It’s 1918 and France was caught in the final year of World War I.

American photographer Lewis Hine traveled across the country for the American Red Cross, documenting their work with refugees, orphans, and wounded soldiers. Lost for decades, his poignant work has recently been made public by the Library of Congress.

Lewis Hine has been acknowledged as one of America’s principal 20th-century photographers, best known for his moving portraits of immigrants on Ellis Island, child laborers in factories and mines, and steelworkers balanced on high girders of the Empire State Building.

In World War I, Hine became a photographer for the Red Cross, assigned to record the devastation in Europe and document the need for relief work.

In the spring and summer of 1918, he photographed hundreds of war refugees, orphaned children, hospitalized U.S. soldiers, nurses, and volunteers, as well as the country’s ruins.

Original caption: “Jeanne Septvents is a beautiful French girl, 10 years old, whose father, for nearly a year a prisoner in Germany, has given his life for France. Jeanne has been adopted by Company ‘E,’ 6th Battalion of the 20th Engineers. When the American Red Cross photographer found her in the garden of her little stone house at Caen, she was playing with knuckle-bones that she had painted red, white, and blue in honor of her godfathers. She wrote them soon after she was adopted saying: ‘I hope you are all in good health and not too unhappy at the front and I send big kisses to you all.’ September, 1918.”

The photographs were intended to drum up support for the Red Cross and appeal to an American audience.

Some of these pictures appeared in Red Cross publications, but most of them went into the organization’s archives, where they remained hidden for almost 100 years.

At the end of World War II, the Red Cross deposited its photograph collection — some 50,000 images — at the Library of Congress, where Hine’s work was ”lost” due to an eccentric filing code that baffled historians for nearly 40 years.

Author Daile Kaplan was finally able to break the code, identify Hine’s photographs, and reintroduce to the world the best of this master’s “lost” photographs, giving him his due, at last, as a true pioneer of photojournalism.

