlight something else. Mammals in the age of dinosaurs are often characterized as small, shrewlike insectivores that hid in the night until the reptilian reign of terror ended 66 million years ago. But a vast accumulation of fossils over the past few decades has added nuance to this narrative. It’s fair to say that mammals did stay relatively small during the heyday of the dinosaurs, but they diversified into a variety of forms—from the prehistoric equivalents of raccoons and aardvarks, to mammal cousins that lived like beavers and flying squirrels.

Multituberculates such as Litovoi are part of that story. Oklahoma State University paleontologist Anne Weil dubs them “the most successful order of mammals to have lived, so far.”

Multituberculates flourished during the Mesozoic, evolving into species of a variety of sizes and occupying environments from forests to deserts. “Litovoi is further evidence of the kinds of specialization they were capable of,” Weil says. Mammalian expression showed that even in the era of dinosaur dominance, size wasn’t everything.