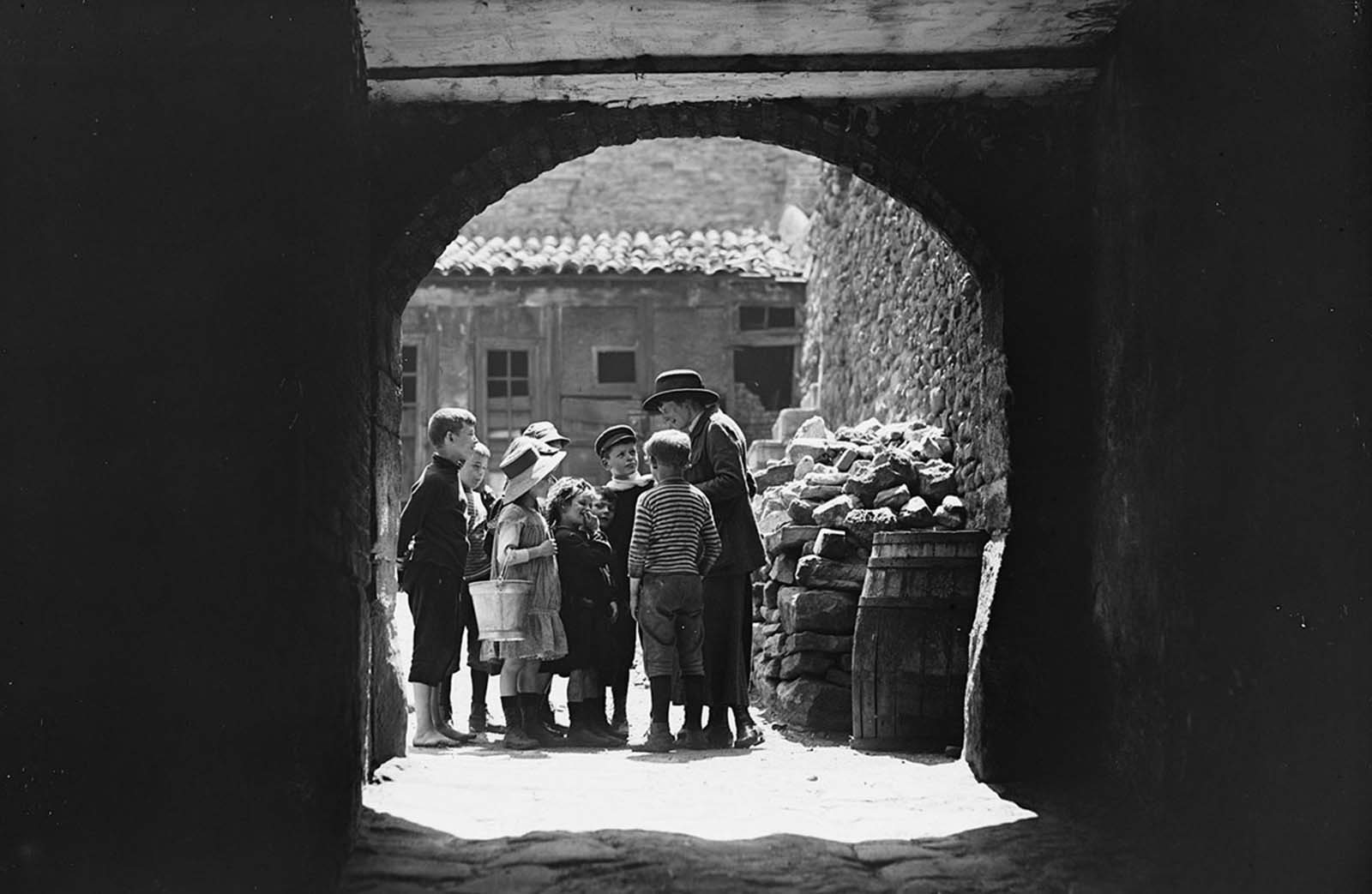

Original caption: “Group of refugee children who have been received by a French organization, aided by the American Red Cross at St. Sulpice, Paris. They are about to start for Grand Val, the country home which has been opened for them on a large estate near Paris, where an outdoor life will build up their health. August, 1918.”

An overview of war-damaged Lens, France, on April 11, 1919.

Parcels bound for the front line, at an American Red Cross facility in Paris in July of 1918.

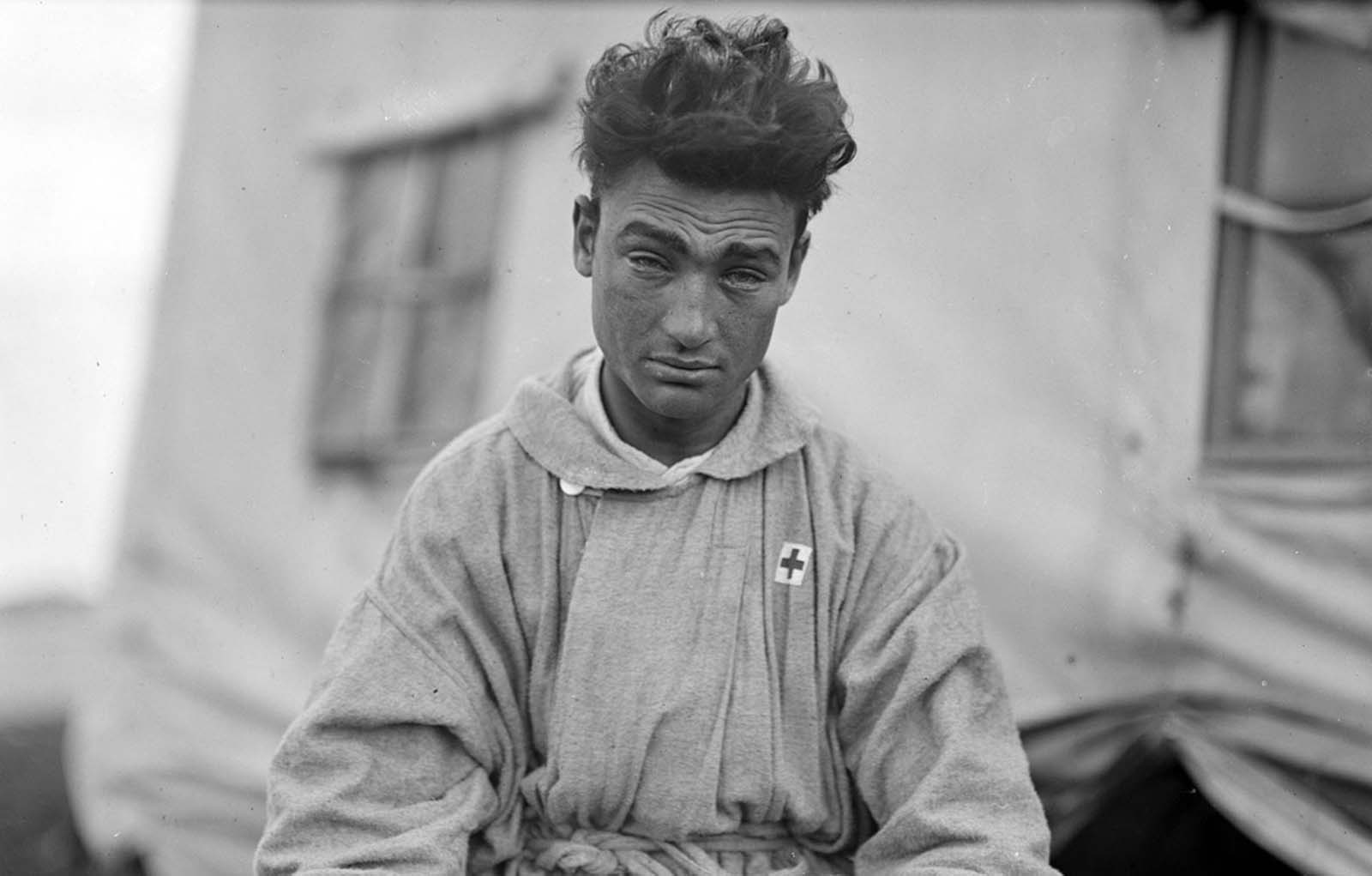

Original caption: “Trudeau Sanitarium, Hachette, near Paris. Rene drove cattle for the Germans for over two years. He still walks in his sleep and dreams he is being shot, etc. Rene is a little repatrie who is getting strong at Trudeau Sanitarium. The manor house of Hachette is an American Red Cross hospital for tubercular women. On the grounds, nearby barracks have been built, where about 180 children are housed, each for a period of three months or more. They are under-nourished children of tubercular tendencies, many of whom have tubercular parents. September, 1918.”

American troops march through Place de Jena and down Avenue du President Wilson in Paris on July 4, 1918.

A crowd gathers in the Place de la Concorde, Paris, on July 4th, 1918, to see the American troops march in the parade to celebrate American Independence Day.

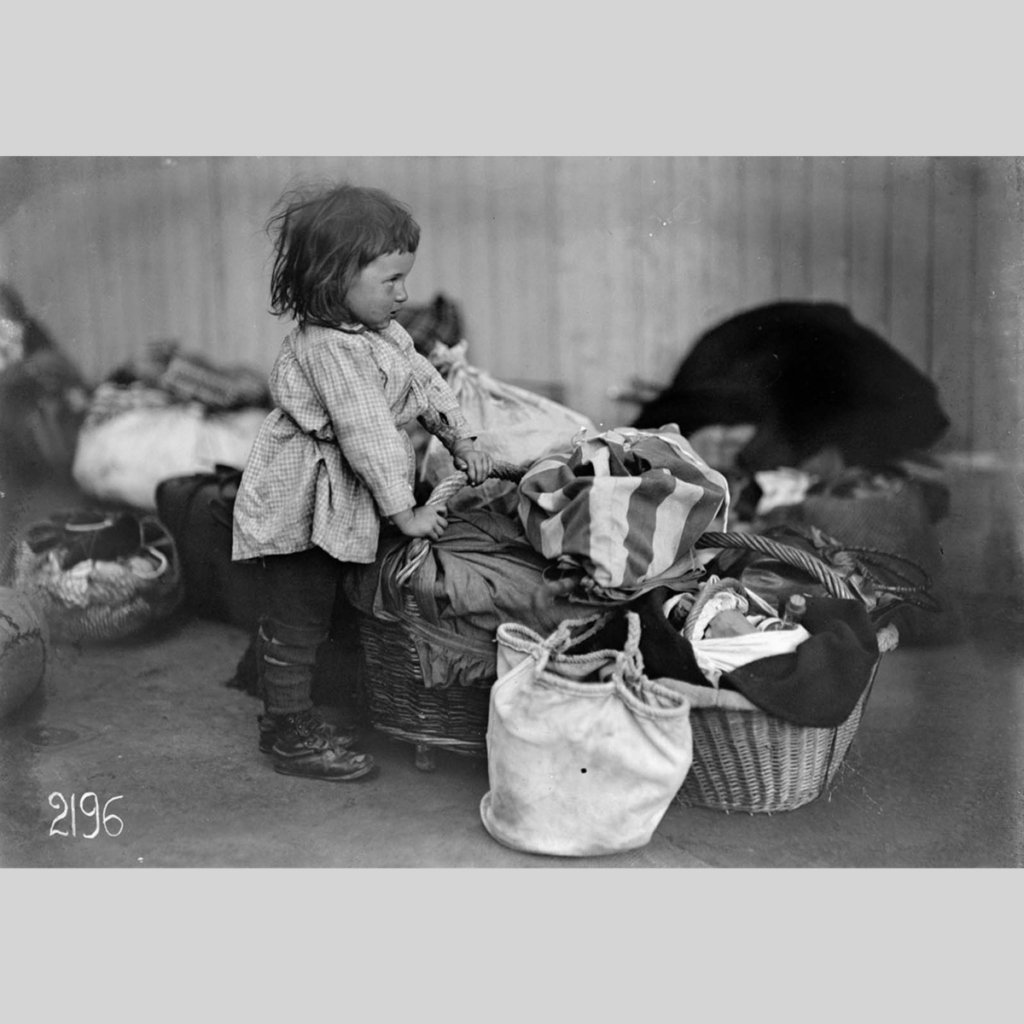

Original caption: “Not merely a fair-weather friend, this little refugee clings to her dog through thick and thin. Driven from their home by the invaders, she and her parents came to the Seminary of St. Sulpice, Paris, where all refugees are received and—with aid from the American Red Cross—are fed, cared for, and helped on their way. She is waiting for the American Red Cross “camion” to take her to the station, where the journey will be resumed. June 8, 1918.”

Original caption: “Chauffeurs of the American Fund for French Wounded. They had assisted the Red Cross by driving cars for the Children’s Bureau, but are now attached to the Service de Sante, under the French Government. From left to right they are: Miss Rogers, Miss Hughes, Miss Robeson, Miss Caspari, Mrs. Crean, Miss Kennerley, Miss Wilde, and Miss Washburn. September, 1918.”

Cars of American Red Cross Transportation Department, set up for inspection by Majors Perkins and Osborne on July 7, 1918.

This French woman, forced by the Germans to leave her home, was able to save only a suitcase full of clothes and her two pet roosters, which she is happily feeding in front of the American Red Cross Refugee Hut at the Gare du Nord, Paris, on June 27, 1918.

Original caption: “At the Gare de Lyons, Paris. This little refugee stands manfully on the job of taking care of the family baggage until his parents come back. All refugees arriving at this station from the invaded districts are fed and cared for by the Bon Accueuil, a French relief organization, aided by the American Red Cross. June, 1918.”

A visitor from the Red Cross Bureau of Refugees inquires into the needs of children in the tenements, in which refugees are housed, on July 16, 1918.

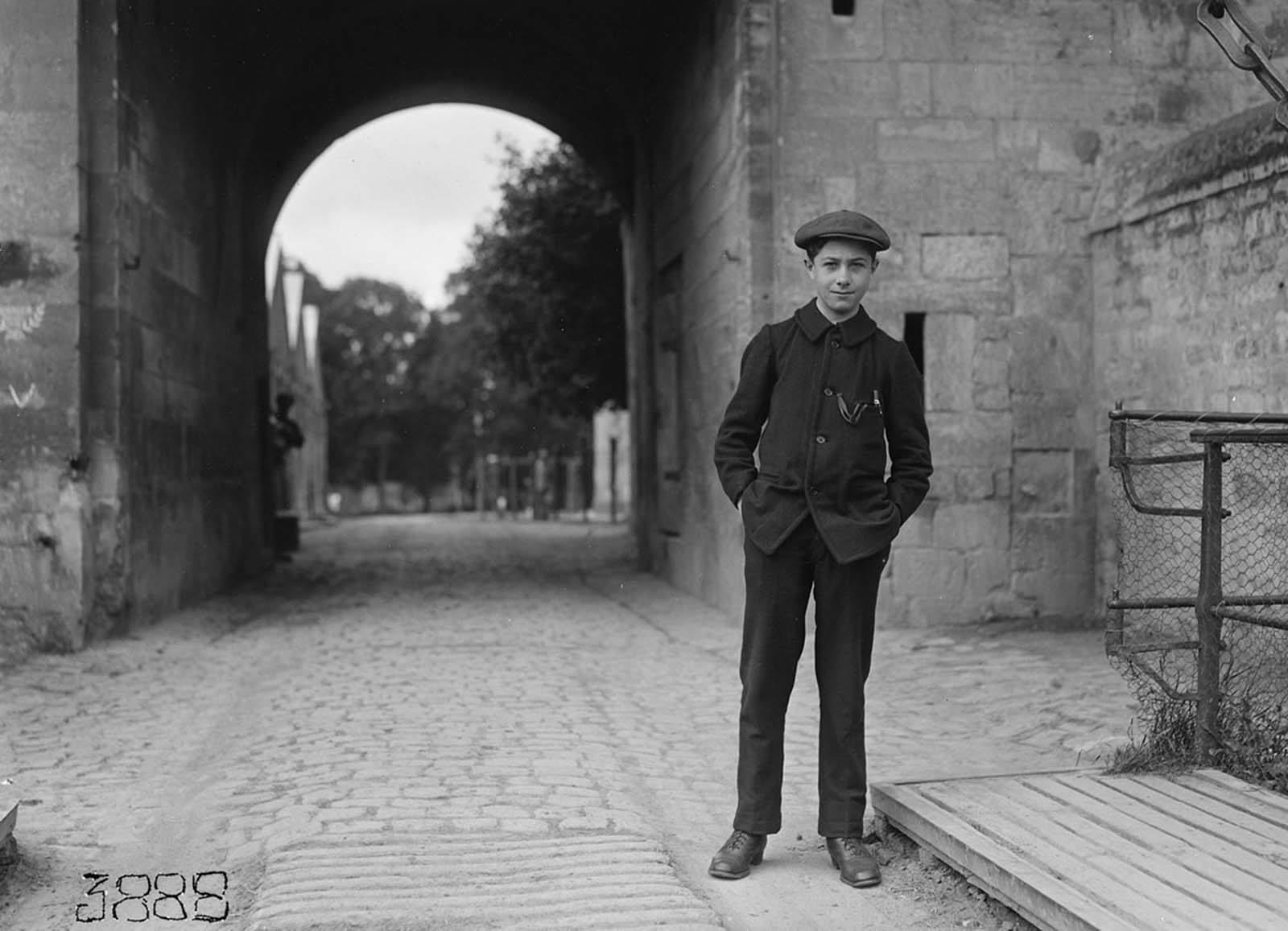

Original caption: “Andre Petit lives in one room in a busy street in Caen with his mother and his two brothers. Andre’s ‘Dear godfathers,’ Co. C. of the 504th Engineers, sent him some money ‘for a game.’ He bought some Boche soldiers ‘so that he could be the American soldier to kill them all.’ August, 1918.”

Original caption: “Refugees from Lorraine sing Marseilles as they cross the drawbridge of the old Chateau of Caen. In the enclosure of the Chateau, barracks have been provided for 160 children to live in under the direction of the Prefet Mirman. Among them are 15 ‘Stars and Stripes’ children, French wards of American soldiers. August, 1918.”

St. Sulpice, Secours de Guerre. Refugee children living here playing as Red Cross nurses in August of 1918.

Original caption: “Roger Lang is only 14 years old but even so, he wants to fight for France, and he wants to avenge his mother who died from fright one night during a bombardment, and his father who went to the front in 1914 and has never come back. The boy has been adopted by the 101st Machine Gun Battalion. Thanks to the money which they have sent him, he will go to a trade school and then he will be able to support his little brother Pierre. For the war will surely be over before Roger’s class is called, and then he and Pierre can go back to Lorraine, which is their home even if their house is destroyed and even if the father and mother are both gone. August, 1918.”

Meal time at La Jonchere, one of the colonies established by the Comite Franco-Americain pour la Protection des Enfants de la Frontiere, which, with aid from the American Red Cross, provides a home and education for about 1,500 children made destitute by the war. July, 1918.

Original caption: “Two months ago, little Gilberte Dieu and her mother left their home in the Somme to go see the soldier father who was in a hospital, badly gassed. When they reached the town where he was, they learned that the Germans were approaching their home, and if they wished to save any of their possessions they must hurry back. They started home, only to find they were too late. Again they turned around to go back to the hospital, hoping to find the father better, and learned that he was dead. Now they are living in a quiet old town in Normandy. Gilberte is as pale as if she had been ill a long time, but she has been adopted by Company E of the 406th Telegraph Battalion, and the money they have sent will provide her generously with good food and warm clothing for next winter. Perhaps with these, the memory of what the war has done to her will fade out partly from her tragic little face. September, 1918.”

A boy puts on his new shoes at Trudeau Sanitarium, Hachette, near Paris in September of 1918.

Original caption: “Cantigny, France, April 14, 1919. Site of the former village of Cantigny, not far from Montdidier. The German advance was stopped at this point; American troops engaged in heavy fighting at Cantigny.”

Original caption: “Lens, France, April 11, 1919. Man and wife, living in cellar of their former home, which is in complete ruins. They were in Lens for 30 months during the German occupation, and were repatriated thru Switzerland and by way of Evian, in January of 1917. The wife remained in southern France some months after repatriation. They have now been three weeks in Lens, and plan to keep their present quarters in the cellar for an indefinite period of time.”

The Eiffel Tower and a replica of the Statue of Liberty on Île aux Cygnes in Paris in March of 1919.

Original caption: “Unloading wounded Americans from the trucks which brought them from the hospitals to the famous Parisian cafe ‘Les Ambassadeurs,’ where the American Red Cross gave them an entertainment on the 4th of July afternoon in 1918.”

Original caption: “Sun treatment for bad wounds, Hospital #5. Wounded American soldiers taking the sun cure at American Military Hospital No. 5 at Auteuil, which is supported by the American Red Cross. In this treatment, the wound is exposed and unbandaged to the full sunshine with only the protection of a mosquito netting stretched above it to protect from insects, etc. September, 1918.”

Original caption: “Types of many races fighting in the American army. This man is from Austria. Picture taken at the American Red Cross hospital at Auteuil. October, 1918.”

Original caption: “Types of many races fighting in the American army. A Carolina negro. Picture taken at the American Red Cross hospital at Auteuil. October, 1918.”

Nurses line up after a fire drill at 60 Rue St. Didier in Paris, where the American Red Cross makes “front parcels,” in August of 1918.

Original caption: “Shell-shock patients having a happy time fishing under the wall of the old chateau. Under the walls of the old chateau these Americans are recovering from war-neurosis, as the scientists now call the condition that used to be described as ‘shell-shock.’ Capt. A.E. Dennis, Red Cross hospital representative for the U.S. Army at Blois, has obtained wonderful results by taking a number of these patients away from the noise and congestion of the hospital to a quiet outdoor life in the forest of the Chateau Chambord near Blois. September, 1918.”

Original caption: “The usual afternoon rush when Red Cross Lady and Capt. Sterling S. Beardsley arrive to distribute chocolate. Base Hospital St-Denis. September, 1918.”

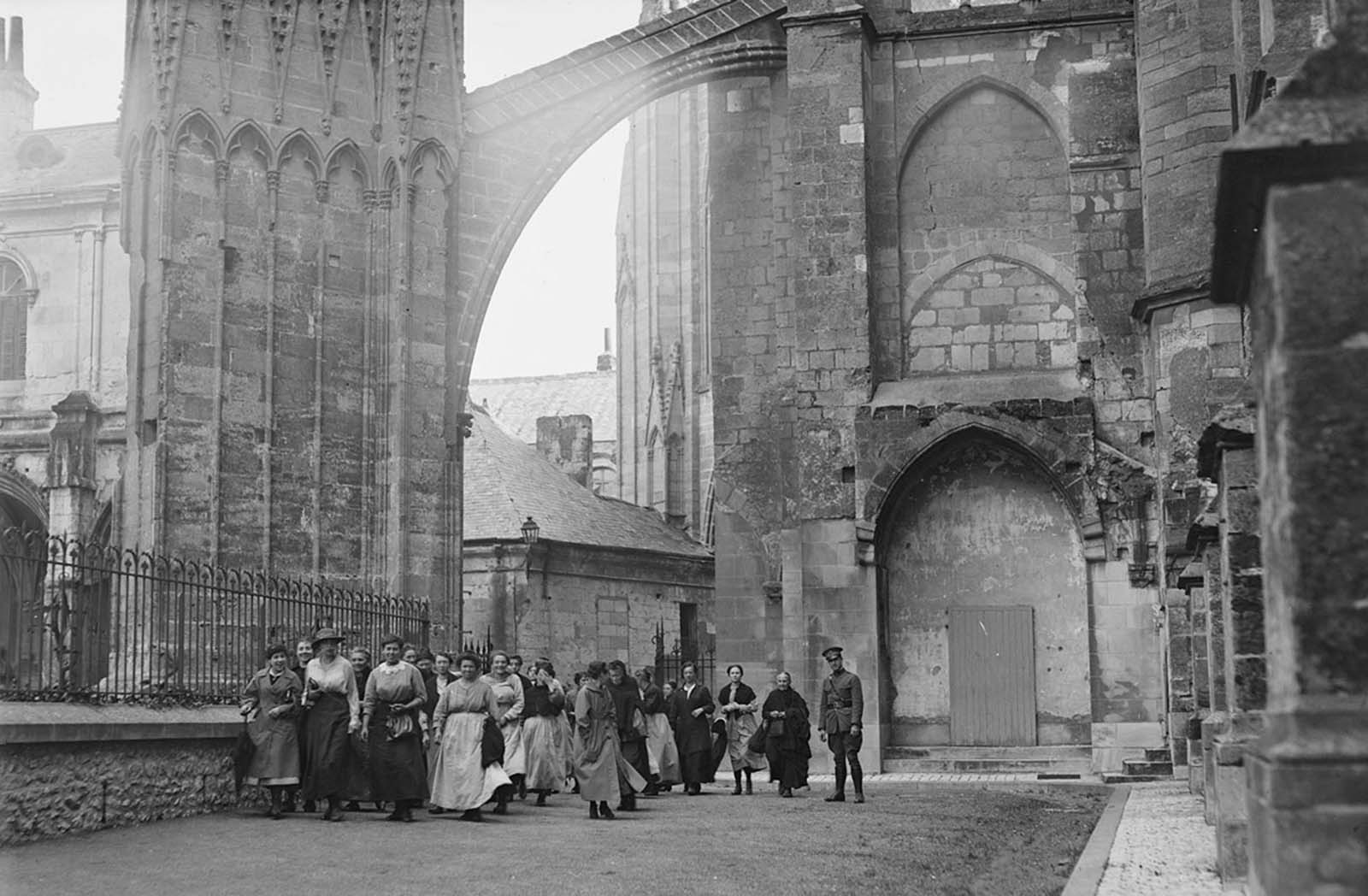

Original caption: “This is where the socks are mended. Bureau of refugees, Tours. In an old monastery building adjacent to the Great Cathedral at Tours, a group of refugee women under the auspices of the Red Cross are coming to their work of mending socks for the American soldiers. This is part of the great salvage work—that is, making socks, sweaters, etc. that have been worn as good as new, while at the same time the women are enabled to support themselves. In this one group, a quarter of a million socks and 150,000 other garments have been mended in two months and nearly 70,000 francs have been earned by the women. Their earnings average five to six francs a day. September, 1918.”

Mending socks for the American soldiers, Bureau of Refugees, Tours, September of 1918.

Original caption: “One of the colored troops entertaining a group of soldiers (white and colored) in the American Red Cross Recreation Hut at Orleans. September, 1918.”

Original caption: “Paris. The American Red Cross man took this ‘doughboy’ to see the wonders of Notre Dame. He climbed high up in one of the towers where he is shown addressing this fine stone bird, ‘You ain’t the American eagle.’ March, 1919.”